Lesson 7 - The end of the Cold War - internal and external factors

The Cold War started and ended in Europe. The Cold War came to an end because the communist states of central and eastern Europe collapsed in the autumn of 1989. These same states had faced previous crises in 1956 (Poland and Hungary), 1968 (Czechoslovakia) and 1981 (Poland) but the system had survived previously because of what become known as the Brezhnev doctrine . In 1988 the leader of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev introduced a new doctrine which he jokingly called the Sinatra Doctrine. When confronted with independent political movements in central and eastern Europe he didn't send in the tanks, he said these countries could decide for themselves how to reform their socialist systems. They could do it 'their way'. So, they did.

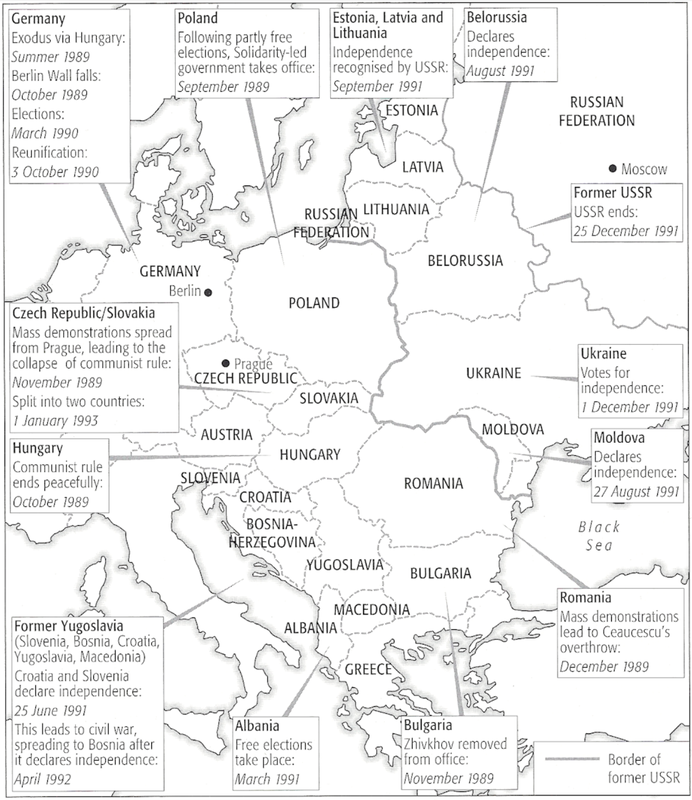

The communist states collapsed as a result of both external and internal factors. Internal factors were the problems faced by the communist states, including the USSR, within their own borders. Economic and political crises were common to all these states but dealt with in a variety of different ways with different consequences. The peaceful transfer of power of Poland and the Velvet Revolution of Czechoslovakia, were in stark contrast to the violent overthrow of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania or the genocide at Srebrenica which was a result of the post communist civil war in Yugoslavia. The external factors were the changing international relations of the Cold War that resulted from the rise to power of Gorbachev in 1985. Making a significant break with previous leaders, Gorbachev surprised the world and US President Reagan with a series of bold reforms which rewrote Soviet foreign policy.

|

External factors

a) The Second Cold War - Reagan's systematic challenge In 1980 Ronald Reagan representing the New Right in the USA was elected president. Reagan decided to increase the strength of the US army and put the Soviets under pressure. In 1983 he introduced the idea of a new defence system, the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI) or Star Wars. The Soviets were facing major problems. Solidarity in Poland (see below), war in Afghanistan and Reagan's challenge all led to the Second Cold War. In the USSR the economy was stagnating and the old leadership had no solutions to the problem. Between 1982 and 1985, three ageing Soviet leaders passed away: Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko. |

|

|

|

Even though the US economy suffered from a recession, the 1982 military budget was increased by 13%. It was decided that the USSR should be exposed to a ‘systematic challenge.’ New weapons should be developed which would be difficult to counter for the Soviets. New weapons would make Soviet weapons obsolete (out of date), which would put pressure on the Soviet economy. The Reagan administration started the largest peacetime military build-up in US history. Between 1981 and 1988 military spending went from $117 billion per year to $290 billion.

In 1983 Reagan announced his Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI) better known as the ‘Star Wars’ project. The aim was to develop a totally new and expensive technology, a shield protecting the USA in space. The same year Reagan gave a speech to the National Association of Evangelical Christians. The Soviet Union was described as an ‘evil empire’. (see film below) |

In November 1983 NATO started the deployment of the Pershings and the Cruise missiles. The USSR responded by pulling out from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) talks and Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (START) negotiations. On November 2, 1983, as Soviet intelligence services were attempting to detect the signs of a nuclear strike, NATO began to simulate one. The exercise, codenamed Able Archer was believed by some of the Soviet leadership that the exercise might have been a cover for an actual attack. The elderly leadership in the Kremlin who still remembered Hitler’s surprise invasion in 1941 was determined not to get caught out again. The Soviet Union, believing its only chance of surviving a NATO strike was to pre-empt it, readied its nuclear arsenal.

|

|

|

b) Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev was elected General Secretary at the age of 54 after the death of Chernenko in March 1985. He was the youngest member of the politburo and the first Soviet leader to be born in the Soviet Union rather than in Tsarist Russia. He had been university educated and made his career in the post-Stalin era. It was a remarkable change of generation. Old hardliners and former Stalinists like Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko had now been replaced by an open-minded optimist and reformer. This drastic change of attitude can be best illuminated by how traditional Soviet political jokes developed. During the stagnation, the Brezhnev years, you could tell jokes about the leaders in private, but never in public:

‘Two men were standing in a queue, trying to buy some food — an inevitable part of daily life in the USSR. One of them said: what's wrong in our country? Why do we always have to queue for daily food? His friend said: It's our leaders' fault. They are responsible. His friend said: I’ll make them responsible. I shall go and shoot them!

After two hours he came back. What happened, his friend in the queue asked? Well, I gave up. The queue was longer there’

What is remarkable about this joke is that it was told by Gorbachev - on television. In 1986 he introduced his Perestroika or reconstructing policy, indicating that far reaching economic reforms were needed (see films below). And under Glasnost political parties and organisations were allowed. Censorship was abolished in 1988. Gorbachev's new openness was necessary for Perestroika.

|

|

|

But it soon led to problems. When his reforms were accompanied by a severe economic crisis, the system collapsed. It became evident that republics within the Soviet Union and the satellites in Eastern Europe were not satisfied with only decentralised power and democracy without independence. In 1988 Gorbachev announced in the UN that every nation had the right to choose its own government i.e. a rejection of the Brezhnev doctrine. It didn't take long until both republics within the USSR, like the Baltic States, and the satellites in Eastern Europe demanded real independence. There were 15 republics and more than 120 ethnic groups within the USSR and freedom of speech released decades of bitterness over Stalin's repression and terror. Nationalist feelings led to Soviet control of Eastern Europe coming to an end in the autumn of 1989. It also led to a number of republics within the Soviet Union becoming independent states. In 1991, the hardliners tried to overthrow Gorbachev. It was last attempt by the old communists to retain power. They were defeated but so were Gorbachev's attempts to keep the USSR alive. On December 31 1991 the USSR was disbanded and Gorbachev as General Secretary of the USSR was out of a job.

|

Internal factors.

In brief, the most important internal factor was that the consent of the governed in the communist bloc began to break down. People stopped believing that the communism was a future worth building towards. There were three distinctive internal factors to explain: economic stagnation, new dissident led 'anti-political' movements and the popular mass movement. |

|

|

a) Economic stagnation.

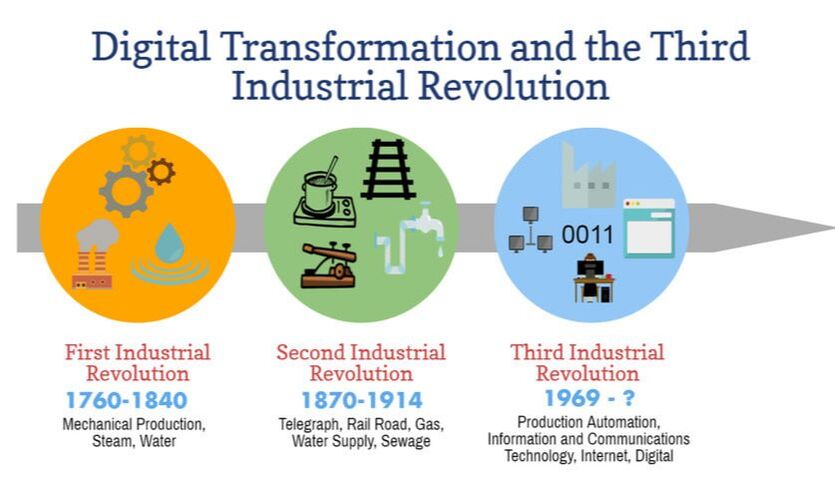

Brezhnev ignored the needs for reforms in the 1970s and 1980s. GNP growth had been around 10 % annually in the 1950s. It was 7 % in the 1960s and fell to 5% in the 1970s. In the early 1980s the growth was around 3 %. It was negative during the later Gorbachev era (-15 % in 1991). The planned command economy worked well enough in a Fordist era when a backward agricultural economy needed modernisation, but it couldn’t compete with post-Fordism and the 3rd industrial revolution. When after the Oil Crisis of 1973 western capitalism began to shift to a more consumer driven, post-industrial economy that depended on technological innovation associated with microchips and the telecommunications revolution, the inflexible, command economy could not compete. |

A command economy cannot plan innovation anymore than an actor can improvise the words of Shakespeare. The Eastern Bloc did not and, more importantly, could not produce a Silicon Valley or entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. By the 1980s the technology used in the Eastern Bloc was rapidly becoming out of date. The USSR was slow to develop new technologies, such as personal computers, robotics and video equipment. In the mid-1980s there were 30 million personal computers in the US and only 50,000 in the USSR. On the borders of East Germany and Czechoslovakia, West German television stations could be received with images of life under capitalism. Western music, cinema and fashion also had some influence on the people of eastern Europe. The mass consumer society of the West provided a sharp contrast with living standards in the East. Not only did western-style capitalism seem more attractive, but the failure of socialism to provide the living standards expected was evident to more and more of those citizens living in eastern Europe.

|

b) The 'anti-political' movements

In the mid-1970s a new form of opposition group emerged at the same time as the Détente era Helsinki accords were stressing the importance of civil rights. The groups that emerged like The Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) in Poland and Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia were groups of intellectuals who produced uncensored journals and newspapers. They deliberately did not politicise their organisations by being openly critical of the political system or by calling for communism to be replaced. Instead they focused on protecting human rights, civil disobedience and passive resistance. They often used humour and highlighted the ridiculous nature of communist propaganda, but they did not directly confront the state.

|

|

The Underground Society and Anti-Politics

‘Instead of organising ourselves as an underground state, we should be organising ourselves as an underground society… Such a movement should strive for a situation in which the government will control empty shops but not the market, employment but not the means to livelihood, the state press but not the flow of information, printing houses but not the publishing movement, telephones and the postal service but not communication, schools but not education’. (Wiktor Kulerski)

The most significant anti-political movement to emerge in central and eastern Europe was the polish Solidarity trade union. Solidarity gave local groups a national focus; capable of providing a challenge to the state but self-consciously limiting the extent of that challenge.

|

This was the same anti-political message promoted by Charter 77. Solidarity eschewed not only violence but also antagonistic, overtly political methods. Their leader Lech Wałęsa even issued six ‘commandments’, including the injunction ‘to keep peace and order’. In other words, Solidarity did not challenge the state, rather it wanted in the words of Andrzej Gwiazda ‘a moral revolution’ not a political one. This meant not choosing between revolution and compromise but rather undermining the state by ignoring it. This did not require an organised, centralised opposition but rather localised, personal resistance. When the time was right in the late 1980s it would be leaders of the anti-political movement who replace the communists and ensure a peaceful transition of power. |

|

|

|

c) Popular mass movement.

By the 1970s, citizens of central and eastern Europe had become accustomed to economic growth, health and welfare provision (baby boomers) that when threatened produced serious political grievances. The communist regimes could only dig themselves out of trouble by short term economic measures such as unsustainable wage increases which hastened them into long-term structural crisis. This was the vicious circle which characterised the periodic economic crisis and political reform in Poland. The regimes also produced higher expectations from its citizenship and the high quality, universal education system, provided the citizenship with the means of articulating it. Communism, to borrow a phrase from Marx, had created its own grave diggers. This was a citizenship that in 1980s was aware of the superiority of western consumer goods and the corrupt inefficiencies of the Soviet system. |

|

But as we saw in Lenin's remark in 1917, revolutions need revolutionaries, people who are willing to die for a better world to be born. Many of the historical narratives of 1989 ignore the risks taken by those who protested on the streets. It is worth remembering that in the summer of 1989 the Chinese Communist Party crushed the pro-democracy movement with tanks. Those who took to the streets in Leipzig and Prague, Warsaw and Budapest did not know, as we now do, that Gorbachev would both keep his word and stay in power. (see video below)

|

Activity

You have only one thing to do on this topic but make it a good one. Following the internal/external structure provided above and selecting evidence from the films, Prezis and timeline to support your answer, plan a seven minute oral exam presentation that answers the key question 'why did the Cold War come to an end?'.

You have only one thing to do on this topic but make it a good one. Following the internal/external structure provided above and selecting evidence from the films, Prezis and timeline to support your answer, plan a seven minute oral exam presentation that answers the key question 'why did the Cold War come to an end?'.

Extras and extension.

|

|

|

Adam Curtis is one of the most important documentary film makers in the world today. In 2022 he produced the seven part TraumaZone which deals with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the failure of Russia to maintain democracy in the 1990s.

Using no narration and just the occasional title, he tells his story through unused BBC archive footage which 'speaks' directly to the viewer. It takes a few moments to get into it, but the effect is a remarkable, visceral, felt understanding of why everything went wrong. |

|