This page provides a single stop for content that is found in various other parts of the website. The absolute essentials are in the PowerPoint below.

The Ancien Régime – Switzerland before 1789

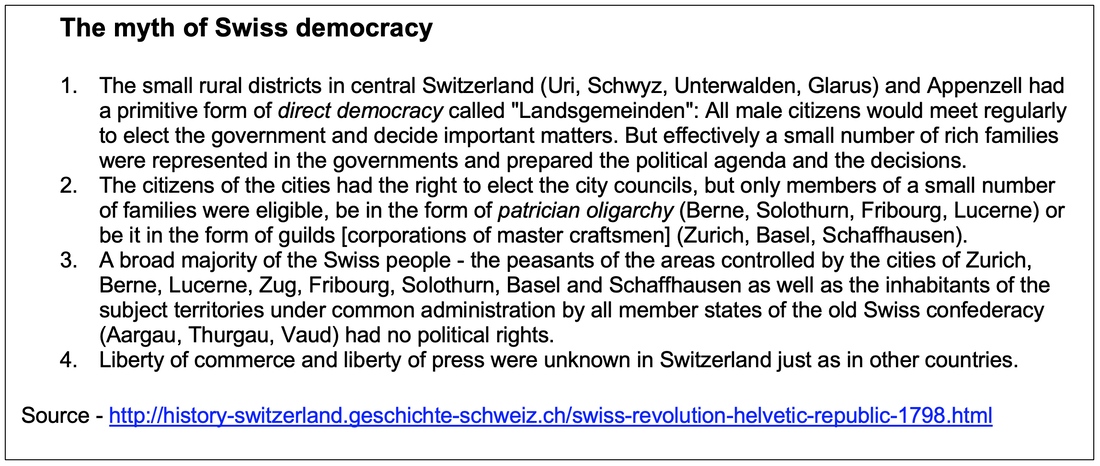

Switzerland is often considered to be one of the oldest democracies in the world. Apart from not giving all women the right to vote until 1971 in federal elections (1991 for the last canton), there is plenty of other evidence to illustrate that Switzerland’s historic democratic credentials are largely a myth.

Before 1798, Switzerland’s social and political system was characterised by the domination of a ruling, aristocratic class that was not dissimilar to pre-revolutionary France. As we have seen earlier this year, following the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 (which granted Swiss independence from the Holy Roman Empire) most European powers began a process of modernisation and centralisation of the political system. This did not happen in Switzerland, in part because she did not feel the need to, but also because her independence was much appreciated by other European powers. Swiss cantons provided mercenary soldiers to other European powers until the 19th century and in return the cantons received significant wealth and a recognised neutrality that was in everyone’s interest. So, despite deep internal divisions (notably between Catholic and Protestants), Switzerland gained a reputation for wealth and stability.

Switzerland before the French Revolution was a set of largely feudal states dominated by powerful oligarchies drawn from regionally important families. In fact, from the 17th century political representation became increasingly narrow, as important political positions were passed on from father to son, which had not been the case in previous centuries. Gradually, over time, individual rights and popular political participation declined as increasingly powerful families became absolute rulers.

Nor were all areas of the Old Swiss Confederacy equal. There were only 13 independent cantons, which along with Associate cantons, controlled vast areas of what would become modern-day Switzerland. For example, citizens of French speaking Vaud (which will play an important role in the 1798 revolution) had been under the control of German speaking Berne since the 16th century and its citizens enjoyed no political rights.

Nor were all areas of the Old Swiss Confederacy equal. There were only 13 independent cantons, which along with Associate cantons, controlled vast areas of what would become modern-day Switzerland. For example, citizens of French speaking Vaud (which will play an important role in the 1798 revolution) had been under the control of German speaking Berne since the 16th century and its citizens enjoyed no political rights.

The impact of the Enlightenment.

As in France, the political system in Switzerland came under increasing pressure for change throughout the 18th century, largely as a result of significant external forces. As we have seen, the Age of Enlightenment spread a range of new ideas about how society and government should work. Voltaire (who wrote Candide in Switzerland) and especially Geneva born Jean Jacques Rousseau, exercised considerable influence in Switzerland. Swiss society was becoming increasingly tolerant, executions for heresy and witchcraft stopped and the penal use of torture was increasingly criticised. The French Encyclopédie was published in Yverdon in the 1770s and Geneva, Lausanne and Neuchatel became important publishing centres that attracted intellectuals from all over Europe.

As in France, the political system in Switzerland came under increasing pressure for change throughout the 18th century, largely as a result of significant external forces. As we have seen, the Age of Enlightenment spread a range of new ideas about how society and government should work. Voltaire (who wrote Candide in Switzerland) and especially Geneva born Jean Jacques Rousseau, exercised considerable influence in Switzerland. Swiss society was becoming increasingly tolerant, executions for heresy and witchcraft stopped and the penal use of torture was increasingly criticised. The French Encyclopédie was published in Yverdon in the 1770s and Geneva, Lausanne and Neuchatel became important publishing centres that attracted intellectuals from all over Europe.

|

In addition, as we will see later, Switzerland became one of the first countries after Great Britain to be transformed by the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century. Agricultural reforms, the increasing use of the potato and better hygiene, led to a significant population increase. The development of spinning and weaving, the ‘putting-out’ system and improved roads gradually encouraged the development of a capitalist market economy. Rural families moved beyond a dependency on subsistence farming and increasingly generated income independent of agriculture.

|

|

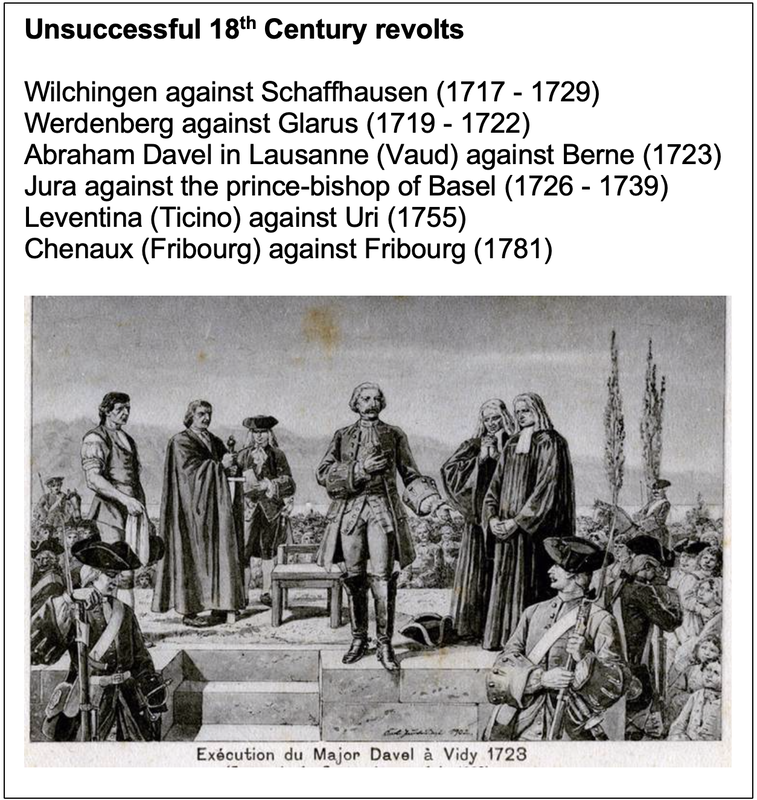

These cultural and economic forces made it increasingly difficult for the feudal oligarchies to resist reform and Switzerland became the scene of a string of attempted political revolutions throughout the 18th century.

For example, in March 1723 Major Davel the commanding officer of the Lavaux region marched on Lausanne and demanded an end to Bernese domination of Vaud and changes to how the deeply conservative Bernese church operated. He was beheaded. His death inspired later Vaudois 'patriots'. There is a statue of him in front of the Château Saint-Maire in Lausanne. (Right) |

|

In Geneva in 1762, the government ordered the burning of Rousseau’s Emile and Social Contract because of their subversive content. As a result, a new opposition movement was created to prevent government from censoring books without discussion. Although new rights were won in the short-term, many opposition leaders were ultimately forced into exile. In addition to the desire for political reform, by the end of the 18th century as in other European countries, many Swiss intellectuals began to think about about a Swiss national identity that might transcend regional cantonal differences. Franz Urs Balthasar's Patriotic Dreams inspired the creation in 1762 of the Helvetic Society which was to campaign for a unified Swiss state that would overcome the divisions between the cantons. The aims of the Society included a democratic reform of the Swiss constitution, and education for all, influenced by the ideas of Rousseau. The ideas behind the Helvetic Society will become increasingly important during and after the French Revolution which had an enormous influence on the future of the Swiss state. |

1789 – The impact of the French Revolution

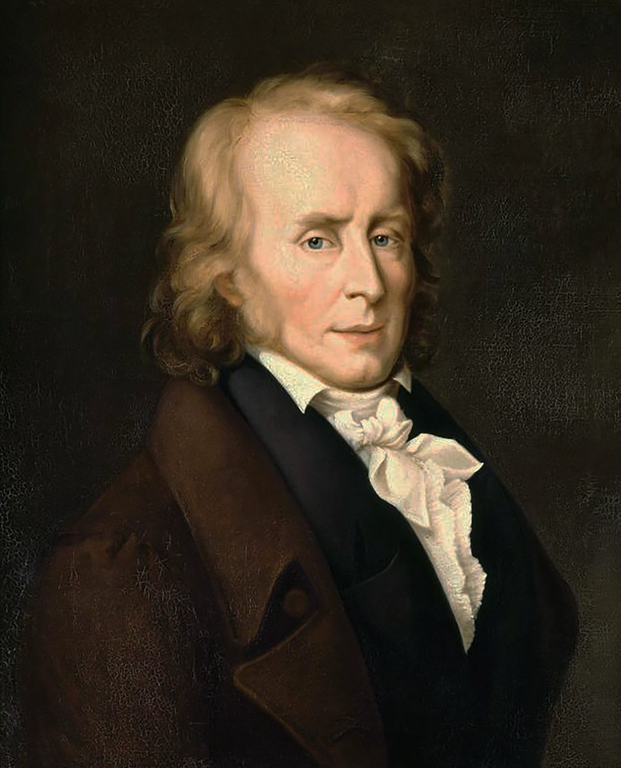

Initially the Swiss Ancien Régime was able to contain the influence of the French Revolution. For example, the Vaudois peasantry, like the peasants in the later European revolutions of 1830, had no rebellious traditions and often supported the Berne government. The most important developments were led by Swiss exiled intellectuals, who for example, formed the Club Helvétique in Paris in 1790. One of the most influential of these was Frédéric-César de La Harpe a lawyer from Rolle.

De La Harpe Island, Rolle, Vaud.

Born in 1754, Frédéric-César de La Harpe, was a brilliant student who gained his doctorate in law at the age of 20. He left Vaud in 1782 because of his opposition to the rule of the Gracious Lords of Berne. He ended up employed in the court of Catherine the Great of Russia who appointed him as tutor to her grandsons, including the future of Tsar, Alexander of Russia. This lifelong friendship resulted in the important support of Alexander I at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 in which Vaud retained its independence from Berne that had been established during the Napoleonic period. The artificial island was dedicated to La Harpe on his death in 1838, it contains a 13-metre-high obelisk built in his honour.

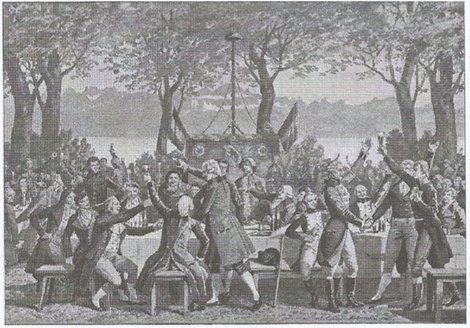

In Switzerland itself, the most significant support for the French Revolution was to be found in Vaud. Open-air political banquets were held to commemorate key events in the revolution. At Ouchy (see image and film below), Rolle and Vevey demonstrators waved the tricolour flag and wore revolutionary caps of liberty. They made toasts to the revolution and to Vaudois independence and petitioned the Berne government for tax cuts and political reform.

|

The response from Berne was typically counter-revolutionary. The government-imposed censorship and condemned La Harpe and his brother in their absence, but repression proved ineffective. Riots in Lausanne were followed later by clashes in Neuchatel and Geneva which appealed to France for support. In 1794 a revolutionary constitution was established in Geneva the canton was annexed and become part of France by 1798. In 1793 there was a revolt against taxes at Gossau (St. Gallen) and in 1794 in Stäfa (Zurich) peasants asked for the restauration of old political rights, granted by documents dating back to 1489 and 1532, that had gradually been eroded in the previous two centuries. |

When the French Revolution turned radical after 1792, (e.g. massacre of the Swiss Guards at the Tuileries palace in Paris) the conservative Swiss Confederacy broke with its traditional friendship with France and although it remained neutral in the European wars that followed, it readily welcomed fleeing French aristocrats and continued to resist domestic reform.

|

The French invasion of 1798.

In 1797 the French Directory staged a coup d’état in Paris. One of the leaders of the coup Reubell began discussions with La Harpe and Peter Ochs of Basel to consider the possibility of French intervention in Switzerland. France was interested in resources and access to Italy, La Harpe and Ochs were interested in implementing the political reforms of the Club Helvétique. In the end, the French invasion and the collapse of the Ancien Régime was quick and relatively bloodless. On 9 December 1797, Frédéric-César de La Harpe, asked France to invade Bern to protect Vaud. By February 1798, French troops occupied Mulhouse and Biel/Bienne. In Basel, ‘patriots’ drew up a new constitution and set up a first Swiss national assembly. |

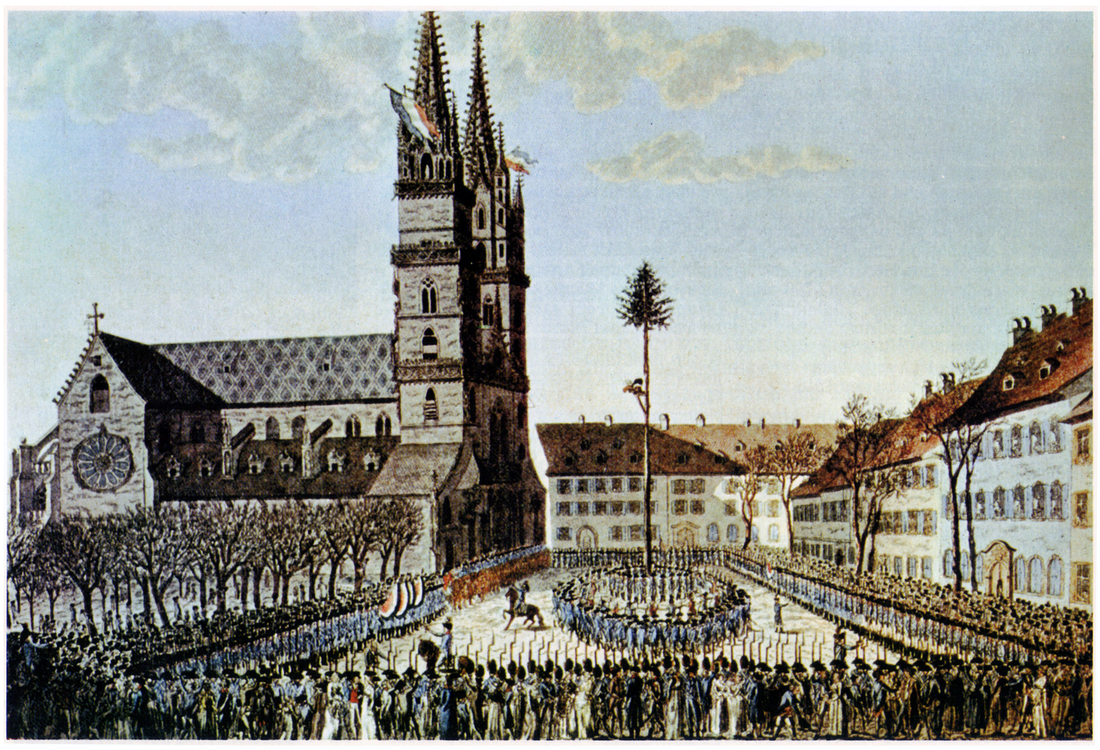

In Vaud, patriots seized Château Chillon and the Lemanic Republic was proclaimed. All over Switzerland thousands of liberty trees, often crowned with a ‘Tell Cap’, (See Basel opposite) were erected as symbols of support for the revolution. Importantly, all of these steps were supported by French troops. Throughout Switzerland revolutions and revolts toppled the governments of the Ancien Régime and abolished feudalism. The Confederation Diet broke up deeply divided and without taking any steps to prevent the French invasion. On 5 March, French troops entered Berne and the Confederation collapsed. By April the whole of the country was under French occupation.

Back in late 1797, it had been the young French general Napoleon Bonaparte who had pressed the French Directory to occupy Switzerland. Before we continue the story of the Swiss revolution we need to take a step back to look at the career of the Corsican military genius who would have such an impact of the history of Switzerland.

Back in late 1797, it had been the young French general Napoleon Bonaparte who had pressed the French Directory to occupy Switzerland. Before we continue the story of the Swiss revolution we need to take a step back to look at the career of the Corsican military genius who would have such an impact of the history of Switzerland.

The Helvetic Republic and Swiss Confederation 1798-1815

The Helvetic Republic (1798-1803)

121 representatives of the territories Aargau, Basel, Berne, Fribourg, Léman (Vaud), Lucerne, Oberland, Schaffhausen, Solothurn and Zurich met in Aarau on April 12th, 1798 to proclaim the Helvetic Republic and confirm its new constitution. The new régime abolished cantonal sovereignty and feudal rights. In its place, the French occupying forces established a centralised state based on the ideas of the French Revolution, a new tricolour flag and an official seal (with William Tell and a liberty tree).

The new constitution was not so much a democratic experiment, but rather more intended to make French control easier. The Helvetic Republic faced opposition from the very beginning from supporters of the Ancien Régime, Catholics who resented the revolutionary anti-religious (secular) policies and the cantons who had lost power. Resistance spread when new taxes were imposed, and French soldiers exploited the territory they occupied. And then in February 1799 Switzerland became the battle ground as France launched the War of the Second Coalition against Austria and Russia. Swiss soldiers were called up to fight for France, Swiss land and property was requisitioned and Switzerland was officially stripped of its neutral status.

121 representatives of the territories Aargau, Basel, Berne, Fribourg, Léman (Vaud), Lucerne, Oberland, Schaffhausen, Solothurn and Zurich met in Aarau on April 12th, 1798 to proclaim the Helvetic Republic and confirm its new constitution. The new régime abolished cantonal sovereignty and feudal rights. In its place, the French occupying forces established a centralised state based on the ideas of the French Revolution, a new tricolour flag and an official seal (with William Tell and a liberty tree).

The new constitution was not so much a democratic experiment, but rather more intended to make French control easier. The Helvetic Republic faced opposition from the very beginning from supporters of the Ancien Régime, Catholics who resented the revolutionary anti-religious (secular) policies and the cantons who had lost power. Resistance spread when new taxes were imposed, and French soldiers exploited the territory they occupied. And then in February 1799 Switzerland became the battle ground as France launched the War of the Second Coalition against Austria and Russia. Swiss soldiers were called up to fight for France, Swiss land and property was requisitioned and Switzerland was officially stripped of its neutral status.

|

The war severely weakened the Helvetic Republic. Its attempts to introduce radical reforms, to abolish tithes and feudal dues, lacked the resources to make it possible. And the leadership became increasingly divided. Firstly, La Harpe forced out Ochs and then La Harpe in turn was forced into exile after a failed attempted coup. Instability in the Republic reached its peak in 1802–03—including the Stecklikrieg civil war of 1802. A solution to the problem was finally forced on the Swiss by Napoleon who was by 1803 convinced that Switzerland was federal ‘by nature’. He imposed a ceasefire between the conservative Federalists and radical Unitarians and then a new constitution which was called the Act of Mediation. (See the 'interview' with Napoleon opposite!)

|

|

The Helvetic Republic had failed, but it had given Switzerland unity, national symbols, institutions and citizenship for the very first time. Importantly for places like Vaud, it had also expanded the number of independent cantons.

Swiss Confederation 1803-1815

The Swiss Confederation was re-established as a result of the Act of Mediation issued by Napoleon Bonaparte on 19 February 1803. It restored the 13 former cantons and added 6 more. There was also a Federal Diet. It was very much a compromise. There was no return to absolute rulers from before 1798, popular assemblies were restored and there were to be no privileged classes. But former rulers did return and most importantly, Switzerland remained a protectorate of France, bound by a military alliance and a requirement to provide soldiers for the French army.

The mediation period of the Swiss Confederation was a big improvement on the instability and war that had characterised the Helvetic Republic. Napoleon’s Continental System cut off British exports of textiles and encouraged the development of a domestic Swiss industrial capitalism. (See next lesson) Agriculture modernised and the Mediation governments encouraged public works. New national Swiss institutions were encouraged such as the Helvetic Society of 1807 and the Swiss folk games in Interlaken in 1805, which featured wrestling and yodelling. For the first time, Swiss patriotic identity extended beyond the educated elite.

But Switzerland was never fully independent at this time. 30,000 Swiss served in Napoleon’s Grand Army; some marines even served at Trafalgar. In 1806 the principality of Neuchâtel was given to Marshal Berthier. Ticino was occupied by French troops from 1810 to 1813. Also, in 1810 Valais was occupied and converted into the French department of the Simplon to secure the Simplon Pass. Napoleon regularly considered annexing the whole country, but as long as he ruled, the divisions between conservative federalists who wanted to restore the Ancien Régime and radicals who wanted to preserve their revolutionary gains, remained contained. As soon as Napoleon was weakened civil war threatened once again.

Congress of Vienna 1815

In December 1813 the Swiss Diet declared the end of Mediation regime. In some conservative cantons the old powerful families attempted to once again take power in. for example, Berne, Lucerne and Valais. But in other parts of Switzerland peasants demonstrated to defend their newly acquired rights. Civil War seemed likely, but under pressure from the Great Powers, notably the Russians, a new ‘Long Diet’ was established in order to make a new constitution. The Great Powers insisted that there would be no return to the past. The cantons created by Napoleon were to remain, Vaud for example retained its independence and three new cantons were added - Geneva, Neuchatel and Valais. In addition, the concept of a Swiss Confederation was formally used for the first time. The national Diet was to be responsible for trade, diplomacy and defence and a national Swiss army was created for the first time.

The Swiss Confederation was re-established as a result of the Act of Mediation issued by Napoleon Bonaparte on 19 February 1803. It restored the 13 former cantons and added 6 more. There was also a Federal Diet. It was very much a compromise. There was no return to absolute rulers from before 1798, popular assemblies were restored and there were to be no privileged classes. But former rulers did return and most importantly, Switzerland remained a protectorate of France, bound by a military alliance and a requirement to provide soldiers for the French army.

The mediation period of the Swiss Confederation was a big improvement on the instability and war that had characterised the Helvetic Republic. Napoleon’s Continental System cut off British exports of textiles and encouraged the development of a domestic Swiss industrial capitalism. (See next lesson) Agriculture modernised and the Mediation governments encouraged public works. New national Swiss institutions were encouraged such as the Helvetic Society of 1807 and the Swiss folk games in Interlaken in 1805, which featured wrestling and yodelling. For the first time, Swiss patriotic identity extended beyond the educated elite.

But Switzerland was never fully independent at this time. 30,000 Swiss served in Napoleon’s Grand Army; some marines even served at Trafalgar. In 1806 the principality of Neuchâtel was given to Marshal Berthier. Ticino was occupied by French troops from 1810 to 1813. Also, in 1810 Valais was occupied and converted into the French department of the Simplon to secure the Simplon Pass. Napoleon regularly considered annexing the whole country, but as long as he ruled, the divisions between conservative federalists who wanted to restore the Ancien Régime and radicals who wanted to preserve their revolutionary gains, remained contained. As soon as Napoleon was weakened civil war threatened once again.

Congress of Vienna 1815

In December 1813 the Swiss Diet declared the end of Mediation regime. In some conservative cantons the old powerful families attempted to once again take power in. for example, Berne, Lucerne and Valais. But in other parts of Switzerland peasants demonstrated to defend their newly acquired rights. Civil War seemed likely, but under pressure from the Great Powers, notably the Russians, a new ‘Long Diet’ was established in order to make a new constitution. The Great Powers insisted that there would be no return to the past. The cantons created by Napoleon were to remain, Vaud for example retained its independence and three new cantons were added - Geneva, Neuchatel and Valais. In addition, the concept of a Swiss Confederation was formally used for the first time. The national Diet was to be responsible for trade, diplomacy and defence and a national Swiss army was created for the first time.

The Industrial Revolution in Switzerland - Part 1 origins

Why was Switzerland one of the first countries to industrialise?

The industrial revolution began in the 1760s in Britain, then spread to the rest of Europe, first affecting northern France and Belgium, Switzerland, around 1800-1820. On the surface, there seem to be no obvious reasons why Switzerland should have been early to industrialise. Unlike the other countries, Switzerland has no obvious natural advantages. Mountainous and cut off from the sea, Switzerland does not have easy access to coal and iron reserves.

But Switzerland does have a geographically central location close to markets and other industrial centres, access to the Rhine, rivers to power factories and a culture of political liberalism, socio-cultural freedom and the Protestant tradition which had been important to the early develop of capitalism in the Netherlands and Britain. Towns like Geneva and Basel had long been renowned for their political and intellectual freedom, centres of learning and enlightened thinking.

In Switzerland, feudal restriction had been lifted to allow free movement of labour and self-governing urban centres existed with merchant capitalists ready to invest their money in new enterprises and technology. And perhaps most importantly, Switzerland was already an advanced European centre for the industry that kickstarted the Industrial Revolution: textiles.

Textile industry

Eastern Switzerland had been an important centre for textile (cloth) production since the end of the middle ages. In St. Gallen the ‘domestic system’ had been introduced in the 15th century. There was already a sophisticated division of labour with the ‘putting-out system’ where the work of skilled handloom weavers was supplied and distributed by a merchant capitalist class.

The production by machines in Switzerland began in 1801 in St. Gallen with the import of the latest machines from Great Britain. In Switzerland, hydraulic power was used instead of steam-engines because in the mountains and hills there is relatively easy access to waterpower. As early as 1814 the machines had replaced textile production by hand completely.

Mechanical Engineering

A second area of industrial innovation came with the development of machine manufacture. As we saw in a previous unit, France’s Continental Blockade attempted to isolate Britain from European trade during the Napoleonic Wars. In Switzerland, this meant that British industrial machinery could not be imported. This provided the incentive for Swiss textile manufactures to begin producing their own machines. 1805 Escher, Wyss & Co. (Zurich) and 1810 Johann Jacob Rieter & Co. (Winterthur) were amongst the first engineering companies to establish what became a rich industrial tradition in the north-east of Switzerland.

Watchmaking

The industry most associated with Switzerland is watchmaking and as with textiles, its origins are to be found in history that predates the industrial revolution. It was the freedom and religious toleration of Geneva that encouraged French Protestant (Huguenots) watchmakers to settle there in the 16th century. By the late 18th century, watch making had spread north to Neuchâtel. Around 1785 some 20,000 people worked in the watchmaking industry of Geneva and produced 85,000 watches per year, another 50,000 watches were produced in the region of Neuchâtel.

Chemical and food industries

The first chemical factory in Switzerland was founded by Daniel Frey at Aarau in 1804. The industry started to become important from the 1850s. In 1859 Alexandre Clavel, Louis Durand and Etienne Marnas came from France to Basel to produce synthetic colors. From 1884 their company was known as Chemische Industrie Basel (CIBA). Basel is still today a world centre for the chemical and pharmaceutical industry.

Chocolate was produced in Switzerland as early as 1803 by hand-crafted methods. In 1819 François-Louis Cailler founded his chocolate factory at Vevey. Advertising by Philippe Suchard (Neuchâtel 1826) made Swiss Chocolate known to the world. Daniel Peter (from Vevey) invented milk chocolate in 1875 and Rodolphe Lindt a new method to make chocolate melt on the tongue (not a sandy texture) in 1879. Industrialization created a market for products that could be prepared and eaten quickly, sometimes even during work at the factories. Maggi and Knorr were Swiss companies that created instant soups in cubes or bags. Henri Nestlé invented a food for babies based on milk, sweeteners and flour in 1866. His factory at Vevey became in 1905 became one of the first multinational food industries.

The industrial revolution began in the 1760s in Britain, then spread to the rest of Europe, first affecting northern France and Belgium, Switzerland, around 1800-1820. On the surface, there seem to be no obvious reasons why Switzerland should have been early to industrialise. Unlike the other countries, Switzerland has no obvious natural advantages. Mountainous and cut off from the sea, Switzerland does not have easy access to coal and iron reserves.

But Switzerland does have a geographically central location close to markets and other industrial centres, access to the Rhine, rivers to power factories and a culture of political liberalism, socio-cultural freedom and the Protestant tradition which had been important to the early develop of capitalism in the Netherlands and Britain. Towns like Geneva and Basel had long been renowned for their political and intellectual freedom, centres of learning and enlightened thinking.

In Switzerland, feudal restriction had been lifted to allow free movement of labour and self-governing urban centres existed with merchant capitalists ready to invest their money in new enterprises and technology. And perhaps most importantly, Switzerland was already an advanced European centre for the industry that kickstarted the Industrial Revolution: textiles.

Textile industry

Eastern Switzerland had been an important centre for textile (cloth) production since the end of the middle ages. In St. Gallen the ‘domestic system’ had been introduced in the 15th century. There was already a sophisticated division of labour with the ‘putting-out system’ where the work of skilled handloom weavers was supplied and distributed by a merchant capitalist class.

The production by machines in Switzerland began in 1801 in St. Gallen with the import of the latest machines from Great Britain. In Switzerland, hydraulic power was used instead of steam-engines because in the mountains and hills there is relatively easy access to waterpower. As early as 1814 the machines had replaced textile production by hand completely.

Mechanical Engineering

A second area of industrial innovation came with the development of machine manufacture. As we saw in a previous unit, France’s Continental Blockade attempted to isolate Britain from European trade during the Napoleonic Wars. In Switzerland, this meant that British industrial machinery could not be imported. This provided the incentive for Swiss textile manufactures to begin producing their own machines. 1805 Escher, Wyss & Co. (Zurich) and 1810 Johann Jacob Rieter & Co. (Winterthur) were amongst the first engineering companies to establish what became a rich industrial tradition in the north-east of Switzerland.

Watchmaking

The industry most associated with Switzerland is watchmaking and as with textiles, its origins are to be found in history that predates the industrial revolution. It was the freedom and religious toleration of Geneva that encouraged French Protestant (Huguenots) watchmakers to settle there in the 16th century. By the late 18th century, watch making had spread north to Neuchâtel. Around 1785 some 20,000 people worked in the watchmaking industry of Geneva and produced 85,000 watches per year, another 50,000 watches were produced in the region of Neuchâtel.

Chemical and food industries

The first chemical factory in Switzerland was founded by Daniel Frey at Aarau in 1804. The industry started to become important from the 1850s. In 1859 Alexandre Clavel, Louis Durand and Etienne Marnas came from France to Basel to produce synthetic colors. From 1884 their company was known as Chemische Industrie Basel (CIBA). Basel is still today a world centre for the chemical and pharmaceutical industry.

Chocolate was produced in Switzerland as early as 1803 by hand-crafted methods. In 1819 François-Louis Cailler founded his chocolate factory at Vevey. Advertising by Philippe Suchard (Neuchâtel 1826) made Swiss Chocolate known to the world. Daniel Peter (from Vevey) invented milk chocolate in 1875 and Rodolphe Lindt a new method to make chocolate melt on the tongue (not a sandy texture) in 1879. Industrialization created a market for products that could be prepared and eaten quickly, sometimes even during work at the factories. Maggi and Knorr were Swiss companies that created instant soups in cubes or bags. Henri Nestlé invented a food for babies based on milk, sweeteners and flour in 1866. His factory at Vevey became in 1905 became one of the first multinational food industries.

Switzerland 1815 – 1847 ‘Restoration’ and ‘Regeneration’

As in much of Western Europe, post-Napoleonic Swiss history follows patterns that are divided by the landmark dates of 1830 and 1848. Some of the structural pressures were also similar. Switzerland’s industrial growth was one of the most advanced in Europe and began to transform the country economically and socially. Political liberalism that demanded constitutional and representative government and a final end to restrictive feudal laws, continued to grow in influence. And Swiss nationalism, which was first important in the period before 1798, continued to spread out from the educated classes to all sectors of society. This historic time in Swiss history is traditionally divided into two periods: ‘Restoration’ refers to the period of 1814 to 1830 and the attempts to the restore the Swiss Ancien Régime (and cantonal authority) which reversed the changes imposed by centralist Helvetic Republic from 1798 and Napoleon’s compromise Act of Mediation of 1803. ‘Regeneration’ refers to the period of 1830 to 1848, when in the wake of the July Revolution in Paris, the Ancien Régime was challenged by the liberal and nationalist movement.

And yet although Swiss history appears to resemble wider European patterns at this time, there was something distinctly Swiss about the whole process of change. The forces of conservatism were not a simply a feudal class of landowning aristocrats clinging on to feudal traditions that supported a traditional way of life. In Switzerland there was a regional and religious dimension to the opposition to change that resulted in particularly deep divisions. There were to be revolutions all across Europe in this period, but only Switzerland had, in 1847, a genuine civil war.

1815–1830: Restoration.

As we have seen, the old elite ‘patricians’ and many of the ruling families returned to power as a result of decisions made at the Congress of Vienna. Switzerland was forced into supporting the Holy Alliance and this resulted in restrictions on the freedom of the press and an end to Swiss toleration of political refugees. However, almost from the beginning, the restored regimes faced challenges from reformers. As early as 1816, an economic depression caused by the return of Britain’s modern textiles industries to European markets, made life difficult for the Swiss traditional hand-loom worker. In addition, the Restoration regimes had reintroduced cantonal tolls and customs and restricted freedom of movement, all of which damaged trade. Opposition demanded political and economic reform. The Vaudois liberal Benjamin Constant (lover and protégé of Germaine de Staël) wrote influential texts calling for constitutional reform to follow the English model that were inspirational to liberals throughout Europe.

And yet although Swiss history appears to resemble wider European patterns at this time, there was something distinctly Swiss about the whole process of change. The forces of conservatism were not a simply a feudal class of landowning aristocrats clinging on to feudal traditions that supported a traditional way of life. In Switzerland there was a regional and religious dimension to the opposition to change that resulted in particularly deep divisions. There were to be revolutions all across Europe in this period, but only Switzerland had, in 1847, a genuine civil war.

1815–1830: Restoration.

As we have seen, the old elite ‘patricians’ and many of the ruling families returned to power as a result of decisions made at the Congress of Vienna. Switzerland was forced into supporting the Holy Alliance and this resulted in restrictions on the freedom of the press and an end to Swiss toleration of political refugees. However, almost from the beginning, the restored regimes faced challenges from reformers. As early as 1816, an economic depression caused by the return of Britain’s modern textiles industries to European markets, made life difficult for the Swiss traditional hand-loom worker. In addition, the Restoration regimes had reintroduced cantonal tolls and customs and restricted freedom of movement, all of which damaged trade. Opposition demanded political and economic reform. The Vaudois liberal Benjamin Constant (lover and protégé of Germaine de Staël) wrote influential texts calling for constitutional reform to follow the English model that were inspirational to liberals throughout Europe.

|

Benjamin Constant born in Lausanne in 1767, was one of the first political intellectuals to describe himself as liberal. He considered the British form of constitutional government as the best model for modern capitalist European states. Germaine de Staël was the daughter of Louis XVI’s banker Jacques Necker and was known for her literary salon in Paris and at Coppet. A proto- feminist who coined the word ‘romanticism’, it was said of her that there are three great powers in Europe: Britain, Russia and Madame de Staël.

|

Nationalists inspired by the success of the federal army called for more national institutions to be created. The Helvetic Society was revived and played a more political role. The example of the Greek independence movement inspired romantic nationalists in Switzerland as throughout Europe.

Although the Swiss movement for political reform predated the 1830 revolutions in Europe – successful pressure and petitioning for constitutional reform had resulted in limited reform in Lucerne and Schaffhausen and significant changes in Ticino – the July revolution in Paris was a catalyst for countrywide change. Faced with countrywide demonstrations the Diet recognised the right of cantons to change their constitutions and almost all did so. Historically this is known as the ‘Regeneration’.

1830-47: Regeneration

The Regeneration resulted in a swathe of classical liberal reforms being introduced across the Swiss cantons. The 1815 restoration of feudal privileges and economic restraints were removed, city walls were pulled down and legislative bodies were liberalised with wider representation. Cantonal executives had powers reduced and terms of office were limited, censorship was ended, and new constitutions became subject to approval by popular vote.

But the 1830 Regeneration did not resolve divisions in Swiss society. As with all revolutions and reform movements, there were divisions in the cantons between the reformers and conservatives and also within the reform movement itself. For example, in Basel in the 1830s, the rural population led by the lawyer Stefan Gutzwiller argued for fairer representation in the legislature. When their demands were rejected, they set up a Provisional Governing Assembly of their own in Lietstal.

The Basel authorities tried to break up the assembly by force but were beaten off in August 1831. The federal Diet sent soldiers to keep the two sides apart and allowed the creation of two half-cantons. The city finally accepted this division in August 1833, but only after suffering a series of military defeats in the preceding two years. A similar conflict also required federal intervention in Schwyz.

As well as divisions within cantons, there were also divisions between reformers. Many liberals were happy with the changes that had been implemented, but others wanted to go still further. Contemporaneous with the Chartist movement in Britain, these ‘advanced liberals’ or freisinnige radicals argued for the introduction of direct democracy and universal male suffrage, often as a means to improve living standards. In Switzerland, there was also an additional religious dimension, which saw the radicals calling for educational reforms intended to weaken the power of the Church. It was this religious conflict and strident and ultimately armed Catholic opposition to reform, which would ultimately push the Swiss cantons into civil war.

Although the Swiss movement for political reform predated the 1830 revolutions in Europe – successful pressure and petitioning for constitutional reform had resulted in limited reform in Lucerne and Schaffhausen and significant changes in Ticino – the July revolution in Paris was a catalyst for countrywide change. Faced with countrywide demonstrations the Diet recognised the right of cantons to change their constitutions and almost all did so. Historically this is known as the ‘Regeneration’.

1830-47: Regeneration

The Regeneration resulted in a swathe of classical liberal reforms being introduced across the Swiss cantons. The 1815 restoration of feudal privileges and economic restraints were removed, city walls were pulled down and legislative bodies were liberalised with wider representation. Cantonal executives had powers reduced and terms of office were limited, censorship was ended, and new constitutions became subject to approval by popular vote.

But the 1830 Regeneration did not resolve divisions in Swiss society. As with all revolutions and reform movements, there were divisions in the cantons between the reformers and conservatives and also within the reform movement itself. For example, in Basel in the 1830s, the rural population led by the lawyer Stefan Gutzwiller argued for fairer representation in the legislature. When their demands were rejected, they set up a Provisional Governing Assembly of their own in Lietstal.

The Basel authorities tried to break up the assembly by force but were beaten off in August 1831. The federal Diet sent soldiers to keep the two sides apart and allowed the creation of two half-cantons. The city finally accepted this division in August 1833, but only after suffering a series of military defeats in the preceding two years. A similar conflict also required federal intervention in Schwyz.

As well as divisions within cantons, there were also divisions between reformers. Many liberals were happy with the changes that had been implemented, but others wanted to go still further. Contemporaneous with the Chartist movement in Britain, these ‘advanced liberals’ or freisinnige radicals argued for the introduction of direct democracy and universal male suffrage, often as a means to improve living standards. In Switzerland, there was also an additional religious dimension, which saw the radicals calling for educational reforms intended to weaken the power of the Church. It was this religious conflict and strident and ultimately armed Catholic opposition to reform, which would ultimately push the Swiss cantons into civil war.

Switzerland 1847 - Sonderbund War

Towards civil war

As in the rest of Europe, what brought the underlying religious tensions to the surface was the economic depression of the 1840s. The Swiss economy had undergone significant change in the previous generation. Textile manufacture, machine tools and chemicals had grown so that one quarter of all Swiss now worked in manufacturing. But in the 1840s these industries were hit by recession. The economic slump created social problems with which the new industrial society struggled to cope. Socio-economic discontent fuelled a desire for a political response which inevitably brought to the surface polarising religious divisions.

In 1834, six regenerated liberal cantons agreed to the Articles of Baden which set new rules for seminaries (schools for priests), marriages and feast days which were strongly opposed by conservative Swiss Catholicism. In 1837 in Zurich, peasants marched against the liberal government and after 14 people were killed an anti-radical government was put in place. Joseph Leu of Ebersoll in Lucerne led Catholic activists in the struggle against radicalism, founding the Catholic Brotherhood to defend Catholic control of education and to allow Jesuits into Swiss education. Catholic conservatives also fought against radical reforms in Valais and Ticino.

In 1841, Augustin Keller a liberal, initiated the rewriting of the cantonal constitution of Aargau which weakened the position of Catholics. The pro-Catholic demonstrations and anti-Catholic government retaliation led the Catholic leadership to begin discussions about organising themselves militarily. In Valais, conservatives introduced a new constitution which excluded French speakers and banned Protestantism. In 1843, Josef Leu recalled Jesuits to Lucerne.

In response, liberal cantons became increasingly radical. In 1845 Henri Druey the leader of the National Association in Vaud overthrew the liberal government for not preventing Jesuit influence. Similar radical movements came to power in power in Ticino, Zurich and Berne. When radicals failed to overthrow the conservative government in Lucerne in 1845, thousands of radical volunteers (Freischarenzug) marched on the city on two occasions but were defeated and suffered hundreds of casualties (see image opposite).

In July 1845, a freischaren soldier murdered Catholic political leader Josef Leu. In response, in December 1945, seven Catholic cantons - Lucerne, Fribourg, Valais, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug – formed a secret security pact a ‘Sonderbund’ (special alliance). As soon as it became public, ten cantons called for its dissolution, but they lacked the majority in the Diet to force the law through. This majority was finally achieved in July 1847 and the Diet called for the breakup of the Sonderbund and the expulsion of the Jesuits. In response, the Sonderbund began preparing for war.

As in the rest of Europe, what brought the underlying religious tensions to the surface was the economic depression of the 1840s. The Swiss economy had undergone significant change in the previous generation. Textile manufacture, machine tools and chemicals had grown so that one quarter of all Swiss now worked in manufacturing. But in the 1840s these industries were hit by recession. The economic slump created social problems with which the new industrial society struggled to cope. Socio-economic discontent fuelled a desire for a political response which inevitably brought to the surface polarising religious divisions.

In 1834, six regenerated liberal cantons agreed to the Articles of Baden which set new rules for seminaries (schools for priests), marriages and feast days which were strongly opposed by conservative Swiss Catholicism. In 1837 in Zurich, peasants marched against the liberal government and after 14 people were killed an anti-radical government was put in place. Joseph Leu of Ebersoll in Lucerne led Catholic activists in the struggle against radicalism, founding the Catholic Brotherhood to defend Catholic control of education and to allow Jesuits into Swiss education. Catholic conservatives also fought against radical reforms in Valais and Ticino.

In 1841, Augustin Keller a liberal, initiated the rewriting of the cantonal constitution of Aargau which weakened the position of Catholics. The pro-Catholic demonstrations and anti-Catholic government retaliation led the Catholic leadership to begin discussions about organising themselves militarily. In Valais, conservatives introduced a new constitution which excluded French speakers and banned Protestantism. In 1843, Josef Leu recalled Jesuits to Lucerne.

In response, liberal cantons became increasingly radical. In 1845 Henri Druey the leader of the National Association in Vaud overthrew the liberal government for not preventing Jesuit influence. Similar radical movements came to power in power in Ticino, Zurich and Berne. When radicals failed to overthrow the conservative government in Lucerne in 1845, thousands of radical volunteers (Freischarenzug) marched on the city on two occasions but were defeated and suffered hundreds of casualties (see image opposite).

In July 1845, a freischaren soldier murdered Catholic political leader Josef Leu. In response, in December 1945, seven Catholic cantons - Lucerne, Fribourg, Valais, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug – formed a secret security pact a ‘Sonderbund’ (special alliance). As soon as it became public, ten cantons called for its dissolution, but they lacked the majority in the Diet to force the law through. This majority was finally achieved in July 1847 and the Diet called for the breakup of the Sonderbund and the expulsion of the Jesuits. In response, the Sonderbund began preparing for war.

|

Sonderbund War 1847

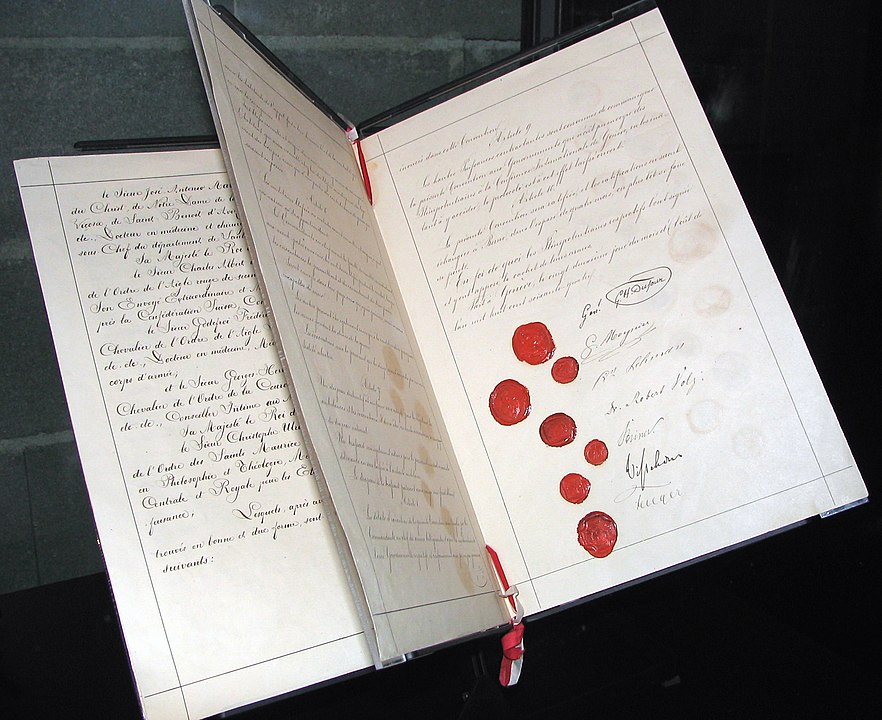

The Treaty of Vienna of 1815 had a guaranteed the right to intervene on any Swiss change to the constitution if they all agreed it was necessary. At this point, Austria and France were conservative Catholic powers and wanted to help the Swiss conservatives. Austria remained neutral but Britain favoured the liberal cause and wanted the Jesuits expelled. Consequently, there was no significant foreign intervention, and this undoubtedly helped the liberals. Colonel Jean-Ulrich de Salis-Soglio of Grisons was elected and sworn in as commander in chief of the Sonderbund army on 15 January 1847. He controlled an army of approximately 80,000. On 21 October 1847, the Federal Diet elected General Dufour of Geneva as commander in chief of the federal army. On October 24th, 1847 the Diet ordered the mobilisation of 50,000 men, although 100,000 signed up. |

|

The first major offensive took place in Fribourg in November which surrendered to the federal forces with little resistance. There was more significant resistance in Lucerne but the city also fell on November 27th. The other Sonderbund cantons surrendered and by the November 29th and after 27 days, the war was over. In all, 130 soldiers had been killed. The 20 million francs cost of the war was paid by the Sonderbund cantons and Neuchâtel and Appenzell Innerrhoden were also fined for not providing troops to the federal army. This was to the last armed conflict on Swiss territory until today.

|

Swiss Federal Constitution 1848

In 1848, a new Swiss Federal Constitution drafted by Johann Conrad Kern of Thurgau Henri Druey of Vaud, ended the almost-complete independence of the cantons and transformed Switzerland into a federal state. In the year of European revolutions only the Swiss succeeded in creating a democratic state. The Swiss drew up a constitution which was federal, much of it inspired by the American example. The new constitution created, for the first time, Swiss citizenship in addition to cantonal citizenship. This constitution provided for a central authority while leaving the cantons the right to self-government on local issues. The executive was the Federal Council, seven members elected by the Federal Assembly. |

|

The Federal Assembly was divided between an upper house (the Council of States, two representatives per canton) and a lower house (the National Council, with representatives elected from across the country). One of the first acts of the Assembly was to choose Berne as the federal capital. Referendums were made mandatory for any amendment of this constitution. This new constitution also brought a legal end to nobility in Switzerland.

A system of single weights and measures was introduced, in 1849 a federal postal service was introduced and in 1850 the Swiss franc became the Swiss single currency. A federal university and a polytechnic school were to be founded. The Swiss railway line was opened in 1847, connecting Zürich and Baden. In 1854 roads and canals were taken under federal control. Article 11 of the constitution forbade sending troops to serve abroad, with the exception of serving the Holy See. All Christians were guaranteed the exercise of their religion, but the Jesuits were expelled from Switzerland and this ban was only lifted on 20 May 1973. The constitutional basis for the modern Swiss state was in place.

A system of single weights and measures was introduced, in 1849 a federal postal service was introduced and in 1850 the Swiss franc became the Swiss single currency. A federal university and a polytechnic school were to be founded. The Swiss railway line was opened in 1847, connecting Zürich and Baden. In 1854 roads and canals were taken under federal control. Article 11 of the constitution forbade sending troops to serve abroad, with the exception of serving the Holy See. All Christians were guaranteed the exercise of their religion, but the Jesuits were expelled from Switzerland and this ban was only lifted on 20 May 1973. The constitutional basis for the modern Swiss state was in place.

The Industrial Revolution in Switzerland - Part 2 consequences

Railways

The development of the railways in Switzerland was relatively late. In the 1840s, individual cantons still imposed tariffs and tolls on people and goods that crossed their frontiers. The new federal constitution of 1848 enabled the planning and financing of railways and soon after there was rapid expansion with more than 1000km of line built in a 10-year period. By the time the federal government took over (nationalised) the railways in 1898, Switzerland had one of the densest railway networks in the world.

Socio-economic consequences

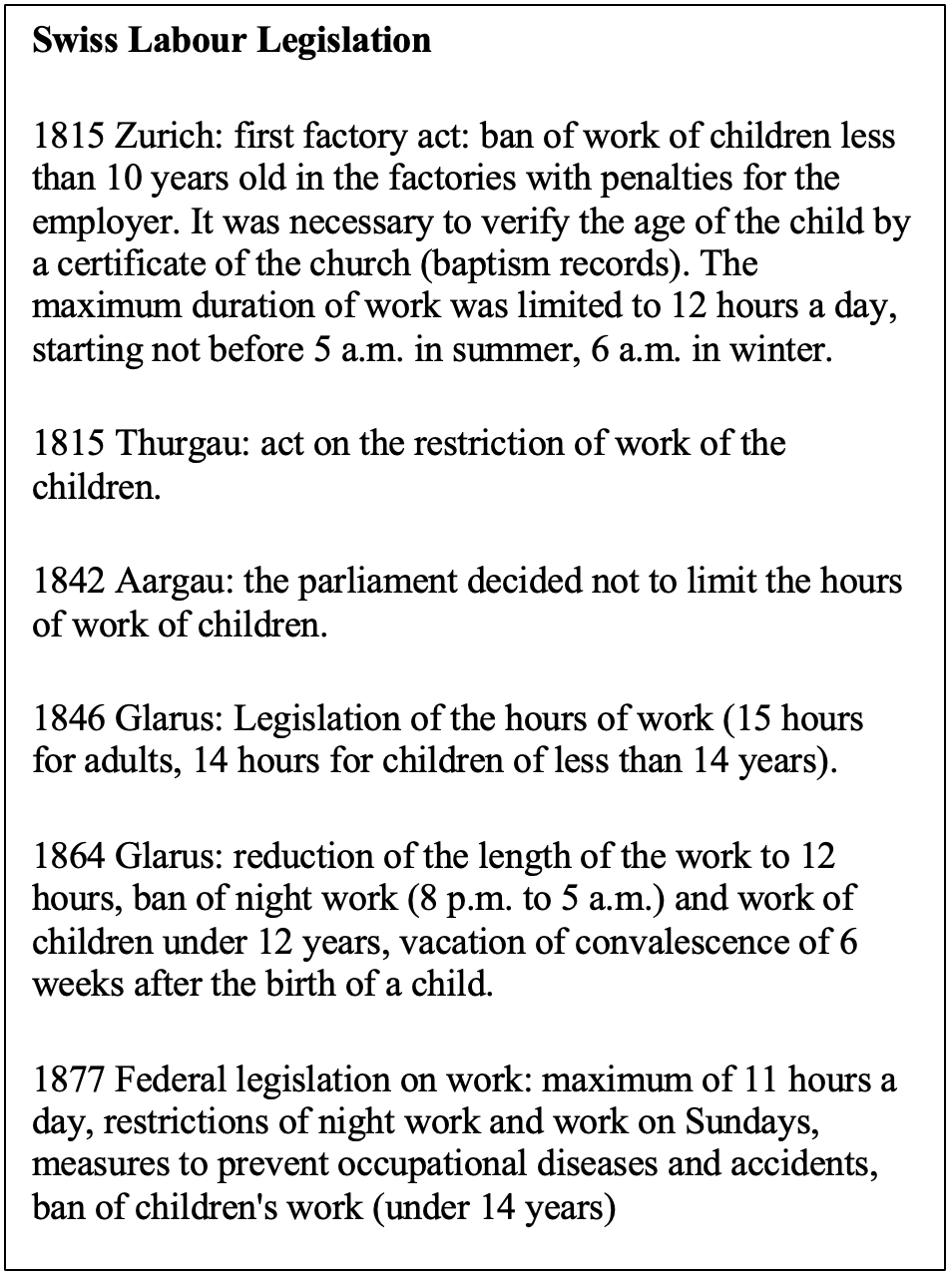

The absence of raw materials meant that Swiss industry did not concentrate in coal basins. There were no big industrial cities as Swiss industries tended to disperse along rivers supplying waterpower (ribbon development). Low wages and a less protected workforce helped Swiss manufacture to continue to compete effectively with the technologically advanced industry of Britain. For a long time, Swiss workers remained much less paid than in England and laws to protect workers were slower to be enacted. (See table opposite) But the living conditions for workers were relatively better, and prices and rents in Switzerland were still much lower than in England.

Poor wages and child labour were two of the common features of the Swiss industrial revolution. It wasn’t until 1877 that federal laws were implemented to outlaw the employment of children (under 14 years of age.) As in Britain, employers were under no obligation to provide healthy housing or safe working conditions. On average, a factory worker had a life expectancy of 35 years, while wealthier citizens could live up to 55 years.

The development of the railways in Switzerland was relatively late. In the 1840s, individual cantons still imposed tariffs and tolls on people and goods that crossed their frontiers. The new federal constitution of 1848 enabled the planning and financing of railways and soon after there was rapid expansion with more than 1000km of line built in a 10-year period. By the time the federal government took over (nationalised) the railways in 1898, Switzerland had one of the densest railway networks in the world.

Socio-economic consequences

The absence of raw materials meant that Swiss industry did not concentrate in coal basins. There were no big industrial cities as Swiss industries tended to disperse along rivers supplying waterpower (ribbon development). Low wages and a less protected workforce helped Swiss manufacture to continue to compete effectively with the technologically advanced industry of Britain. For a long time, Swiss workers remained much less paid than in England and laws to protect workers were slower to be enacted. (See table opposite) But the living conditions for workers were relatively better, and prices and rents in Switzerland were still much lower than in England.

Poor wages and child labour were two of the common features of the Swiss industrial revolution. It wasn’t until 1877 that federal laws were implemented to outlaw the employment of children (under 14 years of age.) As in Britain, employers were under no obligation to provide healthy housing or safe working conditions. On average, a factory worker had a life expectancy of 35 years, while wealthier citizens could live up to 55 years.

|

The response of the working class

The development of trade unions and political parties was a gradual process and as in Britain it was opposed by employers who feared a loss of their competitivity. Also, as in Britain, the first responses of the working classes to the industrial revolution could be violent and targeted the machinery that threatened their jobs. The most famous incident took place in Uster, near Zurich in 1832. As in the north of industrial England, qualified handloom weavers saw their newly installed machinery forcing down the level of their wages. The coordinated attack on the Corrodi & Pfister spinning mill resulted in the destruction of the factory, 75 arrests and sentences of up to 24 years in prison with hard labour for the organisers. Although the first trade unions appeared as early in 1838, it was not until the 1870s with the foundation of l'Union syndicale suisse (USS) that real improvements in the conditions of work were achieved. The 1877 Factory Act restricted the length of the working day throughout Switzerland and safety measures were compulsorily introduced in the most dangerous industries. Workers wages increased four-fold in the second half of the 19th century, although health insurance to cover accidents at work was not introduced until 1912 and even then, it was not compulsory. Perhaps the key development in the history of the Swiss working class was the foundation of the Social Democratic Party on 21 October 1888. The SP was a socialist party committed to winning political power as a means of improving the lives of workers. But as in Britain, it wasn’t until after the first world war that the SP became a serious political force. |

1859 - The Battle of Solferino and Henry Dunant

The battle of Solferino was one of series of wars that helped to create the Italian state in the 1850s. The battle of Solferino marks a clear turning point in the history of war between what military historians call first and second generation warfare. On the one hand, Solferino was the last battle in which the armies were led into battle by their respective monarchs: Napoleon III of France (Nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of France from 1852 to 1870) and Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont (soon to be Italy) versus the young Austrian Franz Joseph who would still be Austrian emperor at the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914. The tactics used by both sides were the same as those used in the Napoleonic Wars, but the weapons used were mixture of the old and the new. Muzzle loaded muskets still dominated, but the new breach loaded rifles were also now in use. In general, France had the technological advantage. The French rifled cannon 'Napoleon' had an accurate range of over 3km and was far superior to the Austrian smooth bore cannon which had a 2km range.

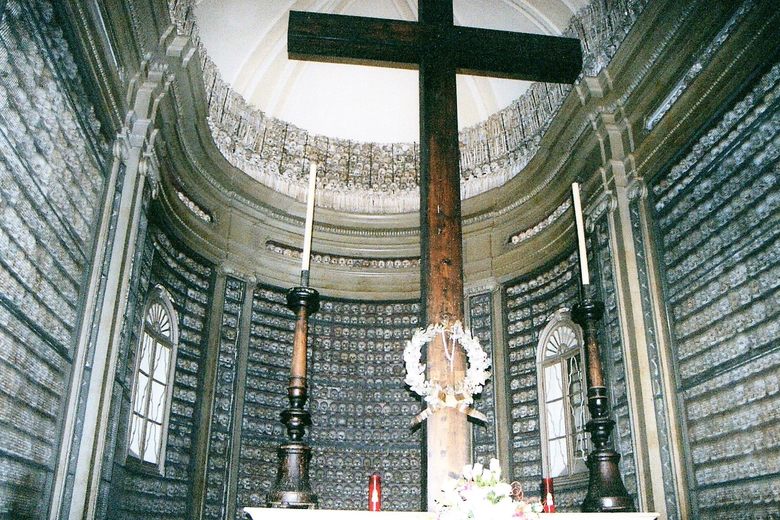

Even the memorials of Solferino mark a turning point between first and second generational war. The Ossuary at San Pietro, (below left) contains the bones of 7000 ordinary soldiers. The tower of San Martino della Battaglia is a memorial to Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of Italy.

Perhaps the most 'modern' second generational feature of the battle of Solferino was the size of the armies. With nearly 300,000 soldiers, this was the largest battle since Leipzig in 1813. This was made possible by the Industrial Revolution (Matu 4). A French army of 120,000 was transported and supplied by railway in less than two weeks, something that previously would have taken at least two months. 70,000 troops we also delivered be steamboat. This gave the French significant advantage over the Austrians who had marched on foot at 4km a day. But larger armies and more potent weapons also equalled greater numbers of casualties. It was, of course, the horror of Solferino that led a Swiss businessman to establish the Red Cross and to help establish the Geneva Convention to establish rules for the conduct of modern warfare.

The International Red Cross and the Geneva Convention

|

|

Henry Dunant was a Swiss businessman who 1859 by chance happened to arrive in Solferino a day after the biggest battle for over 50 years. He wrote a book about the horrors of his experience Un Souvenir de Solferino. About 40,000 soldiers on both sides died or were left wounded on the field. Up until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organised army nursing systems to treat casualties on the battlefield. Dunant set about putting such a system in place. On 9 February 1863 in Geneva, Henry Dunant founded what became the International Red Cross Committee (Henri Dufour - Matu 5 - was also one of the first five members). On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field".

|

|

The Geneva Convention

Representatives of 12 states signed the convention that provided for:

Due to the rapidly developing nature of war and military technology, the original articles had to be revised and expanded, largely at the Second Geneva Conference in 1906 and Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 which extended the articles to maritime warfare. Henry Dunant received the first Noble Peace Prize in 1901. |

World Wars and 20th Century Neutrality

The Matu history syllabus requires us to pay special attention to the question on Swiss neutrality. We are expected to 'trace Switzerland's path from one world war to the next and to situate the debate on neutrality in the light of political positions and economic commitments. To understand the transition from social confrontation (general strike) to social peace (labour peace). '

For some, neutrality is the defining characteristic of Switzerland. As we studied in the history course, Switzerland has been officially neutral since the Congress of Vienna in 1815. As a result, Switzerland has been the host of many international conferences to settle peace and has become the home of many international organisations – EFTA, Council of Europe, Red Cross (Henry Dunant) IMP, WTO, Fifa, Uefa, IOC etc.

For some, neutrality is the defining characteristic of Switzerland. As we studied in the history course, Switzerland has been officially neutral since the Congress of Vienna in 1815. As a result, Switzerland has been the host of many international conferences to settle peace and has become the home of many international organisations – EFTA, Council of Europe, Red Cross (Henry Dunant) IMP, WTO, Fifa, Uefa, IOC etc.

|

|

|

During World War I and World War II, Switzerland maintained armed neutrality. As we have seen previously, Switzerland's independence also suited the other nations as a centre for for diplomacy, banking and commerce, as well as being a safe haven for refugees.

World War I

World War I

|

With two of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and two of the Entente Powers (France and Italy) all sharing borders and populations with Switzerland, neutrality proved difficult but essential. Just as the United States feared being divided by a war that set its European national groups against each other, so to Switzerland where French and German linguistic groups supported their respective sides the problem of national unity was very real.

German war planner von Schlieffen had considered the possibility of an outflanking attack on France via Switzerland but attractive flat Belgian terrain and inferior Belgian defences compared favourably to the challenge of Swiss mountains and a regular Swiss army of 218,000 men which had been recently modernised. Switzerland mobilised its army on August 7, 1914 largely on the Jura border with France. From May 1915 the southern border with Italy was similarly guarded. |

The economic warfare waged by the belligerents had a major impact on Switzerland, which was completely surrounded by warring countries for the first time since 1815. This led to a significant increase in inflation: the rise in the cost of basic goods (food, clothing and fuel in particular) was much greater than the increase in wages, causing a loss of almost 30% of workers' purchasing power. Moreover, soldiers, who served an average of 500 days during the war, only received their daily pay and no salary allowances, thus increasing the impoverishment of the population. In autumn 1917 the Swiss government introduced a food rationing plan.

|

Because Switzerland was centrally located, neutral, and generally undamaged, the Swiss banking industry flourished. For the same reasons, Switzerland became a haven for foreign refugees and revolutionaries, of which Lenin and the Bolsheviks would become the most significant. During the war Switzerland also accepted 68,000 British, French and German wounded prisoners of war for recovery in mountain resorts. The transfer was agreed between the warring nations and organised by the Red Cross. Many of these soldiers died in Switzerland which explains the presence of military war graves in Switzerland. When the Germans and the Allies signed the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919, they confirmed the neutrality of Switzerland. Following the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, several regions bordering the new Austria sought to integrate with their neighbours. In a plebiscite held on 11 May 1919, 82% of the inhabitants of Vorarlberg approved a unilateral declaration of independence and a request to join Switzerland. However, the victorious Allies disregarded the popular vote and awarded Vorarlberg to Austria in the Treaty of St. Germain.

|

|

|

The League of Nations was established in Geneva and in 1920 a small majority of Swiss voted in favour of joining. The League of Nations accepted the 'differential neutrality' of Switzerland, which meant that the country was obliged to participate in economic but not military sanctions. Despite this, Switzerland refused to impose economic sanctions on Mussolini's Italy during the Abyssinian crisis (and even refused to allow Abyssinian emperor Haile Selassie to live in his house in Vevey!) Somewhat embarrasingly in 1937 the University of Lausanne awarded Mussolini an honorary doctorate. With the collapse of the League of Nations, Switzerland once again became 'absolutely' neutral. |

|

Switzerland in the interwar years.

The economic difficulties of the war years, the increasing prominence of the Socialist Party (SP) and rise in industrial unrest and demonstrations created a fear among conservatives that Switzerland might fall to the same forces that had provoked revolutions throughout central Europe. In Olten, in February 1918 leaders of the socialists, the country's trade unions, and the socialist newspapers created the Olten Action Committee (OAK) designed to better organise the workers demands. After the collapse of Germany and the revolutions in 1918, the Federal Government took preemptive action against a potential left-wing rising and ordered the army to occupy Zurich. In response the OAK called for a General Strike, which although ultimately defeated did lead to significant improvements in wages and the introduction of the 48 hour working week. |

(Above - Soldiers guarding the Federal Palace in Berne)

|

The early 1920s, as in much of Europe, was marked by an economic crisis and significant industrial unrest. The textiles and watchmaking industries were particularly impacted. In contrast, the traditionally important banking sector benefitted from Swiss neutrality in the First World War and in the interwar years Swiss financial services became the most important in the world. This was further encouraged by the banking law of 1934 which formalised the tradition of banking secrecy which enabled the world's super-rich to hide their assets.

Politically the interwar years saw Switzerland generally the avoid the polarised extremism that characterised the period in much of Europe. A popular initiative in 1918 established a system of proportional representation. The main beneficiaries were the smaller parties such as the Socialists and the newly formed conservative and Protestant Party of Farmers, Traders and Independents (BGB). In 1921 the Swiss socialists became an officially reformist democratic party, rejecting the revolutionary Marxist tradition. The rise of fascism in Europe did encourage the creation of similar extreme rightwing 'frontist' parties in Switzerland but the federal, regional identity of Switzerland inhibited the growth of the movement.

Politically the interwar years saw Switzerland generally the avoid the polarised extremism that characterised the period in much of Europe. A popular initiative in 1918 established a system of proportional representation. The main beneficiaries were the smaller parties such as the Socialists and the newly formed conservative and Protestant Party of Farmers, Traders and Independents (BGB). In 1921 the Swiss socialists became an officially reformist democratic party, rejecting the revolutionary Marxist tradition. The rise of fascism in Europe did encourage the creation of similar extreme rightwing 'frontist' parties in Switzerland but the federal, regional identity of Switzerland inhibited the growth of the movement.

|

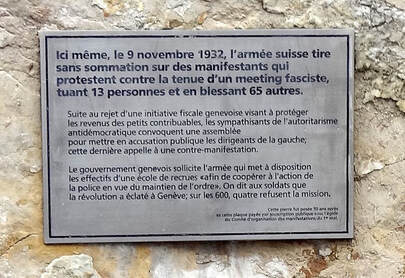

Geneva fusillade of 9 November 1932

On 9 November 1932, the Swiss Army fired live rounds into a crowd of anti-fascist protesters in Plainpalais in Geneva, killing 13 and wounding 65. The English newspaper, the Guardian wrote at the time: 'it is not doubtful that in any English town the police would have sufficed to settle such a insignificant affair (...) nothing in these events constituted a riot (...) In my long experience, I have never have known of a case in which the crowd was fired upon with such flimsy reasons. Or more to the point, without any reason whatsoever.' This was the last time troops were sent to act against public unrest in Switzerland. For more see this illustrated article at notreHistoire or listen to this RTS special broadcast. |

|

|

In the 1930s, with the support of all major political parties and in response to the aggressive foreign policies of her fascist neighbours, Switzerland significantly increased its federal budget for the military. This was made possible by the movement to the right by the Swiss socialists who broke with their pacifist traditions and supported the need for national defence. This political unity also encouraged an agreement between trade unions and management to establish in July 1937 the Paix du travail, 'labour peace agreement', which initiated a tradition of industrial conciliation and negotiation which made strikes a rarity in Switzerland. This began first with watch making and gradually spread to other industries. |

|

World War II

Maintaining Swiss neutrality in WWII was altogether more challenging than in WWI and had some consequences that make the historical narrative considerably more contentious. The title of the film opposite sums up the debate: how neutral was Switzerland during WWI? When war broke out on 1 September 1939, Switzerland mobilised 430,000 combat troops and 200,000 reserves. The Federal Assembly appointed Henri Guisan, from Vaud, as General of the Swiss Armed Forces. He was to play an important role in how Switzerland conducted itself during the war. |

|

(Above - 25th July 1940, Henri Guisan addresses the most senior officers of the Swiss army at the historic site of Grütli meadow, where the founding three Swiss cantons met in 1281. Here he announced the Swiss war strategy - the Reduit - which rejected any prospect of Swiss accommodation with Nazi Germany '...the meeting had an electrifying effect on the army, whose morale greatly improved' Church and Head, A concise history of Switzerland p.215. The meeting itself has also since become legend.)

With the fall of France in 1940 and completely surrounded by the Axis fascist regimes, some in Switzerland called for an appeasing accommodation with Hitler. The extremist Swiss fascist 'fronts' reappeared and Confederation President Marcel Pilet-Golaz of Cossonay, seemed to be considering the possibility of the creation of an authoritarian government, he was not alone. But the military policy of Henri Guisan - the national redoubt 'Reduit' - which envisaged almost a scorched-earth military retreat into Alps probably did much to deter Hitler and to galvanise Swiss resistance. Eventually, 360,000 soldiers were stationed in the Reduit at a cost of 900m francs.

Unlike in WWI, steps were taken by government to improve standards of social welfare. This time the conscripted soldiers were compensated for their time. The funding of these payments through the deduction of a given percentage of the person's salary would later serve as a model for the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (AHV/AVS). In addition, rents were frozen and tenants protected, improvements were made to family allowances and unemployment insurance. The basis of the modern Swiss social welfare was put in place.

|

Jews, gold and the Bergier Report

After WWII, the Swiss were generally proud that they had been able to maintain their armed neutrality in the face of overwhelming odds. In the 1990s this positive narrative came under sustained attack internationally. In 1995 the Jewish World Congress made three key criticisms of Switzerland in WWII. Firstly, Switzerland willing received and hid gold that had been stolen as the Nazis conquered Europe. Secondly, Swiss banks continued to hold the accounts of European Jews who had been killed in the Holocaust - dormant accounts - without having made any effort to return the money to surviving relatives. |

|

|

Finally, Nazi Germany was Switzerland's most important trading partner during WWII, providing the Nazis with essential war supplies and weapons made by state-owned manufacturers which was contrary to the 1907 Hague Convention.

In December 1996, the Swiss Federal Government setup a Committee to investigate Switzerland's role in World War II. The chair was historian Jean-François Bergier from the University of Geneva. When asked why he accepted such an investigative and editing role, Bergier replied, "Above all there's the issue of Switzerland's historical responsibility. You have to be responsible for your past. On that condition you can face the future clearly and calmly." It was a critical and controversial report that confirmed many of the international criticisms that had been made over the previous decade.. |

|

In reality, Swiss neutrality was already compromised before the outbreak of the war. In 1938 for example, Switzerland proposed that Germany stamp the passports of Jews with a letter 'J' so as to make it easier to identify them and prevent cross border travel. When the 'Final Solution' was initiated in Nazi Germany, Switzerland announced it was closing it borders. 'Refugees fleeing on racial grounds, such as Jews, are not entitled to political asylum.' In fact, Swiss frontiers were only re-opened to refugees from July 1944.

|

|

|

Since World War II

The syllabus does not appear to require that we go beyond World War II but it would be a shame not to bring things up to the present day. In brief, since WWII (and as a result of globalisation) Switzerland has become increasingly tied into international organisations which have inevitably weakened both her neutrality and national sovereignty. For example, in 2002 Switzerland joined the UN. In addition, joining organisations like EFTA and signing a series of bilateral agreements with the EU (between 1999-2004) meant that Switzerland was forced to abide by international treaties and laws that limit her independence. For example, the Schengen agreement which enable the free movement of people across EU states – so essential to the Swiss economy – is an extension of the right to free movement which allows European citizens like me the right to live and work in Switzerland. For example, in 2014 the federal popular initiative "against mass immigration" from the Swiss People's Party and was accepted by a majority of the electorate 50.3%. Theoretically if this law had been enabled, all Switzerland’s agreements with the EU would have been cancelled. In the end the initiative was effectively ignored, and a compromise settlement was reached with the EU. This outcome was decried as a failure to properly implement the referendum by the Swiss SVP party (which had promoted the referendum) as it fails to put any curbs on immigration. A second attempt by the SVP in 2020 to introduce immigration restrictions was rejected by 61.7%.

More recently (May 2021) the failure after seven years of negotiation to reach a trade treaty with the EU is likely once again to put pressure on Switzerland's ability to maintain its sovereignty and independence. The negotiation collapsed due to Switzerland’s rejection of the jurisdiction of the European court of justice, and of a free movement directive that would offer permanent residence to EU citizens, with access to social security granted to non-employed residents such as job-seekers and students. It is likely that Swiss-EU relations will become increasingly strained over the coming months and years.

Finally, two recent events in early 2022 have pontentially significant implications for the traditions of Swiss banking and political neutrality. In February 2022 an investigation by international journalists revealed the extent to which Swiss banking continues to fund international corruption. Then in February, the Russian invasion of Ukraine saw the Swiss break with its traditional neutrality by supporting the European Union's imposition of sanctions against Russia.

Extra

Swiss history as illustrated by political posters.

The syllabus does not appear to require that we go beyond World War II but it would be a shame not to bring things up to the present day. In brief, since WWII (and as a result of globalisation) Switzerland has become increasingly tied into international organisations which have inevitably weakened both her neutrality and national sovereignty. For example, in 2002 Switzerland joined the UN. In addition, joining organisations like EFTA and signing a series of bilateral agreements with the EU (between 1999-2004) meant that Switzerland was forced to abide by international treaties and laws that limit her independence. For example, the Schengen agreement which enable the free movement of people across EU states – so essential to the Swiss economy – is an extension of the right to free movement which allows European citizens like me the right to live and work in Switzerland. For example, in 2014 the federal popular initiative "against mass immigration" from the Swiss People's Party and was accepted by a majority of the electorate 50.3%. Theoretically if this law had been enabled, all Switzerland’s agreements with the EU would have been cancelled. In the end the initiative was effectively ignored, and a compromise settlement was reached with the EU. This outcome was decried as a failure to properly implement the referendum by the Swiss SVP party (which had promoted the referendum) as it fails to put any curbs on immigration. A second attempt by the SVP in 2020 to introduce immigration restrictions was rejected by 61.7%.

More recently (May 2021) the failure after seven years of negotiation to reach a trade treaty with the EU is likely once again to put pressure on Switzerland's ability to maintain its sovereignty and independence. The negotiation collapsed due to Switzerland’s rejection of the jurisdiction of the European court of justice, and of a free movement directive that would offer permanent residence to EU citizens, with access to social security granted to non-employed residents such as job-seekers and students. It is likely that Swiss-EU relations will become increasingly strained over the coming months and years.

Finally, two recent events in early 2022 have pontentially significant implications for the traditions of Swiss banking and political neutrality. In February 2022 an investigation by international journalists revealed the extent to which Swiss banking continues to fund international corruption. Then in February, the Russian invasion of Ukraine saw the Swiss break with its traditional neutrality by supporting the European Union's imposition of sanctions against Russia.

Extra

Swiss history as illustrated by political posters.