Video - Guns, Germs and Steel

|

Extract from Jared Diamond – Guns, Germs and Steel

Why, within Eurasia, were European societies, rather than those of the Fertile Crescent or China or India, the ones that colonized America and Australia, took the lead in technology, and became politically and economically dominant in the modern world? Why did China also lose its lead? Its falling behind is initially surprising, because China enjoyed undoubted advantages: a rise of food production nearly as early as in the Fertile Crescent; ecological diversity from North to South China and from the coast to the high mountains of the Tibetan plateau, giving rise to a diverse set of crops, animals, and technology; a large and productive expanse, nourishing the largest regional human population in the world; and an environment less dry or ecologically fragile than the Fertile Crescent's, allowing China still to support productive intensive agriculture after nearly 10,000 years, though its environmental problems are increasing today and are more serious than western Europe's. Why didn't Chinese ships proceed around Africa's southern cape westward and colonize Europe, before Vasco da Gama's own three puny ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope eastward and launched Europe's colonization of East Asia? |

|

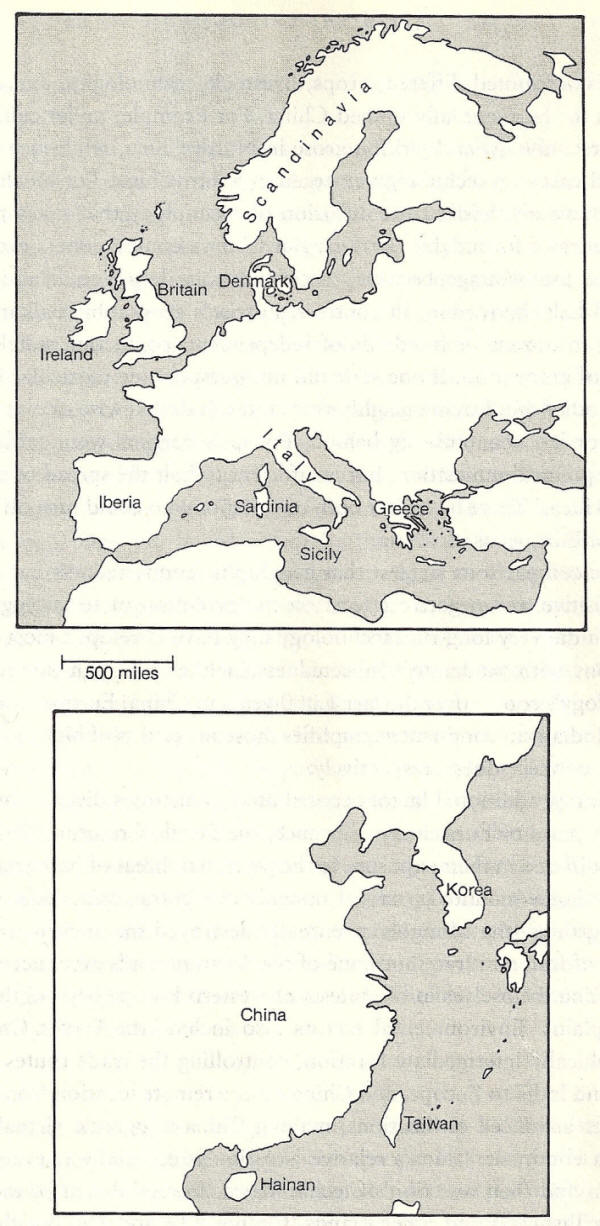

The answer is again suggested by maps. Europe has a highly indented coastline, with five large peninsulas that approach islands in their isolation, and all of which evolved independent languages, ethnic groups, and governments: Greece, Italy, Iberia, Denmark, and Norway / Sweden. China's coastline is much smoother, and only the nearby Korean Peninsula attained separate importance. Europe has two islands (Britain and Ireland) sufficiently big to assert their political independence and to maintain their own languages and ethnicities, and one of them (Britain) big and close enough to become a major independent European power. But even China's two largest islands, Taiwan and Hainan, have each less than half the area of Ireland; neither was a major independent power until Taiwan's emergence in recent decades; and Japan's geographic isolation kept it until recently much more isolated politically from the Asian mainland than Britain has been from mainland Europe. Europe is carved up into independent linguistic, ethnic, and political units by high mountains (the Alps, Pyrenees, Carpathians, and Norwegian border mountains), while China's mountains east of the Tibetan plateau are much less formidable barriers.

China's heartland is bound together from east to west by two long navigable river systems in rich alluvial valleys (the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers), and it is joined from north to south by relatively easy connections between these two river systems (eventually linked by canals). As a result, China very early became dominated by two huge geographic core areas of high productivity, themselves only weakly separated from each other and eventually fused into a single core. Europe's two biggest rivers, the Rhine and Danube, are smaller and connect much less of Europe. Unlike China, Europe has many scattered small core areas, none big enough to dominate the others for long, and each the center of chronically independent states. Once China was finally unified, in 221 B.C., no other independent state ever had a chance of arising and persisting for long in China. Although periods of disunity returned several times after 221 B.C., they always ended in reunification. But the unification of Europe has resisted the efforts of such determined conquerors as Charlemagne, Napoleon, and Hitler; even the Roman Empire at its peak never controlled more than half of Europe's area. |

Thus, geographic connectedness and only modest internal barriers gave China an initial advantage. North China, South China, the coast, and the interior contributed different crops, livestock, technologies, and cultural features to the eventually unified China. For example, millet cultivation, bronze technology, and writing arose in North China, while rice cultivation and cast-iron technology emerged in South China. For much of this book I have emphasized the diffusion of technology that takes place in the absence of formidable barriers. But China's connectedness eventually became a disadvantage, because a decision by one despot could and repeatedly did halt innovation. In contrast, Europe's geographic balkanization resulted in dozens or hundreds of independent, competing statelets and centres of innovation. If one state did not pursue some particular innovation, another did, forcing neighbouring states to do likewise or else be conquered or left economically behind. Europe's barriers were sufficient to prevent political unification, but insufficient to halt the spread of technology and ideas. There has never been one despot who could turn off the tap for all of Europe, as of China.

These comparisons suggest that geographic connectedness has exerted both positive and negative effects on the evolution of technology. As a result, in the very long run, technology may have developed most rapidly in regions with moderate connectedness, neither too high nor too low. Technology's course over the last 1,000 years in China, Europe, and possibly the Indian subcontinent exemplifies those net effects of high, moderate, and low connectedness, respectively. Naturally, additional factors contributed to history's diverse courses in different parts of Eurasia. For instance, the Fertile Crescent, China, and Europe differed in their exposure to the perennial threat of barbarian invasions by horse-mounted pastoral nomads of Central Asia. One of those nomad groups (the Mongols) eventually destroyed the ancient irrigation systems of Iran and Iraq, but none of the Asian nomads ever succeeded in establishing themselves in the forests of western Europe beyond the Hungarian plains. Environmental factors also include the Fertile Crescent's geographically intermediate location, controlling the trade routes linking China and India to Europe, and China's more remote location from Eurasia's other advanced civilizations, making China a gigantic virtual island within a continent. China's relative isolation is especially relevant to its adoption and then rejection of technologies, so reminiscent of the rejections on Tasmania and other islands . But this brief discussion may at least indicate the relevance of environmental factors to smaller-scale and shorter-term patterns of history, as well as to history's broadest pattern.

These comparisons suggest that geographic connectedness has exerted both positive and negative effects on the evolution of technology. As a result, in the very long run, technology may have developed most rapidly in regions with moderate connectedness, neither too high nor too low. Technology's course over the last 1,000 years in China, Europe, and possibly the Indian subcontinent exemplifies those net effects of high, moderate, and low connectedness, respectively. Naturally, additional factors contributed to history's diverse courses in different parts of Eurasia. For instance, the Fertile Crescent, China, and Europe differed in their exposure to the perennial threat of barbarian invasions by horse-mounted pastoral nomads of Central Asia. One of those nomad groups (the Mongols) eventually destroyed the ancient irrigation systems of Iran and Iraq, but none of the Asian nomads ever succeeded in establishing themselves in the forests of western Europe beyond the Hungarian plains. Environmental factors also include the Fertile Crescent's geographically intermediate location, controlling the trade routes linking China and India to Europe, and China's more remote location from Eurasia's other advanced civilizations, making China a gigantic virtual island within a continent. China's relative isolation is especially relevant to its adoption and then rejection of technologies, so reminiscent of the rejections on Tasmania and other islands . But this brief discussion may at least indicate the relevance of environmental factors to smaller-scale and shorter-term patterns of history, as well as to history's broadest pattern.