Lesson 5 - The storming of the Bastille

What really happened at the Bastille?

The fall of the Bastille was the most famous event of the French Revolution. It was a symbol of the victory of ordinary people over the power of their rulers. It is the day the French have chosen as their national day. Their victory was recorded in many thousands of drawings and paintings. The Bastille doesn't exist today, it was torn down soon after the revolution. Consider the six images in the presentation below.

The fall of the Bastille was the most famous event of the French Revolution. It was a symbol of the victory of ordinary people over the power of their rulers. It is the day the French have chosen as their national day. Their victory was recorded in many thousands of drawings and paintings. The Bastille doesn't exist today, it was torn down soon after the revolution. Consider the six images in the presentation below.

|

|

Discussion in pairs

How would you describe the Bastille as a building? How are the crowd of revolutionaries depicted in the images? How are the prison cells depicted? |

The events at the Bastille were celebrated all over Europe. Image 6 above 'The Triumph of Liberty' was produced by the English cartoonist James Gillray who we have seen before and who we will see again. The English Romantic poet William Wordsworth wrote of the revolution “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven.” Perhaps the most famous English perspective on the revolution was provided by Charles Dickens in his novel 'A Tale of Two Cities'. (We will also come across Dickens again later in Matu 4)

In the following famous scene, Dickens has the character 'Defarge of the wine shop' and his wife attacking the Bastille. Read the text carefully and then in pairs consider the questions which follow.

Cannon, muskets, fire and smoke; but, still the deep ditch, the single drawbridge, the massive stone walls, and the eight great towers. Slight displacements of the raging sea, made by the falling wounded. Flashing weapons, blazing torches, smoking waggon-loads of wet straw, hard work at neighbouring barricades in all directions, shrieks, volleys, execrations, bravery without stint, boom, smash and rattle and the furious sounding of the living sea; but, still the deep ditch, and the single drawbridge, and the massive stone walls, and the eight great towers, and still Defarge of the wineshop at his gun, grown doubly hot by the service of Four fierce hours.

A white flag from within the fortress, and a parley - this dimly perceptible through the raging storm, nothing audible in it - suddenly the sea rose immeasurably wider and higher, and swept Defarge of the wine-shop over the lowered drawbridge, past the massive stone outer walls, in among the eight great towers surrendered!

So resistless was the force of the ocean bearing him on, that even to draw his breath or turn his head was as impracticable as if he had been struggling in the surf at the South Sea, until he was landed in the outer court-yard of the Bastille. There, against an angle of a wall, he made a struggle to look about him. Madame Defarge, still heading some of her women, was visible in the inner distance, and her knife was in her hand. Everywhere was tumult, exultation, deafening and maniacal bewilderment, astounding noise...

‘The Prisoners!’

‘The Records!’

‘The secret cells!’

‘The instruments of torture!’

‘The Prisoners!’

Of all these cries, ‘The Prisoners!’ was the cry most taken up by the sea that rushed in, as if there were an eternity of people, as well as of time and space.

|

Discussion in pairs

How does Dickens describe the Bastille? How does Dickens portray the crowd of revolutionaries? What is the goal of the revolutionaries? Now watch the film version of a Tale of Two Cities. How does it support what we have already seen in the pictures and in the words of Dickens. |

|

The historical record

Many of the artists who were inspired by the French Revolution were rather less concerned with the historical record than the drama of the event. They helped to create and perpetuate a series of myths about what happened at the Bastille. A myth is a traditional story, especially one concerning the early history of a people and supernatural explanations. You will have come across myths in 9e, when studying Greece and Rome. Myths may be based on real events but they are not supported by the historical record. Myths continue to be repeated because they are useful.

History is very different to myths. Historical accounts must be based on the evidence that the past has left behind. So let's look at some of the evidence.

History is very different to myths. Historical accounts must be based on the evidence that the past has left behind. So let's look at some of the evidence.

The crowd of revolutionaries

Much more recently, historians have used sources from the time to trace the professions of about 700-800 members of the crowd that stormed the Bastille. They have found out the following:

About five sixths were skilled craftsmen (such as joiners, locksmiths, cobblers, clockmakers), shopkeepers and other small tradesmen, clerks and journeymen. There were some labourers and wage-earning workers but nearly all were skilled workmen or ‘artisans’. About one sixth was made up of richer tradesmen - including some factory owners and merchants - soldiers, officers and a handful from the professions (such as lawyers, doctors and teachers).

How do these conclusions compare to the descriptions of the crowd you saw earlier?

Much more recently, historians have used sources from the time to trace the professions of about 700-800 members of the crowd that stormed the Bastille. They have found out the following:

About five sixths were skilled craftsmen (such as joiners, locksmiths, cobblers, clockmakers), shopkeepers and other small tradesmen, clerks and journeymen. There were some labourers and wage-earning workers but nearly all were skilled workmen or ‘artisans’. About one sixth was made up of richer tradesmen - including some factory owners and merchants - soldiers, officers and a handful from the professions (such as lawyers, doctors and teachers).

How do these conclusions compare to the descriptions of the crowd you saw earlier?

The prisoners

The French historian Jacques Godechot has studied the sources of 1789 and concluded the following

'The attackers were astonished to find so few captives. Many believed there were others, hidden in some secret cavern or dungeon . .. On 18 July the four gaolers were questioned separately. They confirmed that the Bastille contained, on 14 July, only seven prisoners: Solages, Whyte, Tavernier, Béchade, La Corrège, Pujade and Laroche. The latter four, common law prisoners accused of forgery, disappeared soon after and were never seen again. The Count of Solages had been imprisoned at the request of his family ... Whyte was an Englishman, afflicted by madness, and on 15 July he was imprisoned in Charenton. Tavernier was equally mad and he too was sent to Charenton.'

The French historian Jacques Godechot has studied the sources of 1789 and concluded the following

'The attackers were astonished to find so few captives. Many believed there were others, hidden in some secret cavern or dungeon . .. On 18 July the four gaolers were questioned separately. They confirmed that the Bastille contained, on 14 July, only seven prisoners: Solages, Whyte, Tavernier, Béchade, La Corrège, Pujade and Laroche. The latter four, common law prisoners accused of forgery, disappeared soon after and were never seen again. The Count of Solages had been imprisoned at the request of his family ... Whyte was an Englishman, afflicted by madness, and on 15 July he was imprisoned in Charenton. Tavernier was equally mad and he too was sent to Charenton.'

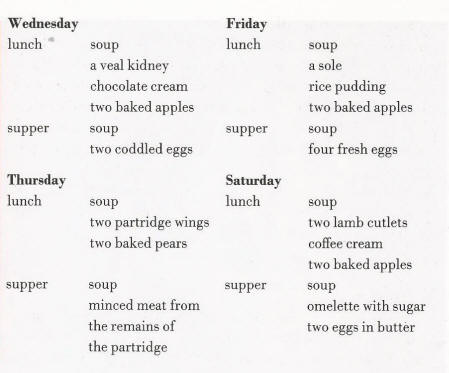

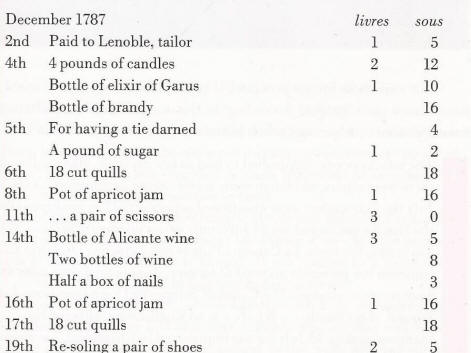

The following sources are extracts from the diary of the Marquis de Sade who was a prisoner inside the Bastille until a week before it was attacked. One is a list of some of the meals he ate there. The other is an account of his spending for the month of December 1787.

How does this evidence contrast with what you saw earlier?

How does this evidence contrast with what you saw earlier?

Activity

1. With reference to the artistic evidence provided above (paintings, novels and film), what do we mean by the 'myth' of the storming of the Bastille? Give examples of the myth to illustrate your answer.

2. With reference to other evidence provided, what was the reality of the storming of the Bastille?

3. Why do you think a myth of the storming of the Bastille developed and became so important?

1. With reference to the artistic evidence provided above (paintings, novels and film), what do we mean by the 'myth' of the storming of the Bastille? Give examples of the myth to illustrate your answer.

2. With reference to other evidence provided, what was the reality of the storming of the Bastille?

3. Why do you think a myth of the storming of the Bastille developed and became so important?