Lesson 1 - What is modern authoritarianism?

|

|

|

Dictatorship is not democracy

Dictatorships or authoritarian regimes are a type of political regime in the same way that democracy is a type of political regime. This is an obvious but important point to make, because many history textbooks about authoritarianism often assume a false, absolute dichotomy that fails to appreciate that democracy and authoritarianism actually have a lot in common. The history student can be easily misled into thinking that only authoritarian regimes restrict the liberty of their citizens or use propaganda to attempt to shape public opinion. What history students can usefully learn from sociologists and political scientists is that governance and the exercise of power involve methods that are common to all regimes. It can also alert us to the fact that the dividing line between authoritarianism and democracy is not always a self-evident break, but rather an over-lapping continuum that is often in a state of flux.

Dictatorships or authoritarian regimes are a type of political regime in the same way that democracy is a type of political regime. This is an obvious but important point to make, because many history textbooks about authoritarianism often assume a false, absolute dichotomy that fails to appreciate that democracy and authoritarianism actually have a lot in common. The history student can be easily misled into thinking that only authoritarian regimes restrict the liberty of their citizens or use propaganda to attempt to shape public opinion. What history students can usefully learn from sociologists and political scientists is that governance and the exercise of power involve methods that are common to all regimes. It can also alert us to the fact that the dividing line between authoritarianism and democracy is not always a self-evident break, but rather an over-lapping continuum that is often in a state of flux.

|

Authoritarian regimes are most commonly defined in terms of what they are not. They are not democratic. The problem with this definition is that it assumes we know what democracy is. The term democracy originates from the Greek, ‘demos’ meaning ‘people’ and ‘kratos’ meaning ‘rule’. The ancient Athenian understanding of democracy involved the direct participation of all citizens in the political system. The modern version is representative democracy, in which citizens choose professional politicians to do the governing for them. The right of all citizens to elect their government is therefore what most people understand by democracy. But if we are to understand authoritarianism fully, we need to understand that democracy means more than voting once every five years.

|

|

A democracy has four key characteristics

The first characteristic of democracy is the importance of free and fair elections. By this we mean that elections involve the participation all citizens in a way that allows the individual to express their choice of representative without fear of recrimination. The right to vote should also happen with predictable regularity and at different administrative levels, from village elections to national elections or even trans-national elections. Elections often occur in authoritarian states, but they take place on an ‘uneven electoral playing field’. (Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way Competitive Authoritarianism p.6) Dictatorship may prevent elections from being fair by intimidating the opposition, denying their right to campaign or by vote-rigging the outcome.

The first characteristic of democracy is the importance of free and fair elections. By this we mean that elections involve the participation all citizens in a way that allows the individual to express their choice of representative without fear of recrimination. The right to vote should also happen with predictable regularity and at different administrative levels, from village elections to national elections or even trans-national elections. Elections often occur in authoritarian states, but they take place on an ‘uneven electoral playing field’. (Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way Competitive Authoritarianism p.6) Dictatorship may prevent elections from being fair by intimidating the opposition, denying their right to campaign or by vote-rigging the outcome.

|

The next important point is that elected officials must be accountable and removable. This requires the political system to have an inbuilt, official opposition whose job it is to hold government to account and to replace the government when it loses the support of the people. Holding a government to account means that an official opposition in the legislature (parliament) publicly examines in detail the policies and actions of the government. This is designed to encourage efficient governance, but also to prevent the corruption that is typical of authoritarian regimes.

|

Corruption Corruption occurs in all political systems. It is the abuse of office for private gain, for example, when state officials allocate a benefit in exchange for a bribe, rather than on the basis of entitlement. The bribe may persuade officials to do what they should have done anyway, or to do it more quickly. |

The third important characteristic of democracy is that all citizens, including ethnic and social minorities, have certain fundamental rights, guaranteed by law and usually written down in a state’s constitution. For example, the right to worship the religion of your choice or the right to privacy in the home are basic rights in a democracy. Freedom of speech, or the freedom of the media to criticise those in positions of authority, are amongst the first freedoms to be denied in any authoritarian state.

The last important characteristic of democracy is equality. The state must respect each individual equally, irrespective of their social position, political affiliation or economic status.

The last important characteristic of democracy is equality. The state must respect each individual equally, irrespective of their social position, political affiliation or economic status.

|

Everyone must be treated equally before the law. To help enforce this, the judiciary - the system of courts that interprets and applies the law – must be independent from the executive (government). In addition, the institutions that enforce the law – the police and the army – must be accountable to the civilian authority of elected representatives. In many authoritarian states, the judiciary if is too weak and the army too politicized to guarantee equality of all citizens before the law. A society in which there is significant social and economic inequality cannot be democratic, because the existence of social/economic elites will inevitably undermine the principal that all in in society must be treated the same. The video (right) illustrates why democracy in the USA is under threat. The situation is much worse now than it was when the film was made in 2012.

|

|

|

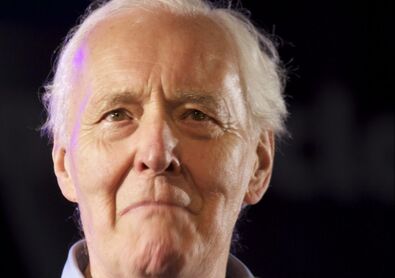

Tony Benn – Five little democratic questions

‘If one meets a powerful person--Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin or Bill Gates--ask them five questions: “What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? And how can we get rid of you?” If you cannot get rid of the people who govern you, you do not live in a democratic system.’ Tony Benn (1925-2014), MP for Chesterfield, England. 22 March 2001. |

|

What is modern authoritarianism?

Nondemocratic states may have been the norm for most of human history, but in the first half of the 20th century a new form of ‘modern’ authoritarian state emerged in Lenin’s Russia, Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. The ‘modernity’ of these regimes can be seen in three defining characteristics of modern authoritarianism. Firstly, modern authoritarian states were/are consciously modern and did not and could not rely upon traditional forms of authority – ‘it is like this because it has always been like this’ – to justify their rule. Unlike a hereditary absolute monarch, such as the Tsar in Russia, the legitimacy of Bolshevik Russia, initially at least, did not derive from rightful family or dynastic succession from father to son. |

|

|

As Juan Linz, the world authority on authoritarian states, explained, ‘there are those who call Latin American authoritarian... regimes "traditional"; some even do so in the cases of Franco's Spain and Salazar's Portugal. This interpretation is fundamentally flawed, however, since the basis of legitimacy in the regimes is not traditional dynastic legitimacy.’ (Juan J. Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, Riener 2000, p.11)

|

Legitimacy Legitimacy is the popular acceptance of an authority, usually a governing law or a régime, because the authority is considered to have the right to govern. In a democracy, a government is legitimate if it has been elected to power. |

The second characteristic difference of modern authoritarianism is the importance of ideology. In the absence of either inherited or electoral legitimacy, rule had to be justified ideologically. The authoritarian states that emerged after the First World War were defined by their ideological rejection of the progressive liberalism of the 19th century. This was not the same as the ancient monarchies blindly resisting liberalism and democratization in the late 19th century. The new authoritarianism proposed an alternative ideological basis to liberalism, whether in fascist or communist form.

The third distinctly modern feature of 20th century authoritarianism, involved the centralization and industrialization of the mechanisms of state control. The old authoritarian regimes ruled over a largely illiterate and isolated, rural peasantry. Control was exercised by local authority, reinforced through religious conventions and guaranteed by national force. Modern authoritarianism’s ambition to rule over an industrial, urban and connected citizenship, required an increasingly sophisticated, integrated form of layered formal and informal social control, using, for example, all the most sophisticated of modern communication technology, to spread the ideological message of the regime. If the traditional authoritarian regimes had been bolstered by the church, modern authoritarianism required a secular equivalent in the state-controlled newspapers, radio and cinema.

Social Control

Social control refers to the processes that regulate individual and group behavior in an attempt to gain conformity to the rules of a given society, state, or social group. Sociologists identify two basic forms of social control:

Informal social control means the individual internalization of norms and values by a process known as socialization. The state – or other powerful organizations - can attempt to influence informal social control through its control of education and the media.

Formal social control means external sanctions enforced by government though laws and the punishment of legally defined criminal deviants’. Émile Durkheim, one for the founding fathers of sociology refers to this form of control as regulation.

Social control refers to the processes that regulate individual and group behavior in an attempt to gain conformity to the rules of a given society, state, or social group. Sociologists identify two basic forms of social control:

Informal social control means the individual internalization of norms and values by a process known as socialization. The state – or other powerful organizations - can attempt to influence informal social control through its control of education and the media.

Formal social control means external sanctions enforced by government though laws and the punishment of legally defined criminal deviants’. Émile Durkheim, one for the founding fathers of sociology refers to this form of control as regulation.

Why is it important to study authoritarian states?

|

Authoritarian regimes have always been important. As Paul Brooker puts it, 'non-democratic government, whether by elders, chiefs, monarchs, aristocrats, empires, military regimes or one-party states, has been the norm for most of human history' (P. Brooker, Non-Democratic Regimes: Theory, Government and Politics, 2nd edn (2009).p.1) But perhaps more importantly, studying authoritarian states is not merely a historical exercise. The latest (2021) report of the human rights watchdog organisation Freedom House concludes that only 88 (45%) of countries in the world today are ‘free’ and that over the last decade, democracy has globally been in decline. Therefore, despite the apparent grounds for democratic optimism engendered by post-World War II decolonisation, the collapse of the USSR or the Arab Spring of 2011, the world is not necessarily becoming any more democratic.

|

|

On the one side we have what Paul Brooker describes as ‘camouflaged or disguised dictatorships which claim to be democratic’. (Brooker, Non-Democratic Regimes: p.1) Current (2014) In this respect, regimes in Nigeria, Indonesia, Venezuela and Russia might be controversially identified as ‘grey zone’ regimes. (‘Thinking About Hybrid Regimes’ - Larry Jay Diamond, Journal of Democracy Volume 13, Number 2, April 2002 pp. 21-35) These regimes have democratic institutions and elections, but opposition victories in elections are very unlikely and human rights abuses are all too common.

On the other side of the divide, we also have to recognise that many long-established democratic regimes have, over the last few decades, dramatically enhanced their capacity to monitor and control the words and actions of individual citizens, as evidenced by the campaigns of WikiLeaks or NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden. With CCTV, Electronic Payment Systems, personal GPS enabled devices, biometric identity cards and genetic fingerprinting, the 21st century state has the means of tracking citizens that goes well beyond even the nightmarish imagining of George Orwell’s 1984. As Snowden himself argued in his 2014 testimony to the Council of Europe, ‘Technology represents the most significant new threat to civil liberties in modern times’ (8 April 2014). In conclusion therefore, being able to identify the key features of authoritarian regimes that claim to be democratic is one of key skills of modern citizenship.

On the other side of the divide, we also have to recognise that many long-established democratic regimes have, over the last few decades, dramatically enhanced their capacity to monitor and control the words and actions of individual citizens, as evidenced by the campaigns of WikiLeaks or NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden. With CCTV, Electronic Payment Systems, personal GPS enabled devices, biometric identity cards and genetic fingerprinting, the 21st century state has the means of tracking citizens that goes well beyond even the nightmarish imagining of George Orwell’s 1984. As Snowden himself argued in his 2014 testimony to the Council of Europe, ‘Technology represents the most significant new threat to civil liberties in modern times’ (8 April 2014). In conclusion therefore, being able to identify the key features of authoritarian regimes that claim to be democratic is one of key skills of modern citizenship.

Activities

Read the text and watch the short films and then provide full explanations for the following questions:

Read the text and watch the short films and then provide full explanations for the following questions:

- What is a democracy?

- What three arguments have been used by those who oppose democracy?

- What is modern authoritarianism?

- Why is the study of authoritarianism important?

|

Extra and extension

This short Vox film from 2016 examines the rise of 21st century modern authoritarianism. It explains how Trump was able to appeal to certain types of American voters and how that he might even be elected president. But not even this film was able to predict his attempted Washington coup d'etat. This August 2022 article by George Monbiot illustrates how democracy continues to be a problem for the ruling economic elite in Britain. |

|

|

|

Dictators and Despots - BBC 2017

In recent years the world has become an unsettling place, from the mass movements of refugees to political upheaval, both in this country and abroad. Disturbingly, history shows that it's at unsettled times like these that dictators can rise - leaders who promise they can solve every problem, if only they're granted supreme power. David Olusoga examines fifty years of BBC documentary archives to try and discover why dictators can have such a powerful appeal. He questions why such men continue to fascinate us regardless of their actions, and asks whether, especially in an age of mass media, our fascination has fed their power. |