Lesson 4 - The transport revolutions

This economic feature of the industrial revolution deserves a section to itself.

This economic feature of the industrial revolution deserves a section to itself.

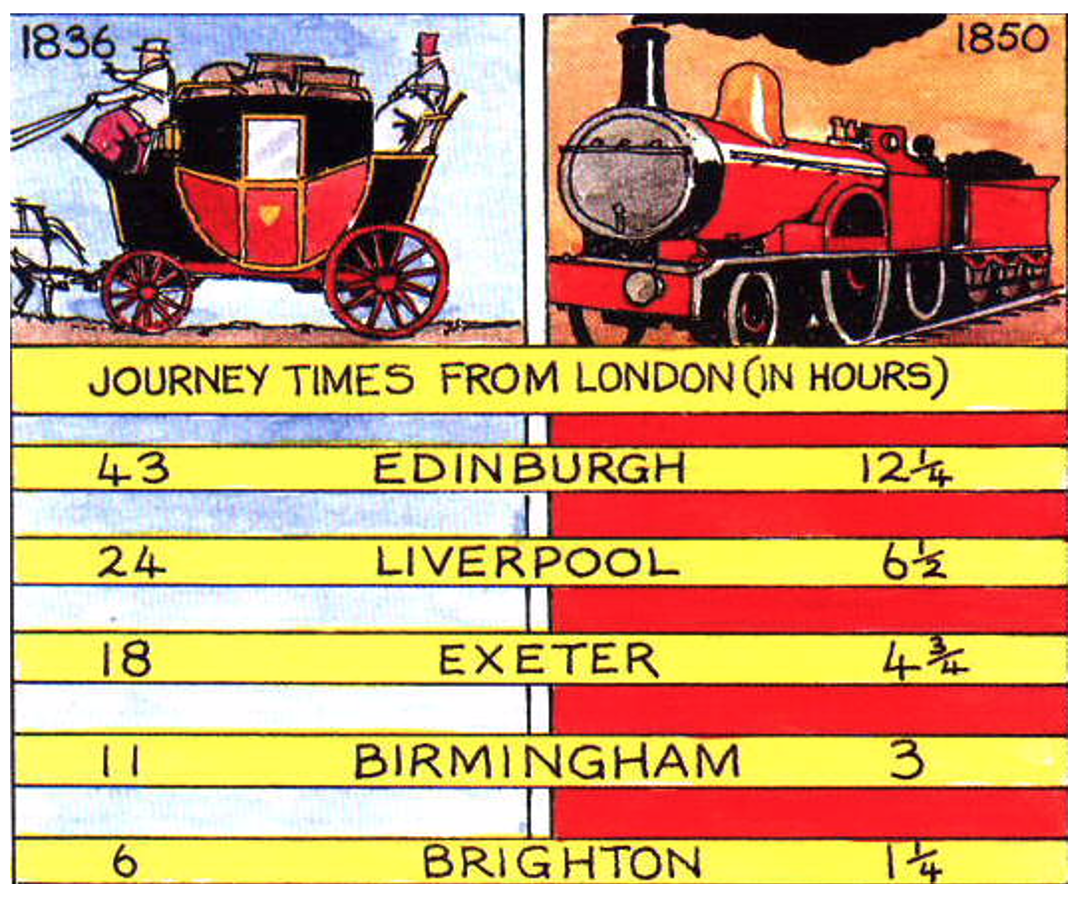

The first transport revolution dating from 1750 and lasting until 1830 concerned improvements in roads and in particular the building of canals. The second beginning in 1800 and lasting until the second half of the 19th century concerned the development of steam locomotives and the railways.

|

The road network in Britain in 1700 was considerably worse than in Roman times.

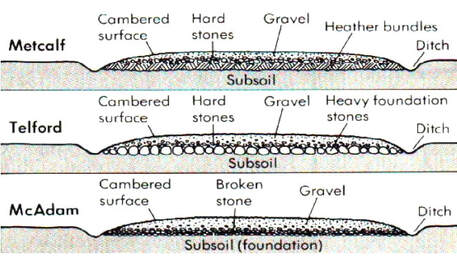

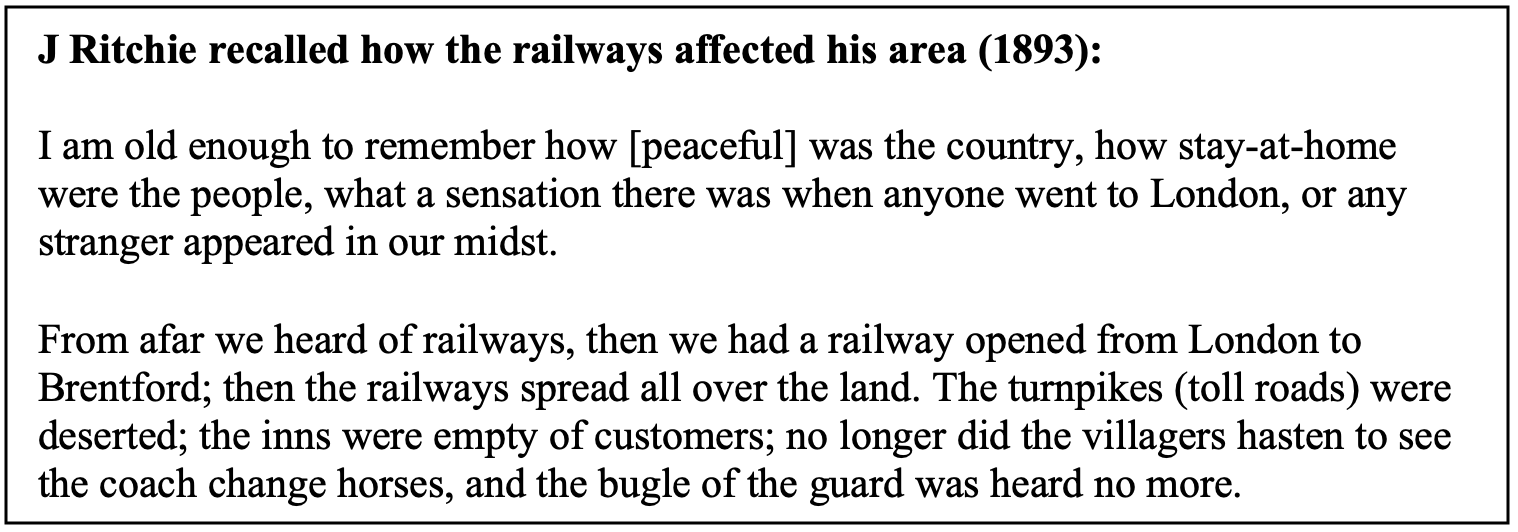

In 1706 government introduced the Turnpike Trust law which allowed private citizens to improve and maintain roads and then charge tolls. Some of Britain's most important engineers such as Telford and McAdam worked to improve road quality. Turnpike roads were very unpopular but they did lead to improvements and a boom in the growth and importance of stage coach companies. By 1837 there were 3,300 stage coaches employing 30,000 people and hundreds of inns. |

|

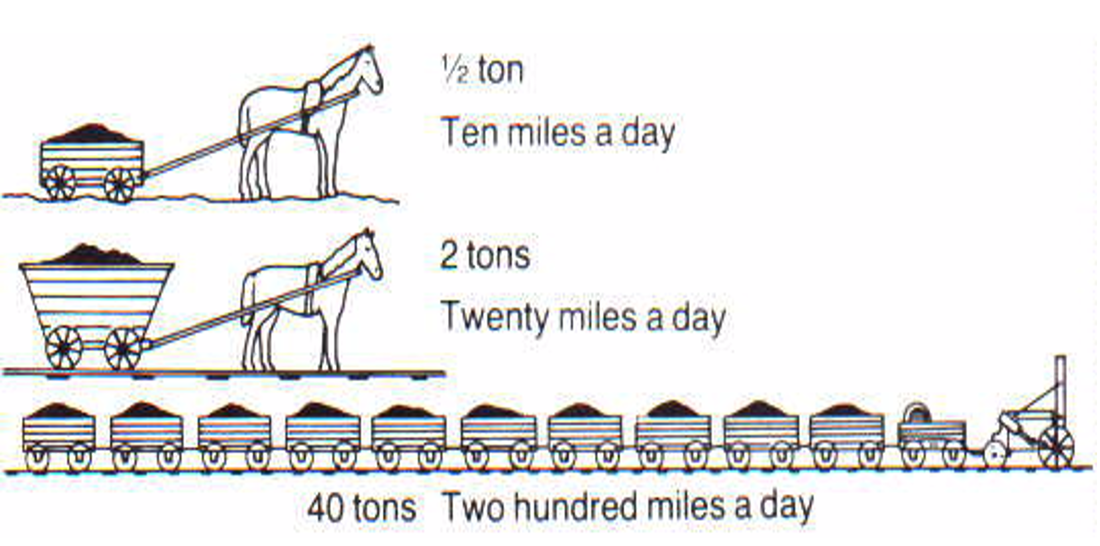

Even more important to the initial industrial growth of Britain was the building of canals. As we have seen, climate (rain) and physical geography (rivers, proximity to the sea and flat terrain) gave Britain advantages when it came to canals. And canals were essential as a means of transporting the very heavy raw materials - coal, iron ore and limestone - and the heavy finished goods from the mines, to the foundries and down to the ports. Again Britain produced engineers like Brindley and Telford (again) who overcame natural obstacles with brilliant innovations like locks and viaducts. The last decade of the 18th century has been described as the period of canal 'mania', where vast profits could be made through investing in canal building or the companies that directly benefitted. My favourite example is the Oxford canal which provided an annual 30% interest on an initial investment over 30 years. Go and put your money in a bank today and see how much you get!

|

|

|

Probably the innovation most associated with the Industrial Revolution was the steam locomotive. Boulton and Watt's low pressure steam engines did not have the power to move themselves, because in order to generate the power they had to become too big to move. Understand? In addition, as mentioned in an earlier lesson, Boulton and Watt used patents to stop business competitors from working with their inventions and potentially innovating. These patents ran out in 1800. Soon after the first successful steam locomotive to run on iron tracks was developed in South Wales (of course) and came about as a result of a bet between two rival iron masters in the town of Merthyr Tydfil.

Something extraordinary was happening in Wales 200 years ago when it basically became the world's first region to industrialise - and it would change the world... Dan Snow (BBC 2024).

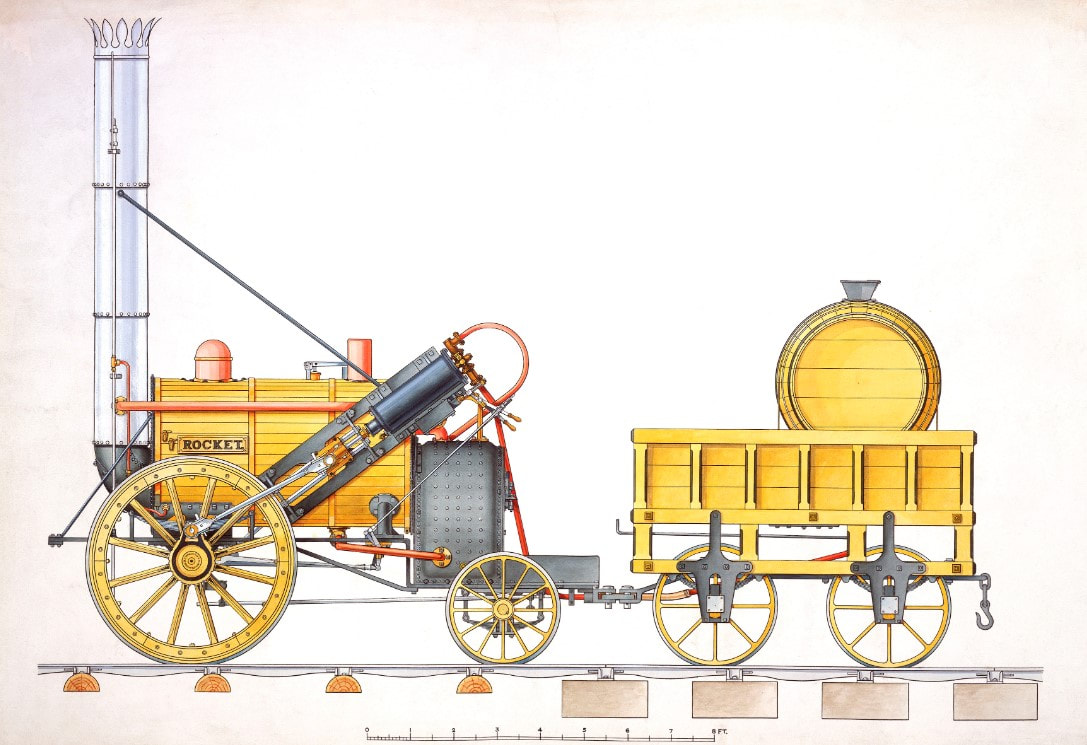

Despite impressive top speeds of up to 20kmh the novelty was not commercially viable (did not make money) and Trevithick went bankrupt in 1809. As a result, the father of the modern railway is considered to be George Stephenson. He was the engineer on the Stockton-Darlington railway which opened in 1825 and the more important Manchester-Liverpool which opened in 1830. His locomotive the Rocket, co-designed with his son Robert, incorporated many engineering innovations that enabled a top speed of nearly 50kmh, these were incorporated into future designs for generations to come. Importantly, this was commercially viable. The railway age had begun.

15th September 2022, marks the 192nd anniversary of the first fatality caused by a passenger railway, the death of government minister William Huskisson who was killed at the opening of the Manchester-Liverpool railway. Scott Allsop's HistoryPod (below) takes up the story

|

|

|

The consequences of the railway

We will consider the broader social and cultural impact of the railways in future lessons. Here we will look at some of the most direct, largely economic consequences.

We will consider the broader social and cultural impact of the railways in future lessons. Here we will look at some of the most direct, largely economic consequences.

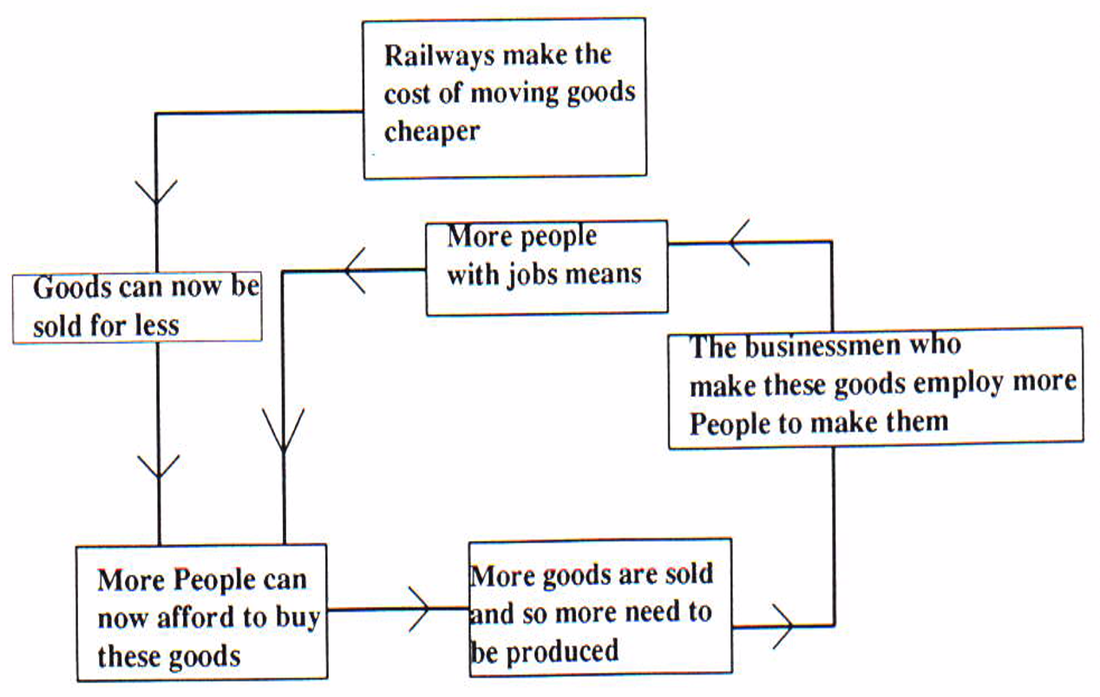

What impact did this have on the economy? The most important consequence is what economist call the 'multiplier effect'. The savings made in transport costs allowed industrialists to reduce the price of their goods. Because more people could afford to buy these goods this led to increased demand which encouraged higher levels of production. As industrialists made more profits they paid more dividends to share holders and invested more capital in new technology and buildings. More production required more raw materials, new factories and more workers. More workers meant more consumers and bigger towns. This increased the demand still further... and on and on and on.

|

The railways were also a communications revolution. It wasn't only people and raw materials and manufactured goods that began to speed their way across the country. Daily newspapers printed in London could now be delivered across the country the same day, keeping people informed of the latest political stories. People's outlook became less parochial and they were increasingly interested in national news.

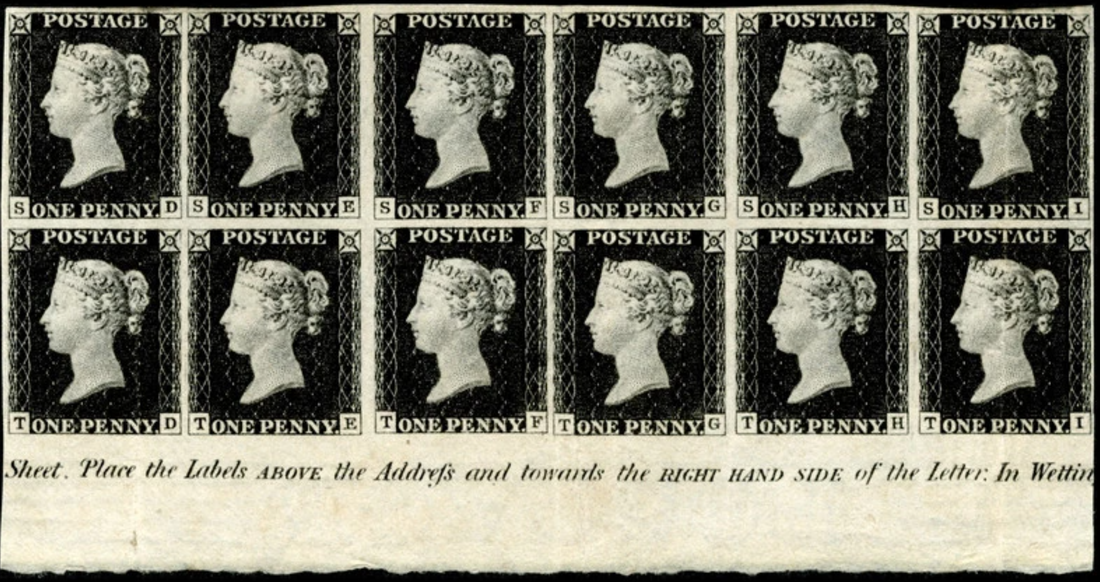

In 1840 Britain became the first country to introduce uniform, cheap, prepaid stamps (Switzerland was the second country) which revolutionised the postal service. (See the very first 'Penny Black' stamps below) Very soon after, special trains were created that allowed the mail to be sorted on the move, thus significantly speeding up delivery times. |

Railways even changed the time that people lived by. Before the railways, each part of the country had its own time, which was set when the sun reached midday in their area. The further west you travelled, you had to add 1 minute for every 16 km. When the railways were built this had to change as a number of train crashes were caused by trains running to different times. Station clocks, like the one below, began using London time. In 1880, Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) became everyone’s time in Britain and then the rest of the world.

|

These 'Penny Black' stamps are available to buy on line if you're interested.

|

|

|

Railways also provided a boost to the ongoing revolution in agriculture that we looked at in a previous lesson. Railways both reduced farmers transport costs which allowed the production of cheaper food and also increased transport speed which enabled farmers to provide fresher meat, fish, fruit and vegetables to the urban centres. Fish and chips became a British national dish made possible by the transportation of cheap, fresh fish to the cities.

|

|

|

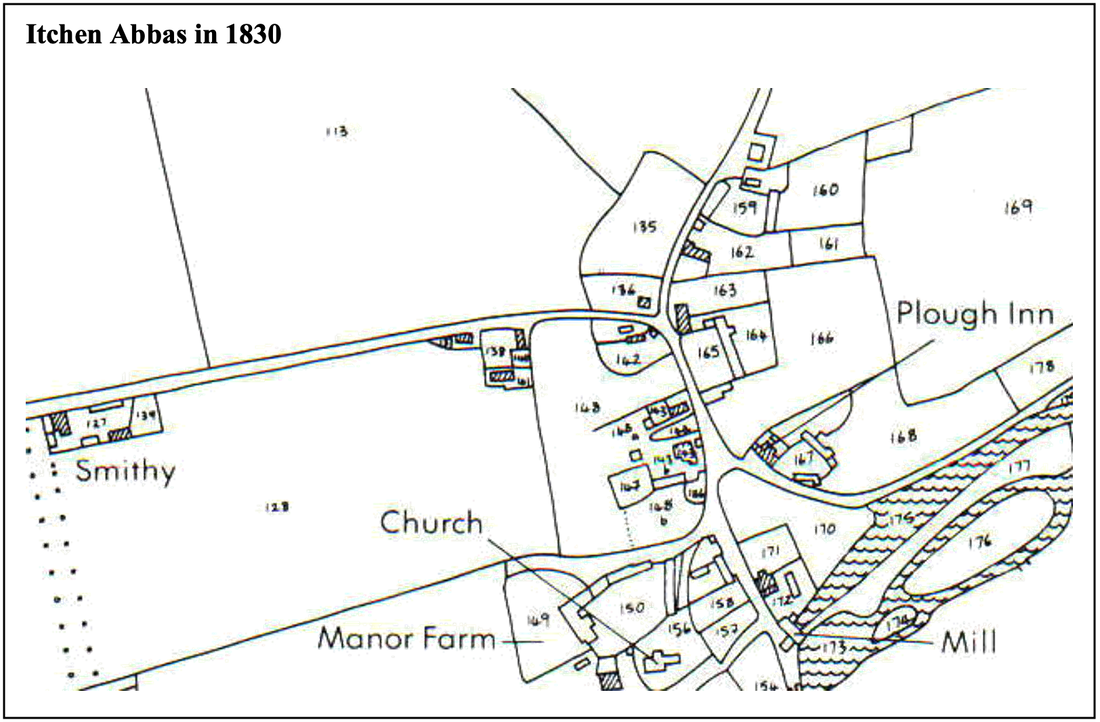

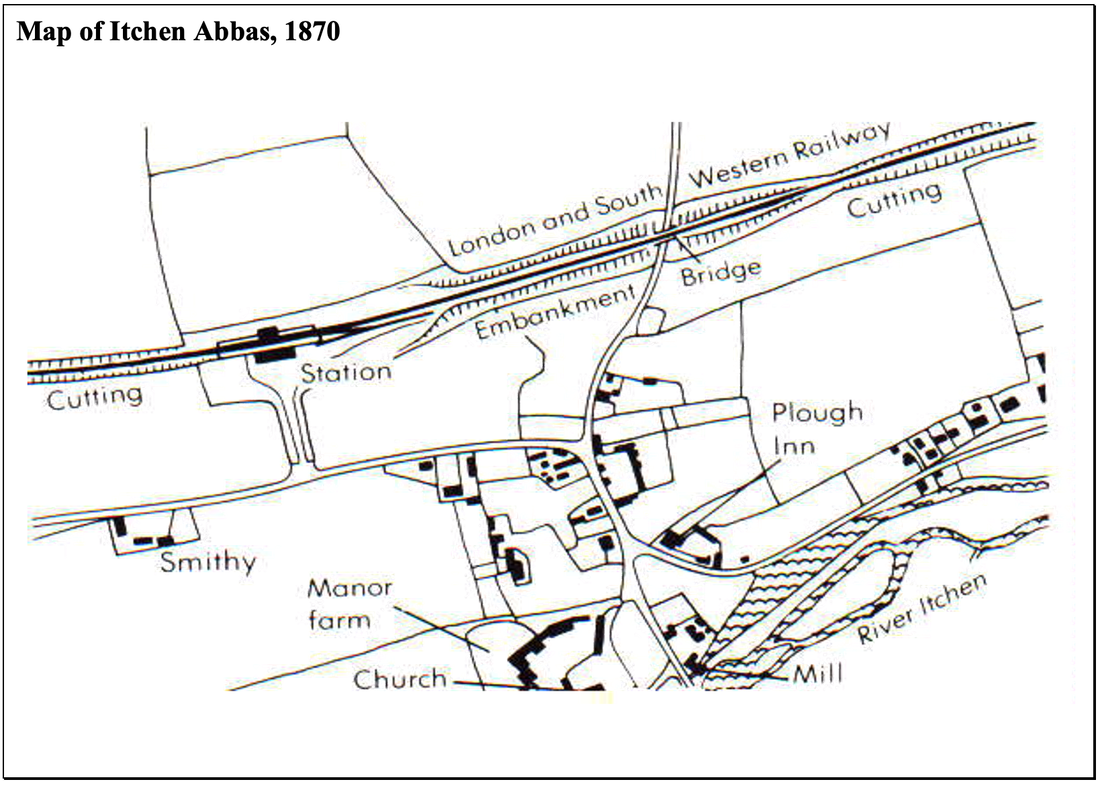

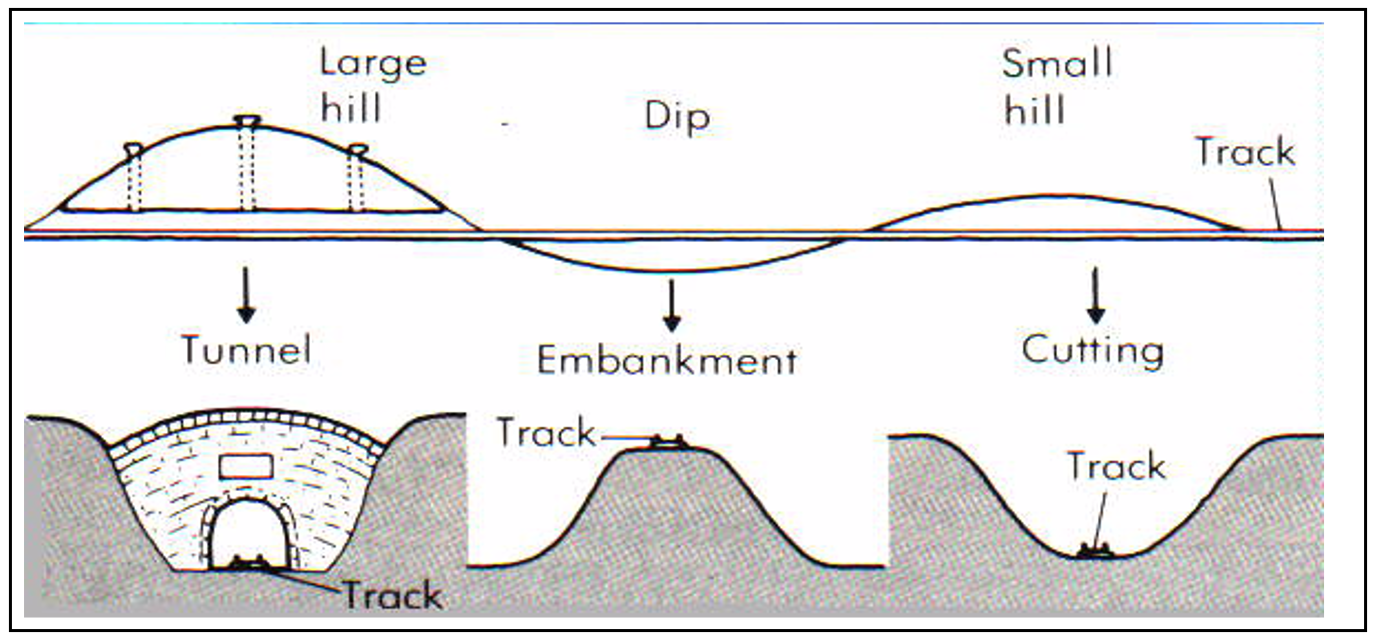

Finally, Railways had a significant impact on the physical environment. Railways work best going in a flat, straight line. This meant that engineers had to cut away slopes and build up embankments to ease the locomotive's passage. Where this was impossible, tunnels were built. Where tracks were laid, farmland had to be bought. And in villages where stations were built, the possibility of commuting created demand for new housing and pressure on local amenities. The village of Itchen Abbass in Hampshire provides us with a good case study of what happened.

|

Itchen Abbas case study

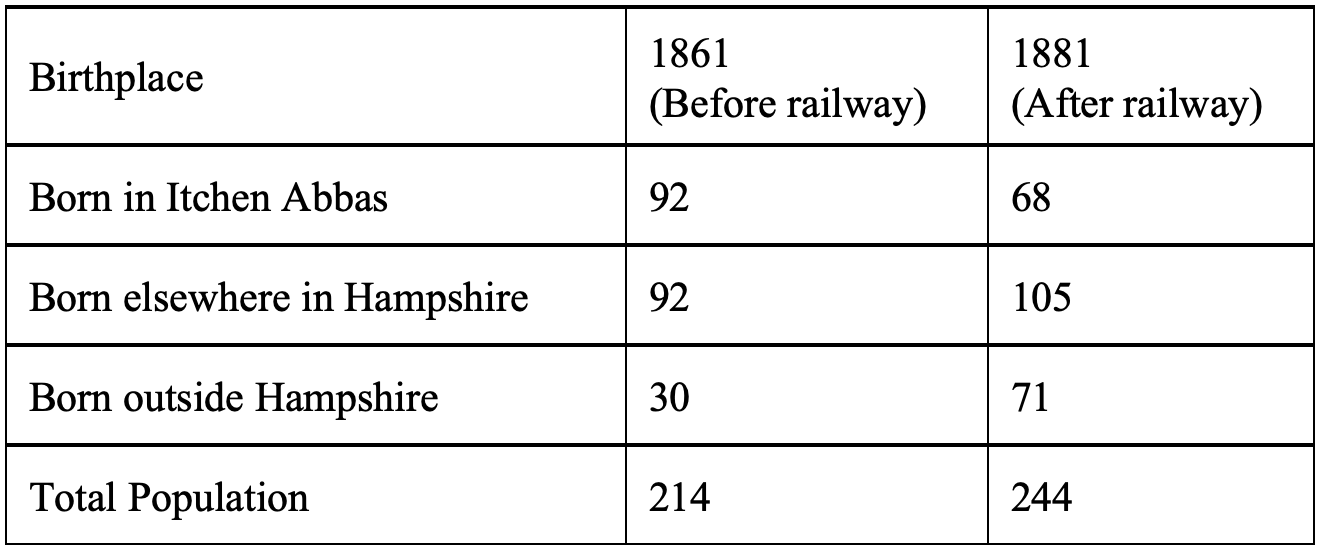

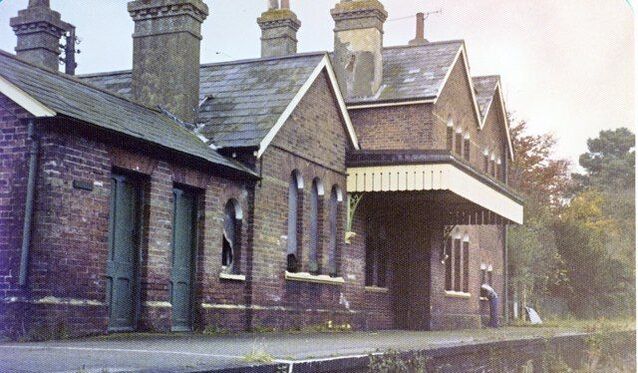

The Itchen Abbas railway station was in the county of Hampshire in England and opened on 2 October 1865 by the Alton, Alresford and Winchester Railway. Consider the following sources which illustrate its transformation by the railways.

|

Itchen Abbas was typical of many rural communities that were transformed by the railways. An isolated, rural community was opened up through a railway station that brought the outside world in. Farmland was built on, tracks were laid on land that was flattened or built up and the population grew.

|

Itchen Abbas railway station in 1979.

|

Activities

1. Explain why the development of roads and canals were essential to the early stages of the industrial revolution in Britain.

2. Who was Richard Trevithick? What was his contribution to the industrial revolution? Why is George Stephenson rather than Trevithick considered to be the father of the railways?

3. What were some of the main direct consequences of the development of the railway? (You must include the multiplier effect!)

4. Using the sources in the Itchen Abbas case study to support your answer, explain how small villages might be transformed by the coming of the railways. Also look at the current Google Map of the village. Is there any evidence that the railway ever existed?

1. Explain why the development of roads and canals were essential to the early stages of the industrial revolution in Britain.

2. Who was Richard Trevithick? What was his contribution to the industrial revolution? Why is George Stephenson rather than Trevithick considered to be the father of the railways?

3. What were some of the main direct consequences of the development of the railway? (You must include the multiplier effect!)

4. Using the sources in the Itchen Abbas case study to support your answer, explain how small villages might be transformed by the coming of the railways. Also look at the current Google Map of the village. Is there any evidence that the railway ever existed?

|

Extension

John Green takes an interestingly philosophical look at the impact of the railways which draws parallels with the technological changes of our own time. He also interestingly leads on to some of the social and cultural changes we'll be examining in future lessons. Dan Snow - who has become Mr TV History in the last few years - produced a good series on the history of the locomotive in 2013. I'm not a train-spotting type by any means, but I enjoyed the whole series. So here's a series for the long train/plane/automobile journey you have coming up. And remember, these are so much more useful than social media and cat videos. |

|

Locomotion: Dan Snow's History of Railways (BBC 2013)

Episode 1 looks at how, from their beginnings as track-ways for coal carts in the early 18th century, railways developed into the pivotal technology for modern Britain. Episode 2 traces the development of Britain's railways, from the beginnings of a true national network in the late 1830s through to the end of the 'railway mania' in 1847. Episode 3 traces the development of Britain's railways from the late 19th century to the outbreak of World War II. During this time the railways changed the economy profoundly.

Episode 1 looks at how, from their beginnings as track-ways for coal carts in the early 18th century, railways developed into the pivotal technology for modern Britain. Episode 2 traces the development of Britain's railways, from the beginnings of a true national network in the late 1830s through to the end of the 'railway mania' in 1847. Episode 3 traces the development of Britain's railways from the late 19th century to the outbreak of World War II. During this time the railways changed the economy profoundly.

|

|

|

|

Railways - The making of a nation (BBC4, 2016)

Another BBC series, more recent and more visual but covering similar themes and looking at the economic, social, cultural and political impact of the railways. Historian Liz McIvor examines how Britain's rapidly expanding railway network was the spark for a social revolution that began in the 1800s and whose impact is still being felt today.

Another BBC series, more recent and more visual but covering similar themes and looking at the economic, social, cultural and political impact of the railways. Historian Liz McIvor examines how Britain's rapidly expanding railway network was the spark for a social revolution that began in the 1800s and whose impact is still being felt today.

|

Capitalism and Commerce

The railways stimulated great changes to the nation's economy. They also changed the way we do business, encouraging a new generation of mechanical engineers, skilled workers, managers and accountants. Originally, local railway entrepreneurs viewed trains as vehicles for shifting raw materials, stock and goods. But soon they discovered there was money to be made in transporting people. But the railway boom of the 1840s also came with a 'bust'. A new age of middle-class shareholders who invested in the railways soon discovered what goes up can also go down. |

|

|

Time

This episode looks at how you organise a rail network in a country made up of separate local time zones and no recognised timetables. Before the railways, our country was divided and local time was proudly treasured. Clocks in the west of the country were several minutes behind those set in the east. The railways wanted the country to step to a new beat in a world of precise schedules and timetables that recognised Greenwich Mean Time. Not everyone was keen to step in line. |

|

|

The New Commuters

This episode looks at the railways enabled us to live further and further from the places where we worked. Before the age of steam you would need a horse to travel long distances on land. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries our railways encouraged the development of suburbia inhabited by a new type of resident and worker - the commuter. In some cases, new places emerged on the map simply because of the railways - places like Surbiton. The Victorian rail network was never part of a single grand plan, but emerged and evolved, line by line, over decades. |

|

|

The Age of Leisure

The very idea of an excursion to distant places became popular from the 1840s onwards. People were taking day trips and seeing parts of the country they had never seen before. However, it wasn't all seaside and sand. Some excursion trains were set up to satisfy the public's demand to witness public executions. Other lines transported people to enjoy horse racing and sporting events. Thousands visited resorts, spa towns and the coast. A new wave of Victorian tourists spent their cash on holidays and visited hotels at stations and beyond. |

|

|

Food and Shopping

The railways changed what we eat and the culinary tastes of the population. Moving produce around at speed was suddenly possible - fresh meat, wet fish, dairy, fruit and veg were now widely available. With a new system of rapid transport it was now possible for the capital to enjoy food supplies from all corners of the nation. Diets improved in terms of the variety and quality of food available. Victorian men and women developed a taste for one particular dish that would be popular with the masses for generations to come - fish and chips. |

|

|

A Touch of Class

Trains reflected class divisions with separate carriages for first, second and third class passengers. Yet, seen at the time, they were also bringing people physically closer together. In the early 1800s, Britain was clearly divided between upper, middle and working classes. But the trains gradually acted as a great catalyst, mixing the country up as people were travelling to regions and places for the first time. Locations, accents, culture and fashions were all new. Over time, we developed a stronger sense of shared identity and culture. |

|