Lesson 7 - The political consequences of the Industrial Revolution

The political consequences of the Industrial Revolution.

A preliminary note.

The syllabus for the Matu history programme is relatively typical on the industrial revolution, similar to every other programme I have taught. Apart from this section. On the politics we are required to ‘faire une étude comparative des théories communistes de Karl Marx et des mouvements présocialistes.’ We will be doing Marxism in some detail later this year, so in this section we’ll mainly be looking at pre-Marxist movements i.e., popular movements - socialist or otherwise - that were inspired by the French Revolution and that opposed the consequences of industrialisation.

What is meant by political consequences?

‘Political’ consequences are concerned with how traditional pre-industrial systems of power and governance were challenged by new types of people, with new ways of thinking about how the country should be run. These new types of people were the middle and working classes we studied in Lesson 5. In 1750 the political system in Britain, like every other European country, was still dominated by aristocratic landowners. There were however two important differences. Firstly, as a result of a political revolution and civil war in the mid 17th century, (Britain had beheaded its king in 1649), Britain had established a parliamentary system of government and a constitutional monarchy as early as 1688.

A preliminary note.

The syllabus for the Matu history programme is relatively typical on the industrial revolution, similar to every other programme I have taught. Apart from this section. On the politics we are required to ‘faire une étude comparative des théories communistes de Karl Marx et des mouvements présocialistes.’ We will be doing Marxism in some detail later this year, so in this section we’ll mainly be looking at pre-Marxist movements i.e., popular movements - socialist or otherwise - that were inspired by the French Revolution and that opposed the consequences of industrialisation.

What is meant by political consequences?

‘Political’ consequences are concerned with how traditional pre-industrial systems of power and governance were challenged by new types of people, with new ways of thinking about how the country should be run. These new types of people were the middle and working classes we studied in Lesson 5. In 1750 the political system in Britain, like every other European country, was still dominated by aristocratic landowners. There were however two important differences. Firstly, as a result of a political revolution and civil war in the mid 17th century, (Britain had beheaded its king in 1649), Britain had established a parliamentary system of government and a constitutional monarchy as early as 1688.

The English Civil War, the execution of King Charles I and the republic that followed is important, but these events are not on the Matu nor something the English are awfully proud of... so i'll just put a couple of useful videos here for those who want to find out more.

|

|

|

Anyway, moving on. This system of government had ended the absolutist control of the king and had established a more ‘liberal’ political culture than was the case in mainland Europe. As we have seen, (Lesson 1) this is perhaps one of the most important reasons why Britain was the first country to experience the Industrial Revolution.

The second reason for the political differences with continental Europe concerned what happened after 1805. Britain unlike most of continental Europe retained her independence from Napoleonic influence. In contrast to Europe - which had experienced military defeat and political revolution - British government did not need to be ‘restored’ in 1815. Therefore, because it had slowly evolved over time, (or at least since they cut off the head of a king that we don't talk about) the tradition of the British system of government was perhaps more stable and secure. If political systems have been in place for a long time, they are more likely to last for a long time.

The second reason for the political differences with continental Europe concerned what happened after 1805. Britain unlike most of continental Europe retained her independence from Napoleonic influence. In contrast to Europe - which had experienced military defeat and political revolution - British government did not need to be ‘restored’ in 1815. Therefore, because it had slowly evolved over time, (or at least since they cut off the head of a king that we don't talk about) the tradition of the British system of government was perhaps more stable and secure. If political systems have been in place for a long time, they are more likely to last for a long time.

Revolution or Reform?

|

Blackadder true or false quiz.

|

|

Just because the political system of Britain was more liberal and more modern than other continental systems at the start of the 19th century, it doesn't mean there wasn't pressure for further political change. As the Blackadder quiz will have demonstrated, there was plenty about the political system at the start of the 19th century that needed change. As we have seen, the industrial revolution was transforming Britain much more quickly than any other European country. The economic transformation and resulting social changes meant that a political system that was designed to protect the interests of landowners in a largely rural country was increasingly obsolete. What's more, the radical liberal and democratic ideas unleashed by the American and French revolutions (remember Tom Paine?) had not gone away.

|

The democracy problem. Edmund Burke is also mentioned in the film above as a celebrated opponent of democracy. The great fear of the social and economic elites in the 19th century was that political reform would eventually lead to democracy and the excesses of the French Revolution. For Burke and people like him, giving democratic power to the people - the ‘swinish multitude’ - risked doing irreparable damage to the country. Of course, today we consider democracy to be the only legitimate form of government. So why did the elites of Europe fear what democracy might do? Watch my film on the right to find out. |

In fact, as we will see in the next unit, (Matu 5) the European continent was subject to a series of political revolutions which periodically brought the old older crashing down. The threat of revolution in Britain was a serious possibility in Britain in the first half of the 19th century and many British conservatives following the ideas of Edmund Burke believed that the best way to avoid revolution was to gradually reform the social and political system: as Burke famously argued 'to reform in order to conserve'. It is not a coincidence that many of the most significant reforms in the Britain in the 19th century happened around the time of the great continental revolutions of 1830 and 1848. The Timelines.tv film opposite outlines the debate between the ideas of Tom Paine and those of Edmund Burke.

|

|

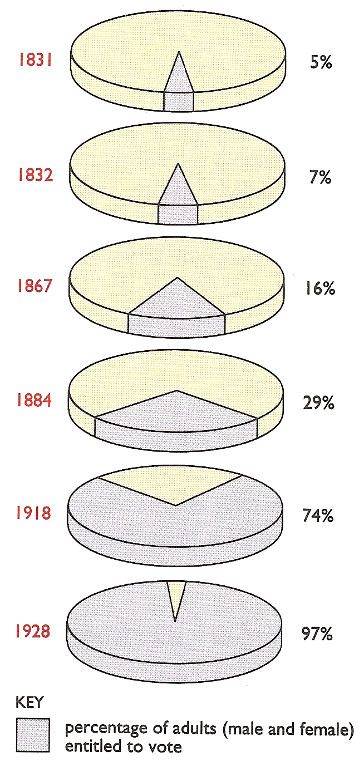

Part 1 - Politics and the middle classes

As we have seen in previous lessons, as industry developed so also did new social classes. The new industrial middle class began to ask, ‘why should these aristocrats decide everything just because they own lots of land’? You will have seen these ideas in the Enlightenment and as inspiration for the American and French Revolutions. The new middle classes were often very rich and powerful locally but wanted changes to the way in which the country was run nationally. The ideology that appealed to this group was liberalism. They wanted government to recognise the interests of business, not just agriculture. They wanted those who governed to be people who deserved to rule on merit, not simply because their parents had ruled before them. In order for this to happen, the political and electoral system needed to be changed. This gradual process of extending the franchise (the right to vote) began with one of the most important political events of the 19th century. The Great Reform Act of 1832 Before the 1832 Act one adult (aged over 21) man in ten could vote; after it, one adult man in five. The new voters were the fairly wealthy farmers in the countryside, and the middle classes in the towns. There were still only 650,000 voters out of a total adult population of about 14 million. Both before and after 1832 the right to vote depended on how much property a man owned. And of course Women could not vote at all. Many big landowners opposed reform because they were worried about losing power. But fear of revolution (in 1830 there were revolutions throughout Europe - Matu 5) and riots in England (see image of the Bristol riots below) helped force through the reform. It took two further Reform Acts (see right and 'Dawn of Democracy' film below) in the nineteenth century, and two in the twentieth, before this right was held by all adults, men and women. Having won the right to vote, the newly enfranchised middle classes began to weaken the control of the British aristocracy. New laws were passed which benefitted industry rather than landowners (cf. The Corn Laws repeal of 1846) |

By the middle of the 19th century, a modern two-party system had been created. The Liberal Party represented the interests of change and modernisation and the Conservative Party represented a desire to conserve all that was valuable in the British tradition. But what about the workers?

Activities 1

You should begin by carefully reading the text and watching the videos above. We are lucky that Royal Holloway's HistoryHub is currently producing lots of relevant short videos.

You should begin by carefully reading the text and watching the videos above. We are lucky that Royal Holloway's HistoryHub is currently producing lots of relevant short videos.

- Explain how and why the political system in Britain was different to that of mainland Europe in 1750. There are two aspects to this, so make sure you explain both clearly.

- Using our Blackadder discussion to help you, outline some of the criticisms that might have been made of the British political system by by radicals in Britain in c1800.

- Explain what Burke meant by 'to reform in order to conserve' and also explain why he, like many members of the elite, opposed the introduction of democracy. You need to watch my fantastic film to understand this fully.

- What was the ‘Great Reform Act’ and why was it so important given that it appeared to do so little.

Part 2 - Politics and the working classes

If there was one thing that middle-class liberals and aristocratic conservatives had in common it was their fear of the working classes. The workers had become the largest social group in England and were growing all the time. It was feared that in a democracy the workers would become the masters. It is not a coincidence that the Great Reform Act was passed at a time when Europe was undergoing a series of revolutions from 1830-1. The hope of conservatives who supported the Great Reform Act was that it would prevent revolution, ‘reform, that you may preserve’.

1810-1831: Britain on the verge of revolution?

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars until 1831, Britain gave every sign of being close to revolution. In the new industrial heartlands organised gangs of artisans destroyed the new industrial machinery that was putting them out of work. These Luddites’ violent actions were a general form of protest against a society that denied them a right to vote or organise. Trade Unions were not legalised until 1871. In the countryside, farm labourers took similar action in the Swing Riots of 1830, destroying the threshing machines that took away their traditional harvest jobs.

If there was one thing that middle-class liberals and aristocratic conservatives had in common it was their fear of the working classes. The workers had become the largest social group in England and were growing all the time. It was feared that in a democracy the workers would become the masters. It is not a coincidence that the Great Reform Act was passed at a time when Europe was undergoing a series of revolutions from 1830-1. The hope of conservatives who supported the Great Reform Act was that it would prevent revolution, ‘reform, that you may preserve’.

1810-1831: Britain on the verge of revolution?

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars until 1831, Britain gave every sign of being close to revolution. In the new industrial heartlands organised gangs of artisans destroyed the new industrial machinery that was putting them out of work. These Luddites’ violent actions were a general form of protest against a society that denied them a right to vote or organise. Trade Unions were not legalised until 1871. In the countryside, farm labourers took similar action in the Swing Riots of 1830, destroying the threshing machines that took away their traditional harvest jobs.

|

|

|

In 1831 in the iron town of Merthyr Tydfil in south Wales, hundreds of workers seized control of the town and raised the red flag of working class revolution for the very first time. The most significant event in this period happened just over 200 years ago and has been subject to recent Mike Leigh film. The Peterloo Massacre took place in St Peter’s Field, Manchester in August 1819. A peaceful demonstration of 60,000 people demanded a reform in the political system as a means of improving the social conditions of the workers. The meeting was broken up by a cavalry charge that left 14 men and women dead and hundreds injured.

|

|

|

|

Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many—they are few!

Shelley - The Masque of Anarchy

A poem written in response to Peterloo

Utopian socialism

For some, reforming the industrial system was never going to be enough and gaining the vote would make no difference. Some reformers wanted to replace capitalism with a system controlled by the workers themselves and run in the interests of all, not just the owners of industry (capitalists). In France, Fourier (1772-1837) and Saint-Simon (1760–1825) developed ideas that imagined alternative societies in which the nefarious influence of capitalism was removed. In Britain it was the Welsh industrialist Robert Owen who was most influential ‘utopian socialist’. Owen is best known for his efforts to improve the working conditions of his factory workers and his promotion of experimental communities for which he coined the word ‘socialism’. In 1824, Owen travelled to America, where he created an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana, the preliminary model for Owen's utopian society. The experiment was short-lived, lasting about two years. (See Matu 8, Lesson 4)

For some, reforming the industrial system was never going to be enough and gaining the vote would make no difference. Some reformers wanted to replace capitalism with a system controlled by the workers themselves and run in the interests of all, not just the owners of industry (capitalists). In France, Fourier (1772-1837) and Saint-Simon (1760–1825) developed ideas that imagined alternative societies in which the nefarious influence of capitalism was removed. In Britain it was the Welsh industrialist Robert Owen who was most influential ‘utopian socialist’. Owen is best known for his efforts to improve the working conditions of his factory workers and his promotion of experimental communities for which he coined the word ‘socialism’. In 1824, Owen travelled to America, where he created an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana, the preliminary model for Owen's utopian society. The experiment was short-lived, lasting about two years. (See Matu 8, Lesson 4)

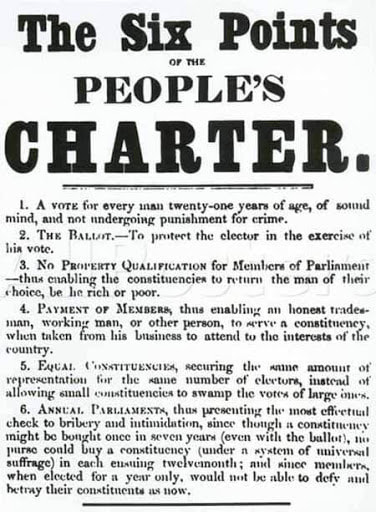

The Chartists

The Chartists were the supporters of 'The People's Charter', which made six demands for the reform of Parliament. The most important demand was that every man over the age of 21 should have the right to vote. As we have seen, working class living and working conditions were bad. Many believed that parliament had the power to change things for the better. They wanted to be able to elect MPs who understood their lives and who would do something to improve them.

The Chartists were the supporters of 'The People's Charter', which made six demands for the reform of Parliament. The most important demand was that every man over the age of 21 should have the right to vote. As we have seen, working class living and working conditions were bad. Many believed that parliament had the power to change things for the better. They wanted to be able to elect MPs who understood their lives and who would do something to improve them.

|

In 1839 a rising took place in Newport, south Wales in support of the Charter. It was the last large-scale armed attempted revolution in Great Britain, 22 demonstrators were killed when troops opened fire on them. The leaders of the rebellion were transported to Australia. Chartists generally used peaceful means, but each time they presented their Charter, Parliament refused to consider it.

|

|

In 1848 the Chartist leader, Feargus O'Connor, announced that over six million people had signed a new petition.

At a time of revolution throughout Europe, the British authorities feared that something similar might happen in Britain. Soldiers and extra police were employed, and the Chartists’ demands were ignored. In 2015 the Welsh actor made a documentary for the BBC about Chartism and the Newport Rising in particular. The film opposite is a short extract from the introdution. The full documentary can be seen here. |

|

Trade unions

By the 1870s skilled craftspeople such as carpenters, textile workers and bricklayers had succeeded in forming strong unions that were accepted by both employers and the government. They were expensive to join, and only well-paid skilled workers could afford the subscriptions. In return they provided important benefits such as unemployment pay, sick pay and old age pensions. In the 1880s nonskilled workers began to form 'new unions'. As we have seen in previous lessons, improved levels of literacy, improved communications and large concentrations of workers living together in the rapidly growing towns helped make this possible. The new unions had low subscriptions and aimed to improve their members' pay and working conditions. Unlike the old craft unions, they were prepared to take strike action. In 1888 the matchgirl workers at Bryant and May's factory in London held a successful strike for better wages and conditions of work. Successful strikes helped to increase union membership. In four years, between 1888 and 1892, it grew from 750,000 to 1.5 million.

By the 1870s skilled craftspeople such as carpenters, textile workers and bricklayers had succeeded in forming strong unions that were accepted by both employers and the government. They were expensive to join, and only well-paid skilled workers could afford the subscriptions. In return they provided important benefits such as unemployment pay, sick pay and old age pensions. In the 1880s nonskilled workers began to form 'new unions'. As we have seen in previous lessons, improved levels of literacy, improved communications and large concentrations of workers living together in the rapidly growing towns helped make this possible. The new unions had low subscriptions and aimed to improve their members' pay and working conditions. Unlike the old craft unions, they were prepared to take strike action. In 1888 the matchgirl workers at Bryant and May's factory in London held a successful strike for better wages and conditions of work. Successful strikes helped to increase union membership. In four years, between 1888 and 1892, it grew from 750,000 to 1.5 million.

|

|

|

|

|

The Labour Party

The members of the New Unions wanted Parliament to help them in their struggles against employers, and to provide the working class with better houses, and schemes for unemployment and sickness benefit. But both the Liberals and Conservatives supported the employers’ right to be free to run their businesses as they liked. In the 1890s people became convinced that a new party was needed, independent of both the Conservatives and the Liberals, to put up working-class candidates in elections. In 1900 the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) was established to organise Labour candidates for the next election. In the election of 1906, the LRC won twenty-nine seats and renamed themselves the Labour Party. Their first leader was Keir Hardie (right), their current leader Keir Starmer was named after him. |

|

|

|

Activities 2 - The political consequences of the industrial revolution for the working class

Design a timeline to show the significant events (bold) in the political response of the history of the working class in 19th century Britain. Is it correct to argue that most working-class movements failed?

Design a timeline to show the significant events (bold) in the political response of the history of the working class in 19th century Britain. Is it correct to argue that most working-class movements failed?

If you're looking for a challenge, have a go at creating a timeline using Knightlab. Below is Sydney's version from 2020.

Remember you need a Google account. The instructions are here. Download this spreadsheet and 'file - make a copy' and rename to your computer/iPad. Edit the various sections using the information on this website. You can easily add images (copy and paste image address) and video (just paste in YouTube link) and there are a range of formatting options. When complete, share the link with me on your class OneNote.

|

A final thought

Watch this last short film from Timelines.tv. It reflects on a century of change in a way that echoes our introductory unit on warfare last year. We made a comparison between the memorials of the Napoleonic war and the Battle of Solferino. The memorials of the First World War reflected the significant democratic changes of the 19th century. Other revision sources BBC Bitesize on protest in the 19th century and how and why Britain become more democratic. |

|