Lesson 6 - The 18th century and Napoleonic Wars

Big questions and some more answers

In the last lesson we once again addressed some of those big questions about warfare that we set out at the start of this unit. We saw how once again religion could be an important cause of war and also how wars fought for religious ends could be particularly brutal. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre and the Thirty Years War are both powerful illustrations of what humans are capable of doing when they believe that God is on their side. The Protestant Reformation and the religious wars that followed were also significant turning points in world history, the consequences of which still resonate today. Divisions between Catholics and Protestants continue to influence politics and society in Europe and even here in Switzerland.

Finally, we once again looked at heritage and memorial. The celebration of the life and death of Gaspard de Coligny in the painting of François Dubois in Lausanne or his statue on the Reformation Wall in Geneva, tell us as much about the artists and societies that created them as they do about de Coligny himself. In this lesson we are once again going to look at heroes and memorials. As we saw a few lessons ago it is longer is it acceptable to tell stories of the past that ignore the voices of those that were defeated or the victims. Where once we built statues to heroes, we now question what it means to be a hero. In this lesson we are going to look at one of the most famous of modern heroes Napoleon Bonaparte (Matu 3).

In the last lesson we once again addressed some of those big questions about warfare that we set out at the start of this unit. We saw how once again religion could be an important cause of war and also how wars fought for religious ends could be particularly brutal. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre and the Thirty Years War are both powerful illustrations of what humans are capable of doing when they believe that God is on their side. The Protestant Reformation and the religious wars that followed were also significant turning points in world history, the consequences of which still resonate today. Divisions between Catholics and Protestants continue to influence politics and society in Europe and even here in Switzerland.

Finally, we once again looked at heritage and memorial. The celebration of the life and death of Gaspard de Coligny in the painting of François Dubois in Lausanne or his statue on the Reformation Wall in Geneva, tell us as much about the artists and societies that created them as they do about de Coligny himself. In this lesson we are once again going to look at heroes and memorials. As we saw a few lessons ago it is longer is it acceptable to tell stories of the past that ignore the voices of those that were defeated or the victims. Where once we built statues to heroes, we now question what it means to be a hero. In this lesson we are going to look at one of the most famous of modern heroes Napoleon Bonaparte (Matu 3).

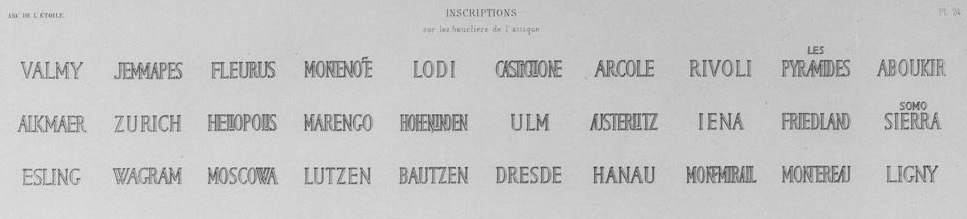

Heritage Object - Arc de Triomphe, Paris

|

|

The Arc de Triomphe in Paris is one of the most recognisable (and most visited) monuments in the world, although most people actually know little about its history and what is represents. It was commissioned in 1806 by Napoleon to commemorate his greatest victories (see above) and the names of over 500 of his generals. It wasn't completed until long after the defeat (1815) and death (1821) of Napoleon in 1836.

|

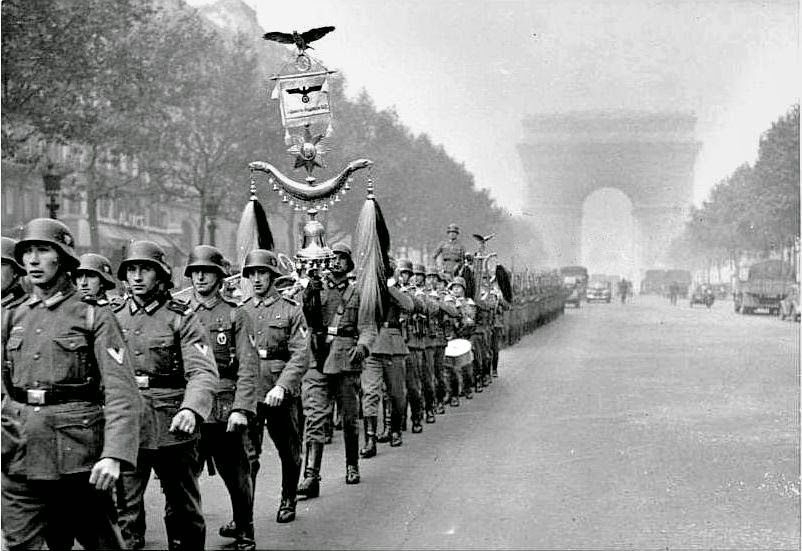

But as these images below show, the Arc de Triomphe means much more to the French today than a mere Napoleonic memorial. Click on the images below for a closer look.

A bit of background

In the second half of this first semester we are going to look at warfare through a series of events that will preview topics to be covered in detail later in the Matu syllabus. My aim is to give you a chronological overview of events that shows how these things are connected together. This is why your continued work on the timeline is an important ongoing project.

The changing nature of warfare.

In the second half of this first semester we are going to look at warfare through a series of events that will preview topics to be covered in detail later in the Matu syllabus. My aim is to give you a chronological overview of events that shows how these things are connected together. This is why your continued work on the timeline is an important ongoing project.

The changing nature of warfare.

|

As we saw last lesson after the middle ages, states became increasingly centralised (see Matu 1) and an ability to fund an army became more important. But rather than relying on mercenaries, increasingly powerful monarchs began to fund full-time professional armies of their own. Finding the money to pay for these armies led to greater centralisation of power and more efficient tax raising methods. One important way of raising money was to sell 'commissions'; that is, if you wanted to be an officer you had to buy your 'commission'. At this time more than nine out of ten officers were from the nobility. The most important officers were the most important nobility. The ordinary soldiers for these professional armies came from the lowest classes, often social drop-outs and criminals who were 'press-ganged' into joining. (see image right from 1780). To keep discipline, extreme corporal punishment was common.

|

These were not national armies. They fought 'dynastic wars' between royal families. The wars that were fought had limited ambitions set by the kings themselves. Kings often led their army on the battlefield and went to war again fellow kings in order to win more territory or better trading rights. A good example of a limited war was the War of Bavarian Succession from July 1778 to May 1779 where there was a Saxon-Prussian alliance in order to fight against the Austrian Habsburgs. The King of Prussia, Frederick II, was did not want to risk attacking as Prussia was deprived of resources and as a result there were no significant battles. As this example show, armies were so expensive to maintain that kings were very reluctant to use them. During the Seven Years War (1756-63 see Matu 1) the French lost as much as a fifth of their army each year due to disease, desertion and battle, requiring 50,000 replacements annually. This was very expensive to maintain, so battles were often settled when one king realised that his opponent was likely to win. There was an unspoken agreement between fellow aristocratic leaders on the rules that conducted warfare which also meant they often didn't fight at all.

A historian describes the 'limited war' of the 18th century

The term most commonly applied to warfare in the eighteenth century is ‘limited’. The period is usually portrayed as an age of restrained warfare between rival kings, fought for limited objectives rather than the complete destruction of their opponents. Warfare was also limited in its impact on the civilian population, with soldiers deliberately distanced from civilians during both war and peace. During peacetime the men at arms were quartered separately in barracks and were paid, supplied and fed by the king to prevent the violent exploitation of the host population, and to minimise the risk of desertion... In moral terms there was a general acceptance of the need for a civilised code of behaviour for the conduct of war. This arose from two sources: firstly, a revulsion against the horrors of unlimited warfare as demonstrated by the religious struggles of the Thirty Years War (1618-48), and secondly, the humanising influence of the ideas of the Enlightenment. Kings, such as Frederick II, now fought for limited, material goals such as a fortress, a slice of territory or a colony, not for ideological causes and the complete annihilation of their enemy. Europe had learnt the hard way that questions of religion would not be settled on the battlefield.

Neil Stewart - The changing nature of warfare 1700-1945

The image shows Frederick the Great advancing with a Flag at the Battle of Zorndorf, from the painting by Carl Röchling

Living in an army camp was more dangerous than fighting on the battlefield. Dysentery and syphilis were two of the most common diseases. Treatment of casualties was very limited. The French were the best and in the 1780s they only had 1200 doctors for 200,000 troops. Brandy was the most common ‘anaesthetic’ for operations. Between 1793 and 1815, Britain lost 240,000 soldiers of whom only 27,000 died in battle.

|

|

'...I must confess that I did not bear the amputation of my arm as well as I ought to have done, for I made noise enough when the knife cut through my skin and flesh. It is no joke I assure you, but still it was a shame to say a word, and is of no use...his instruments were blunted, so it was a long time before the thing was finished, at least twenty minutes, and the pain was great. I then thanked him for his kindness, having sworn at him like a trooper while he was at it...' General Napier, Peninsula War |

Finally also as we saw last lesson, new technology in warfare began to change the way wars were fought. Perhaps the single most important development in the early 18th century was the addition of a bayonet to the musket which ended the role of the pikemen. You can see muskets with bayonets attached in the painting of the battle of Jersey from the American Revolutionary wars below. At the same time the matchlock musket, ignited manually from a slow burning fuse (Lesson 4), was replaced by the more reliable, and faster, flintlock musket (see below), which produced its own spark. The flintlock muskets were lighter and therefore needed no prop or rest for the barrel. They could fire three rounds a minute, which was twice as quick as previously.

|

Activities

Part 1 - The changing nature of warfare in the 18th century This activity is divided in two. Before you go on to look at the case study, check your understanding of the section above by answering the following four questions:

Part 2 Case Study - 1796 The Battle of Lodi. |

|