Lesson 2 - What was the impact of Napoleon and the Vienna settlement?

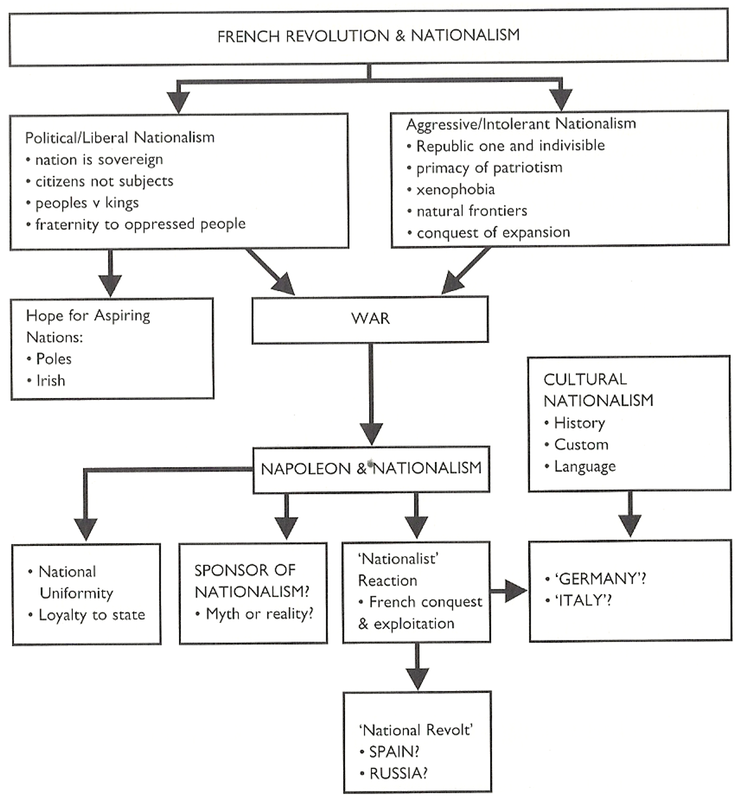

It can be argued that Napoleon's empire encouraged nationalism in two ways: positively and negatively. As a result of the reorganisation of Europe under Napoleon's rule (Matu 3 - lesson 7) a new positive sense of national identity was made possible by Napoleon's breaking down of the old feudal order and replacing it with more efficient centralised (national) systems of government. But also, the negative experience of Napoleon's rule also encouraged organised opposition who collectively defined themselves (nationally) against French rule.

|

|

How did Napoleon postively encourage Italian and German nationalism?

Napoleon reorganised the Italian state system and as a consequence Italy was more united - Savoy and Nice were annexed, the Cisalpine and Ligurian republics were created; later the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Naples were set up. Administrative systems copied more or less the French approach, the French civil law code, the Code Napoleon, was exported and customs regulations were simplified. However, it is also clear that the reorganisations of states and the re-drawing of boundaries were carried out to serve the interests of France and Napoleon: the Italian provinces, just as we saw in Switzerland were exploited to help supply and finance the French war machine. |

Napoleon made similar ‘I encouraged nationalism’ claims about Germany and a similar story emerges here - the Holy Roman Empire disappeared in 1806 and the chaotic system of over 300 states, princedoms, ecclesiastical principalities and free cities was rationalised. As in Italy new kingdoms were created (such as Westphalia) and some parts were absorbed directly into the Empire (such as the Rhineland). Older states were rewarded for their loyalty by expansion (as in Bavaria) and a new federation established (the Confederation of the Rhine). As in Italy the Code Napoleon was exported, administrative systems were reorganised as in France, and customs regulations were simplified. But, also as in Italy, it is hard to see in this some entire plan to create a German nation state; the aim, as we saw in Switzerland, was rather to provide reliable allies on the borders of France and territories to be exploited for the benefit of France and her armies.

|

How did nationalism arise as a negative resistance to Napoleon?

Many historians have pointed out that what nationalism existed in the Napoleonic period was developing in opposition and resistance to the French; it was not the product of Napoleon's positive encouragement. In Spain, for instance, the long, sporadic war against France combined traditional loyalties to Church and King with resistance to paying French taxed. Priests since the 1790s had preached that the French revolutionaries were atheists and therefore to be detested and a foreign-imposed monarch and an army of occupation was less acceptable than Spain's hereditary monarchy, however flawed. |

|

More significant were the stirrings of nationalism in Germany and Italy. Before Napoleon's invasion in 1796 there is little evidence of any desire for a united Italian state. It was Italian sympathisers with the French Revolution who first defined the idea of a united Italy as an aim. The influence of the French revolution meant that at this stage Italian nationalism found expression in the idea of an association of free citizens who were free from oppression. Italian intellectuals wrote essays on the form the new Italy should take, suggesting, for instance, either a federation recognising regional differences or a single unitary Republic.

In Germany, that assortment of states that occupied central Europe north of the Alps, there were signs of a developing national consciousness, at least among the educated elites, in the late eighteenth century. This had begun independently of the French Revolution but was given new momentum in reaction to it and the exploitation of Napoleon. The cultural nationalism that had begun to develop in Germany with its interest in the history and folk memory of the Volk (loosely translated as the 'people'), however, did not imply the development of a nation state.

But the appeal to 'Germans' (a people united by culture and history) could be invoked against the French. The defeat of Prussia at Jena-Auerstadt in 1806, in particular, was, as Hagen Schulze has put it, 'the first spark which set German nationalism alight'. There were intellectuals like Fichte who’s 'Lectures to the German Nation' in 1807-8 in Berlin met with an enthusiastic response. Frederick William III of Prussia was finally persuaded to take up arms against Napoleon in 1813 and issued an appeal calling on 'Prussians and Germans' to fight.

Units were formed from students and artisans (not peasants). Their songs spoke of the 'fatherland' and freedom'. There was no aspiration to a German state in this, more a hatred of the French and an association with a 'German nation' determined by a common language and culture. This linguistic and/or cultural criterion was, however, to play a significant role in the development of nationalism in the nineteenth century, especially in those areas subject to 'foreign' rule, like Italy, or in those areas with several different states like 'Germany'. The emphasis on a common language, history or culture helped to emphasise what united people in these areas when so much else divided them - rulers, social status, rights and privileges.

In Germany, that assortment of states that occupied central Europe north of the Alps, there were signs of a developing national consciousness, at least among the educated elites, in the late eighteenth century. This had begun independently of the French Revolution but was given new momentum in reaction to it and the exploitation of Napoleon. The cultural nationalism that had begun to develop in Germany with its interest in the history and folk memory of the Volk (loosely translated as the 'people'), however, did not imply the development of a nation state.

But the appeal to 'Germans' (a people united by culture and history) could be invoked against the French. The defeat of Prussia at Jena-Auerstadt in 1806, in particular, was, as Hagen Schulze has put it, 'the first spark which set German nationalism alight'. There were intellectuals like Fichte who’s 'Lectures to the German Nation' in 1807-8 in Berlin met with an enthusiastic response. Frederick William III of Prussia was finally persuaded to take up arms against Napoleon in 1813 and issued an appeal calling on 'Prussians and Germans' to fight.

Units were formed from students and artisans (not peasants). Their songs spoke of the 'fatherland' and freedom'. There was no aspiration to a German state in this, more a hatred of the French and an association with a 'German nation' determined by a common language and culture. This linguistic and/or cultural criterion was, however, to play a significant role in the development of nationalism in the nineteenth century, especially in those areas subject to 'foreign' rule, like Italy, or in those areas with several different states like 'Germany'. The emphasis on a common language, history or culture helped to emphasise what united people in these areas when so much else divided them - rulers, social status, rights and privileges.

|

How far had nationalism developed in Europe by 1815? In brief, not very far outside of France and England. The concept of a state comprising a nation of equal citizens had been born. Within France, arguably, a sense of national consciousness had penetrated the masses, especially in the towns and cities. Its features included a commitment to constitutional government that guaranteed equality before the law and other rights, and a strong sense of national pride. The uniform systems of government and the centralised state helped to bind Frenchmen together. On the continent outside France, however, nationalism was, like liberalism, largely confined to the professional and educated middle classes and a few 'enlightened' members of the aristocracy. In Germany, it amounted to little more than vague national goals and a sense of cultural community within academic circles in the universities. But, however limited, its presence amongst the middle classes meant it represented a potentially powerful threat to the traditional authorities. |

Congress of Vienna 1815

By this part of the lesson I predict that I will be too tired to keep talking, so I thought I'd let your old friend John Green take over. I have set you some questions to answer though, so you can't just start dropping off to sleep...

By this part of the lesson I predict that I will be too tired to keep talking, so I thought I'd let your old friend John Green take over. I have set you some questions to answer though, so you can't just start dropping off to sleep...

|

|

|

Switzerland (because John Green doesn't mention it...)

In December 1813 the Swiss Diet (assembly) declared the end of Mediation regime. In some conservative cantons the old powerful families attempted to once again take power, for example Berne, Lucerne and Valais. But in other parts of Switzerland peasants demonstrated to defend their newly acquired rights. Civil War seemed likely, but under pressure from the Great Powers, notably the Russians, (and thanks to the relationship with Tsar Alexander's old tutor Frédéric-César de La Harpe from Rolle) a new ‘Long Diet’ was established in order to make a new constitution. The Great Powers insisted that there would be no return to the past. The cantons created by Napoleon were to remain, Vaud for example retained its independence and three new cantons were added - Geneva, Neuchatel and Valais. In addition, the concept of a Swiss Confederation was formally used for the first time. The national Diet was to be responsible for trade, diplomacy and defence and a national Swiss army was created for the first time.

In December 1813 the Swiss Diet (assembly) declared the end of Mediation regime. In some conservative cantons the old powerful families attempted to once again take power, for example Berne, Lucerne and Valais. But in other parts of Switzerland peasants demonstrated to defend their newly acquired rights. Civil War seemed likely, but under pressure from the Great Powers, notably the Russians, (and thanks to the relationship with Tsar Alexander's old tutor Frédéric-César de La Harpe from Rolle) a new ‘Long Diet’ was established in order to make a new constitution. The Great Powers insisted that there would be no return to the past. The cantons created by Napoleon were to remain, Vaud for example retained its independence and three new cantons were added - Geneva, Neuchatel and Valais. In addition, the concept of a Swiss Confederation was formally used for the first time. The national Diet was to be responsible for trade, diplomacy and defence and a national Swiss army was created for the first time.

Activities

Read through the above text very carefully. On the Napoleon section answer the questions that were posed in the text. That is:

How did Napoleon encourage Italian and German nationalism?

How did nationalism also arise in resistance to Napoleon?

How far had nationalism developed in Europe by 1815?

Finally, make a few notes in answer to the question, how did the Treaty of Vienna impact Switzerland?

p.s. I will add your completed John Green Treaty of Vienna notes when you are finished.

Read through the above text very carefully. On the Napoleon section answer the questions that were posed in the text. That is:

How did Napoleon encourage Italian and German nationalism?

How did nationalism also arise in resistance to Napoleon?

How far had nationalism developed in Europe by 1815?

Finally, make a few notes in answer to the question, how did the Treaty of Vienna impact Switzerland?

p.s. I will add your completed John Green Treaty of Vienna notes when you are finished.

Extra

|

|