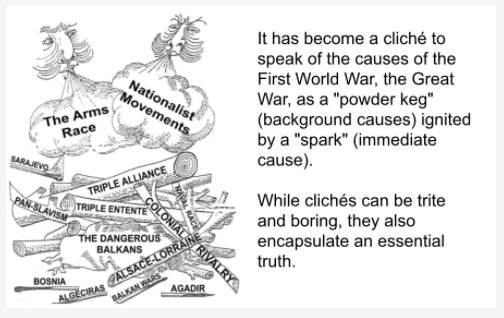

Matu syllabus reference - La 1re guerre mondiale : discuter des diverses causes de la première guerre et des questions relatives à la responsabilité de la guerre. Présenter les grandes étapes et les caractéristiques de la guerre ; mesurer les conséquences de la guerre, les buts et les limites des traités de paix et présenter la SDN comme espoir de sécurité collective. Matu syllabus

|

This unit features in the IB DP syllabus as Topic 11. Causes and effects of 20th-century wars. It is the first of a number of wars that we will be covering in S1-S3. This IB unit also draws upon the work that we covered last year in Year 11 as Warfare: A study through time.

Students who wish to be considered for the Moser Double Diploma will be encouraged to complete additional assignments in this unit. |

Revision

|

A4 Revision essentials is a printable but not editable A4 sheet with the absolute essentials to hopefully help you pass the Matu.

'Six like Sydney' is from the notes of a very successful former student. These are often more detailed than the website and might be edited to create your own notes. |

Films and extension materials.

There have been a number of significant documentaries and documentary series produced about World War 1 and the recent 100 year anniversary added significantly to that.

There have been a number of significant documentaries and documentary series produced about World War 1 and the recent 100 year anniversary added significantly to that.

|

|

BBC - Great War 1964

Very much a product of its time with all the flaws you'd expect both historical and technical but... I love the very literary approach that uses poetry and memoirs to convey the experience of war. In addition, the interviewed eyewitnesses were still relatively young men when the series was made and this somehow makes their testimony more immediate and relevant. I have included individual episodes in the lessons that are particularly worth watching. Click here for the BBC guide to each of the 24 episodes. |

|

|

Channel 4 - The First World War 2003

Unlike the BBC series, I watched this on TV when it first came out. The First World War (2003) is a ten-part Channel 4 documentary television series surveying the history of World War I (1914-1918). It is based on the 2003 book of the same name by Oxford history professor Hew Strachan. This is a more contemporary account, more international and less focused on the Western Front. Click here for an episode outline. |

|

|

The Great War - Week by Week (from 2014)

I remember watching the previews of this before it started and thinking it was ridiculously ambitious. Releasing a video every week for the 4 years+ to cover every week of the war?! But they did it and have gone on to do some other really useful short films on various WWI themes such as artists or countries. Unlike the first two series listed above, I haven't watched all of these but key moments or battles of the war are well worth looking at. This playlist includes a series of films they consider to be essential. |

|

|

The Guardian's interactive guide to World War 1, 2014.

This was produced for the centenary of 1914. You can either watch the short - Matu friendly - films opposite or navigate your own way around using their interactve website. |

Matu 7 - End of Unit Test - Wednesday 28th February.

This end of unit test will be slightly different to earlier editions. There will be four questions in the style of an IBDP history Paper 1 (see our earlier work on Italy in 1830-48) and focused on only two lessons from this unit: Lesson 5 and Lesson 6.

This end of unit test will be slightly different to earlier editions. There will be four questions in the style of an IBDP history Paper 1 (see our earlier work on Italy in 1830-48) and focused on only two lessons from this unit: Lesson 5 and Lesson 6.

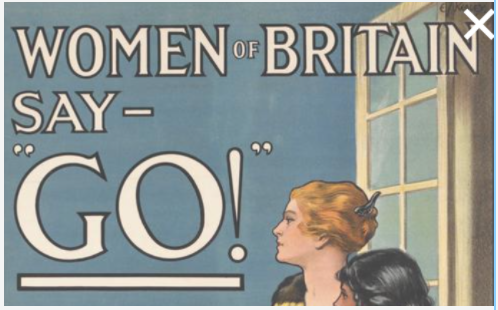

Question 1a tests your reading comprehension. Question 1b tests your ability to interpret an image or cartoon.

Question 2 requires you to find the Value and Limitations of a source with reference to Origin, Purpose and Content. (See films below)

Question 2 requires you to find the Value and Limitations of a source with reference to Origin, Purpose and Content. (See films below)

|

|

|

Question 3 tests your ability to compare and contrast the content of two sources. Remember you need to find similarities and difference between what the sources say.

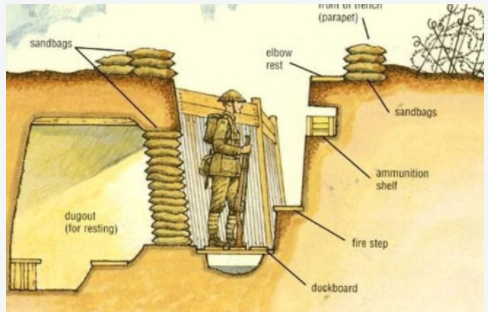

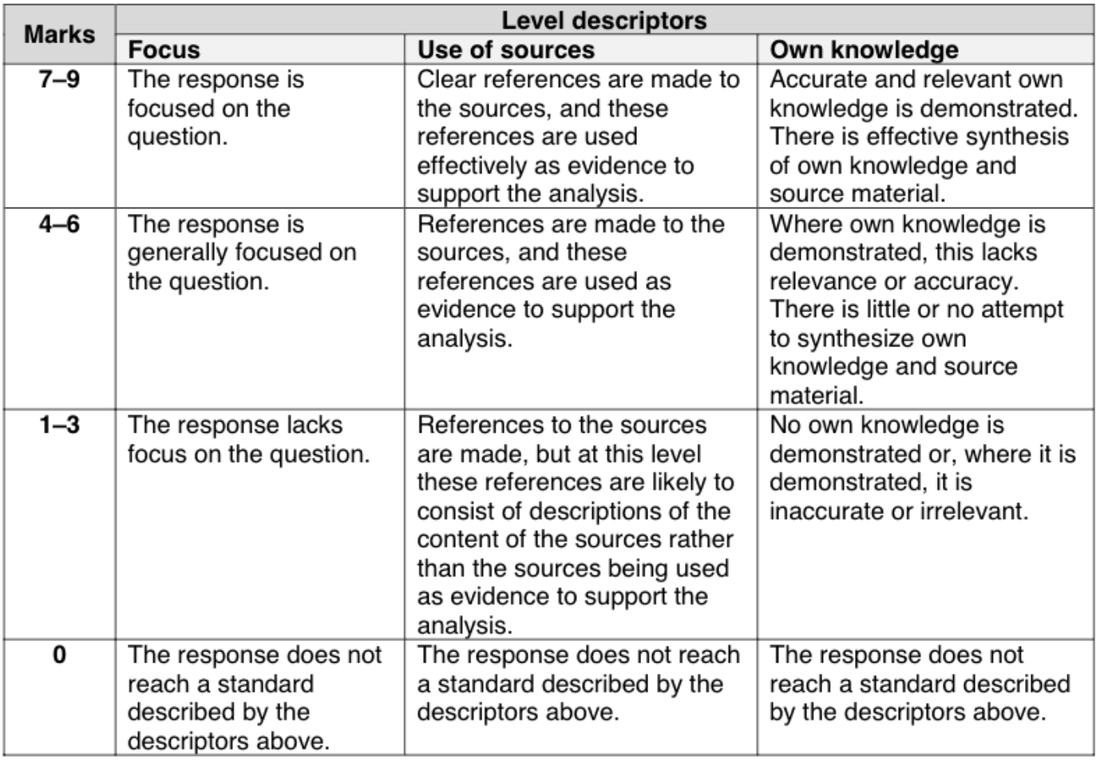

Question 4 will be this: “The First World War was the first 'total war' because the industrial revolution had transformed the very nature of warfare itself.” Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree with this statement?

Question 4 will be this: “The First World War was the first 'total war' because the industrial revolution had transformed the very nature of warfare itself.” Using the sources and your own knowledge, to what extent do you agree with this statement?

|

Remember this is a debatable synthesis question. It is debatable because (as we saw last year) it is not only technology which transforms the nature of war. It is a synthesis question because you have to synthesise the sources you are given (not necessarily all of the sources but at least two) with what you know in advance.

You should treat this like an essay. You should identify the big points (factors) that will form the first sentences of your paragraphs, explain these points and provide evidence/examples from the sources you are given and your own knowledge. Also remember to produce a brief introduction - which establishes your response to the question and what big points you are going to make - and a conclusion. The level descriptors of the left show how you will be assessed. |

In common with previous tests there will also be a quick 16 factual questions taken from the quiz below.

Click on the link to access the test.