Lesson 5 - The social impact of the Industrial Revolution

The three social transformations of the Industrial Revolution.

The 19th Century German socialist Karl Marx argued that when we change the way we produce, we change the world. And because we are always looking to improve the way we produce, society is constantly changing. As he wrote in 1847:

‘Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.’

We can identify three interrelated social transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution:

The 19th Century German socialist Karl Marx argued that when we change the way we produce, we change the world. And because we are always looking to improve the way we produce, society is constantly changing. As he wrote in 1847:

‘Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.’

We can identify three interrelated social transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution:

- Urbanisation. The change in where people lived. People went from being village dwellers to being town dwellers. Towns grew rapidly with significant social consequences.

- New social classes. The change in who people were. The rise in the new entrepreneurial middle classes and urban working classes.

- New ways of working. The change in the mode and method of production resulting in new ways of earning a living.

1. Urbanisation

Why did the population grow so quickly?

Why did the population grow so quickly?

|

The birth rate rose, and the death rate fell. In other words, more babies were being born and fewer people died so early. As we have seen, improved more efficient farming methods resulted in better quality food being produced, and more of it. Canning food which helps preserve food (the examiners like this idea) and quicker transportation also better enabled the feeding of the towns.

Nutrition therefore improved for most people from the unborn child upwards. This helped reduce slightly the infant death rate and also improved the fertility of couples. Recently one historian has even claimed a role for tea drinking in improving life expectancy. |

Source 1 - The growth of towns from 1750 to 1851

|

Most importantly though, the growth of industry meant there were many new jobs and steady wages. This resulted in couples being able to get married and start having children at an earlier age. This meant simply that more children were being born.

What happened to the traditional ‘domestic system’ of industrial production?

What happened to the traditional ‘domestic system’ of industrial production?

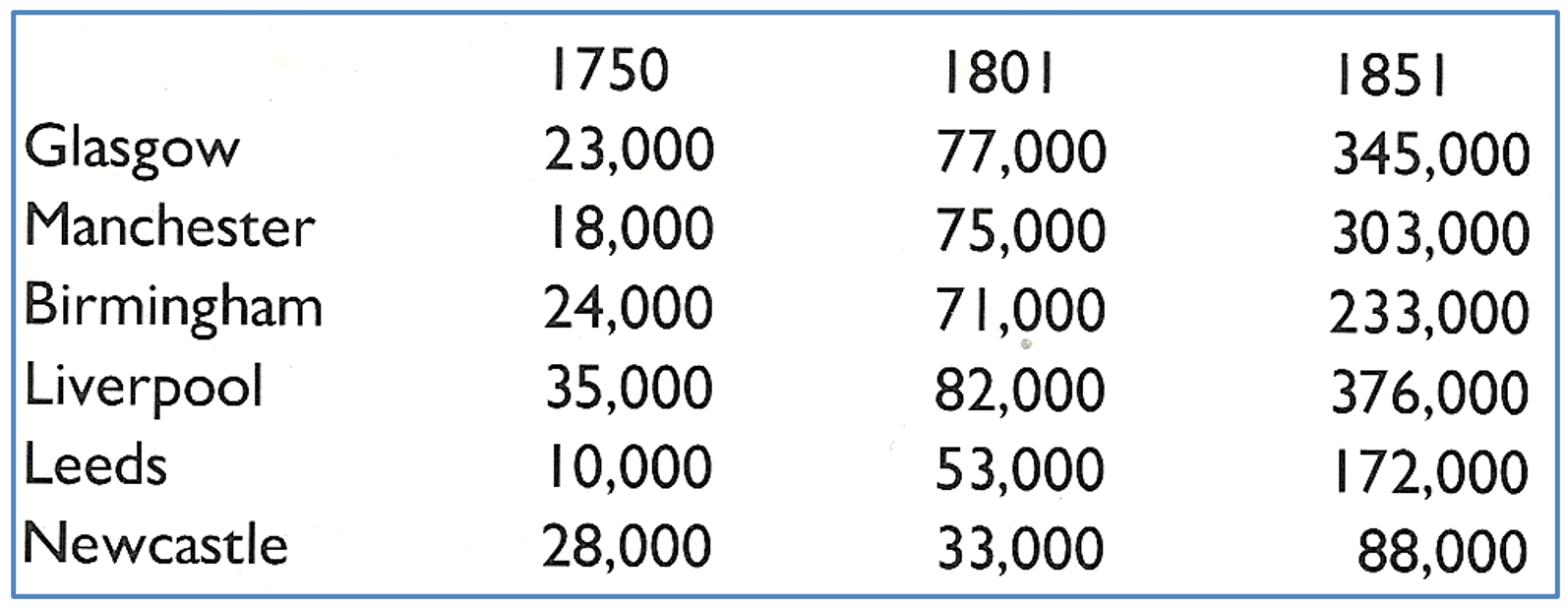

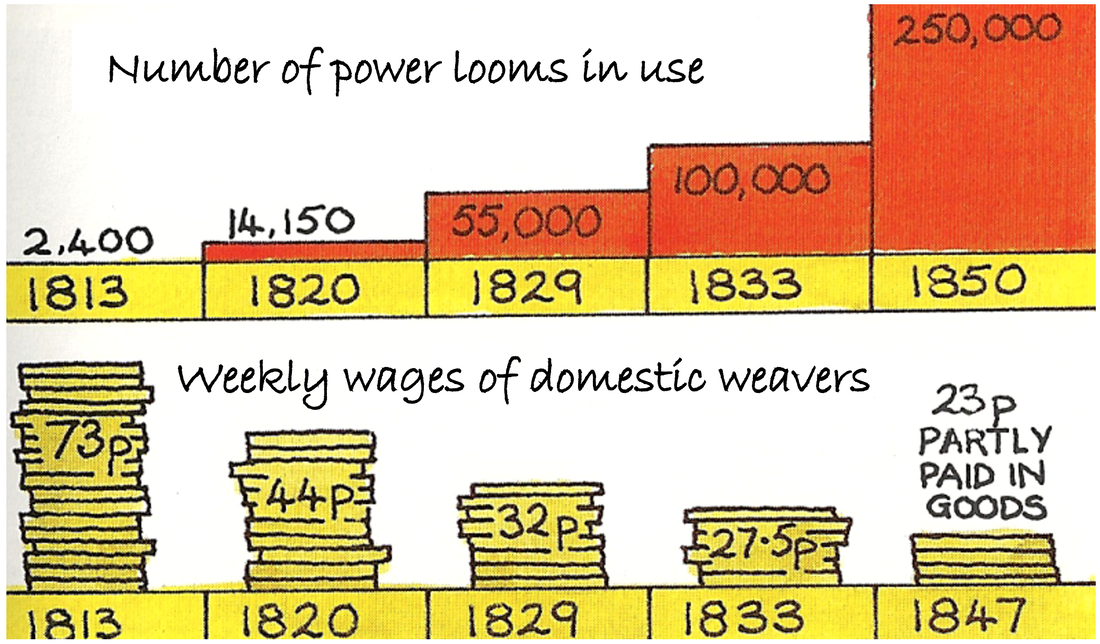

As the number of factories increased, the wages of domestic weavers went down. They simply couldn’t compete.

‘A very good handloom weaver, 25 or 30 years of age, will weave two pieces of [cloth] per week, each 24 yards long. In 1833, a power loom weaver, from 15 to 20 years of age, attending to four looms, can weave eighteen similar pieces in a week; some can weave twenty.’

|

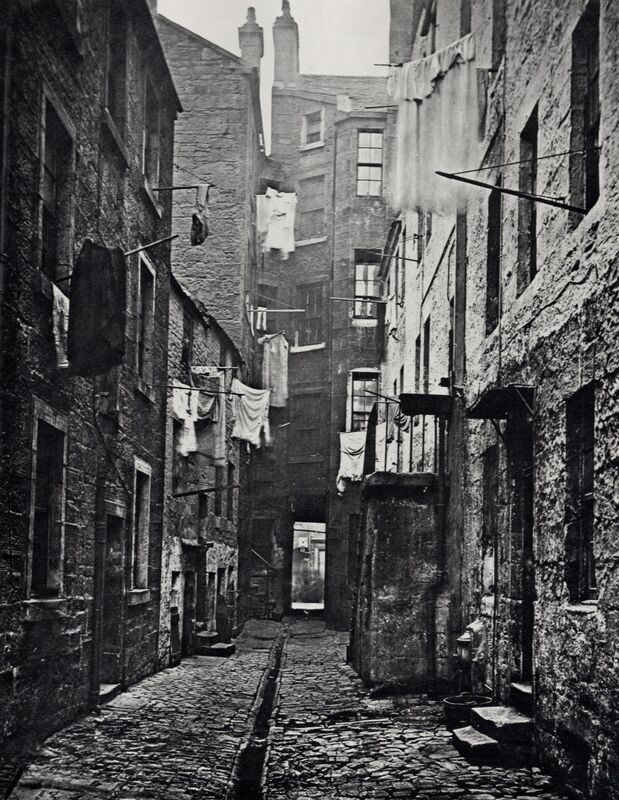

Gradually, the domestic workers, just like the poorer farmers we saw in a previous lesson, decided they had to leave the countryside to work in the new factory system around which the new towns grew up. This provided the new factory system with the workers it needed, but it also encouraged further innovation and ‘enclosure’ in the countryside, thereby forcing more poorer farmers to migrate to the towns. These farmers and domestic workers arrived in the towns, married earlier and the population grew further. Many more houses were needed, and most people living in towns had to suffer overcrowding in poorly built houses. Thousands of new houses were built in a very short time, without any rules on planning or quality |

|

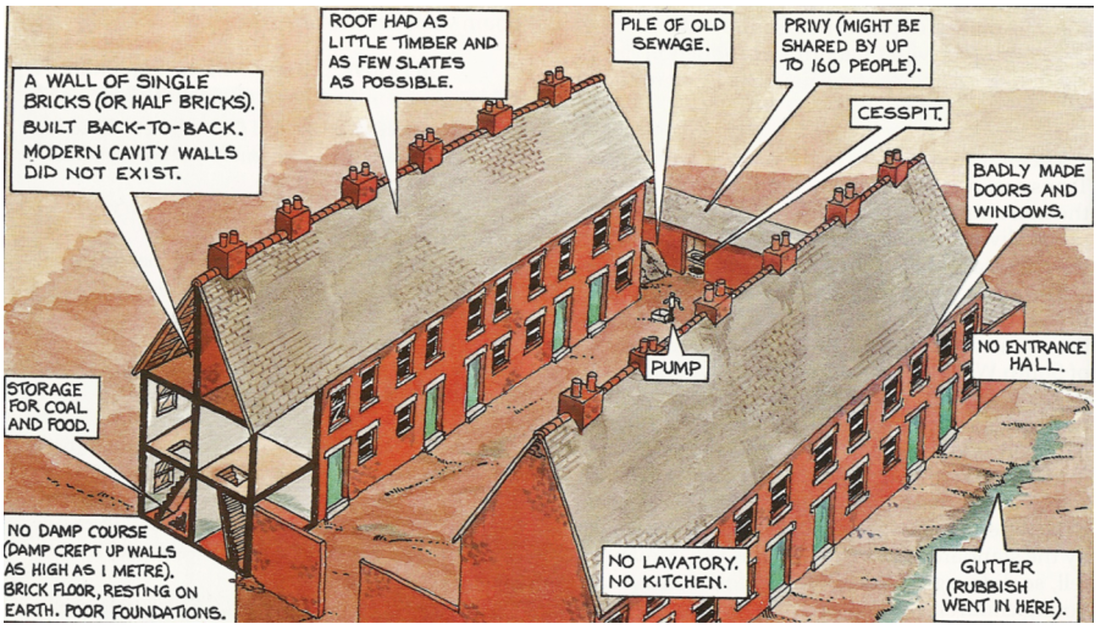

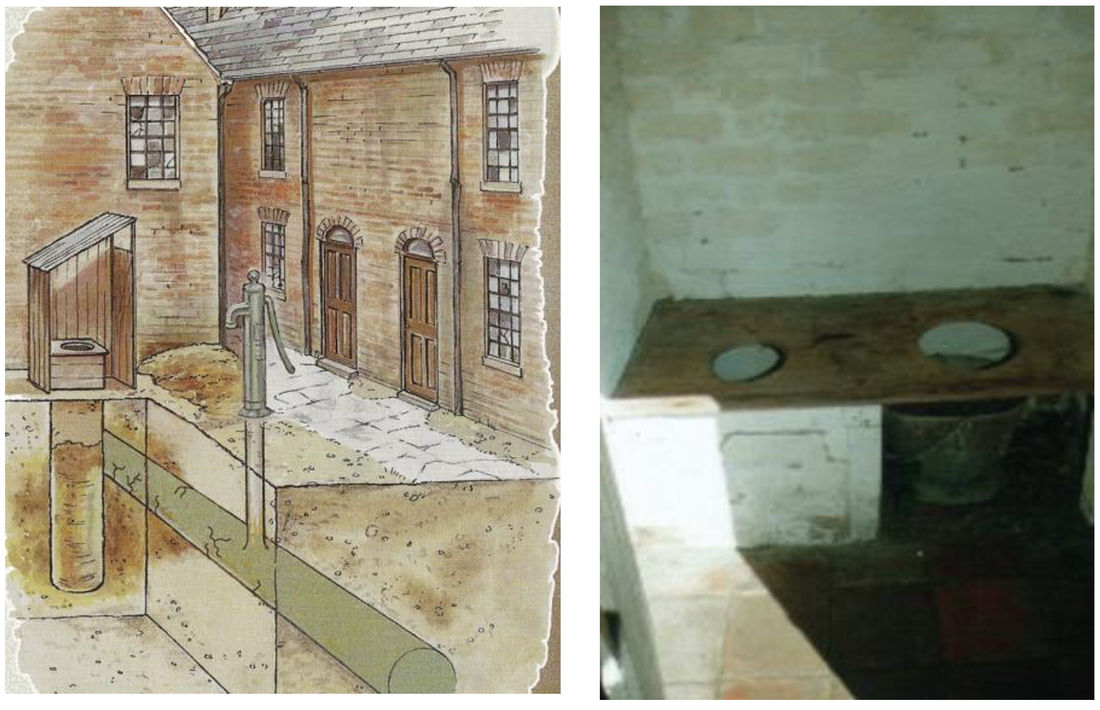

A contemporary writer explained why conditions were bad: ‘These towns have been built by small speculators with no interest for anything except immediate profit. A carpenter and a brick-layer club together to buy a patch of ground and cover it with what they call houses.’ Houses were crammed together, ‘back-to-back’. Many had no foundations, were damp and lacked ventilation. Very few had any form of sanitation. Sometimes there was a privy (primitive toilet) shared between several houses (below).

The shortage of housing often meant that one house accommodated several families, each having one room: ‘On the second floor lived a widow. In her room lived her grown-up son, two daughters, and two or three children of one of these daughters. Above on the third floor lived a market porter, his wife and four children.’ Charles Booth, 1889.

|

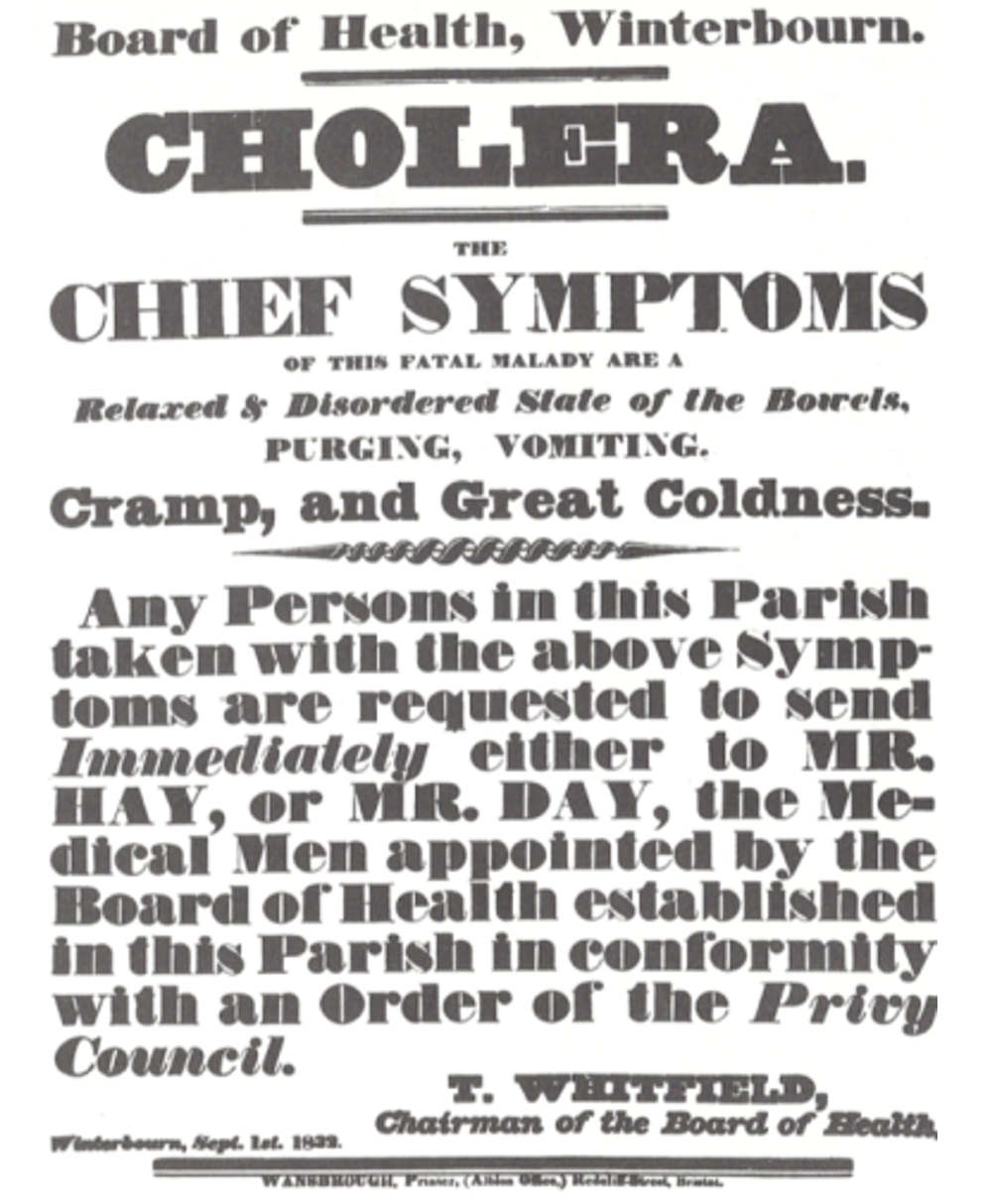

Most of these ‘slum’ dwellings contained little in the way of furniture. Many had just a table, a few chairs and a bed. Some did not even have that. A bed would be shared by several family members, and if some did shift work, the bed could be used night and day. Needless to say, the major effect of such poor, overcrowded and dirty housing was poor health. The awful living conditions were an ideal environment for diseases to spread. TB (tuberculosis), diphtheria, measles, cholera and influenza were just a few of the diseases which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Together with dangerous working conditions, long hours, poor diet and pollution, this resulted in an average life expectancy for the working class in Manchester of just 17 years.

|

Activities – Part 1 – Urbanisation

1. Explain carefully why the population grew so quickly during this period.

2. Explain both the causes and the consequences of the decline in the ‘domestic system’ in Britain.

3. Identify the main causes of poor living conditions in the early industrial phase and explain the main consequences of these conditions.

1. Explain carefully why the population grew so quickly during this period.

2. Explain both the causes and the consequences of the decline in the ‘domestic system’ in Britain.

3. Identify the main causes of poor living conditions in the early industrial phase and explain the main consequences of these conditions.

2. New social classes.

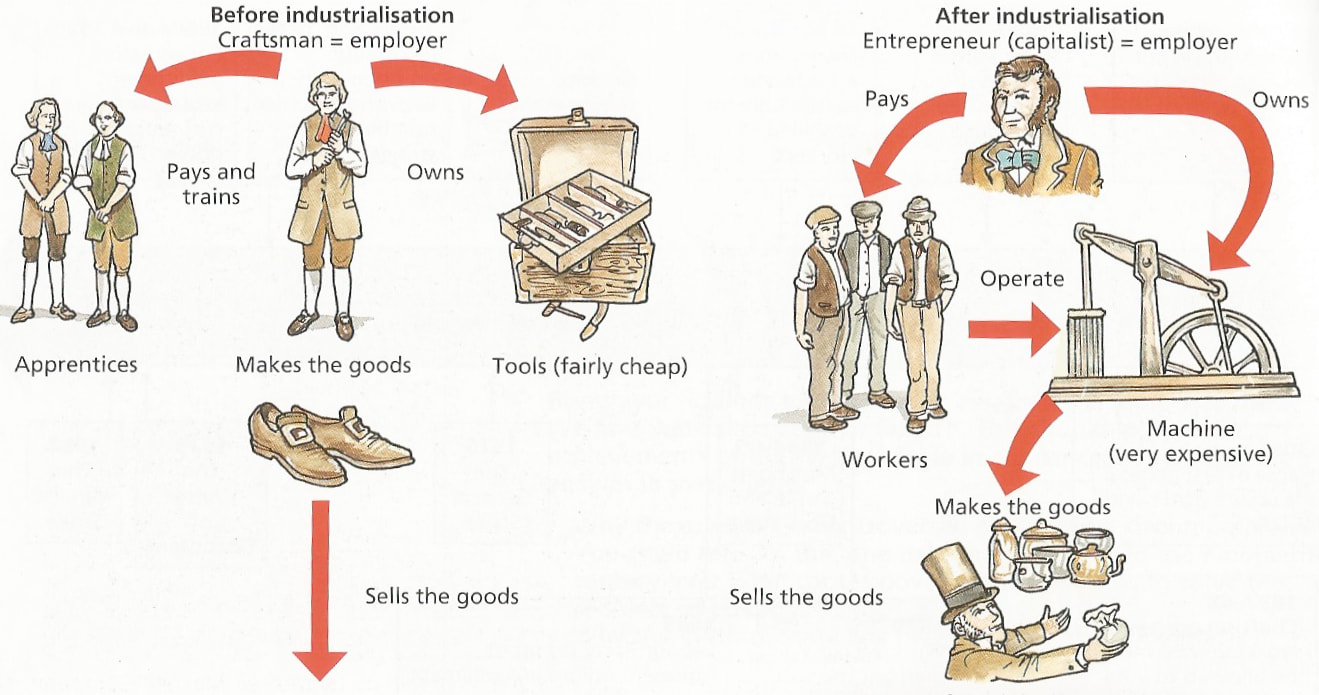

The second significant social consequence of the industrial revolution was the rise in new social classes. The creation of new types of work, new working contracts and new relations between employers and employees, transformed the very nature of what it meant to ‘work’. In particular, two new social classes appeared, a new entrepreneurial middle class that Marx called the bourgeoisie and the urban, industrial working class that Marx called the proletariat.

The second significant social consequence of the industrial revolution was the rise in new social classes. The creation of new types of work, new working contracts and new relations between employers and employees, transformed the very nature of what it meant to ‘work’. In particular, two new social classes appeared, a new entrepreneurial middle class that Marx called the bourgeoisie and the urban, industrial working class that Marx called the proletariat.

Diagram from Ben Walsh - British Social and Economic History 1997.

|

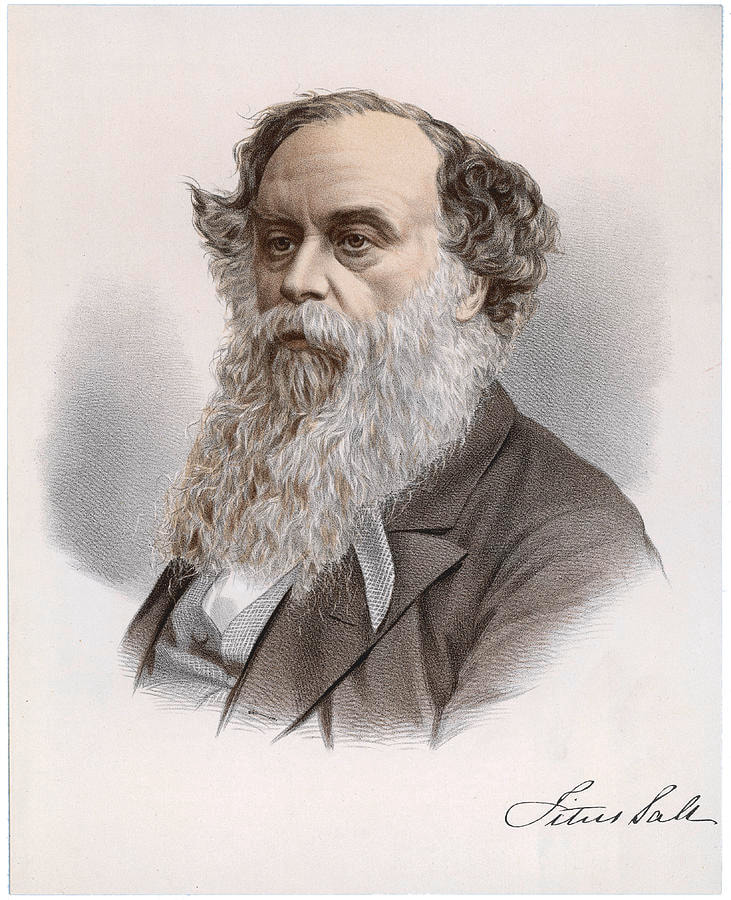

The new capitalist class, like Titus Salt (right) were sons of merchants and early industrialists. They made vast fortunes in the industrial revolution. They were owners of factories, mills, foundries and mines but also provided services to the expanded populations of the new towns. The new middle class had significant economic influence but little national political power because Parliament was still dominated by a ruling landowning aristocracy. Many of the new middle class campaigned for political reform and changes to favour the interest of the new industrial economy. They were often very influential in local politics and could have significant control over the lives of their workers. Compare and contrast these two very different video interpretations of the life of Titus Salt.

|

The new industrial working class were recent migrants from the countryside. They might be attracted by the freedom and excitement of the towns or driven from the countryside by declining wages and lost work opportunities. They were freed from feudal ties to sell their labour in the new factories, mines, foundries and civil engineering projects. They were unprotected, unorganised and easily exploited in badly paid, insecure and dangerous occupations. But they were also concentrated in greater numbers than ever before, better educated than the peasants of the countryside and like the capitalists, they were interested in more political power as a means of improving their lives. (Lesson 7)

|

For some, the new industries provided new opportunities for greater upward social mobility. In the countryside, social expectations, traditions and authority often determined how your life path would develop. Young men would inherit the trades or the small patch of land of their father. In the industrial revolution, your parent's occupation and social standing did not restrict the possibilities of self-improvement. Many successful industrialists were self made men from relatively humble backgrounds, who rose up through society through hard work, initiative and luck. But for most however, such social success remained a long way off as they worked long hours just getting by.

There was no group of workers more central to the Industrial Revolution and no group that more exemplified the insecurity and danger of industrial working class life than the navvies. The word ‘navvy’ came from the ‘navigators’ who dug and built the first navigation canals in the 18th century. Hundreds of thousands of them would be employed on the great engineering projects - notably the railways - throughout the 19th century. The nature of the work was typical of the new ways of working (below) but so also was the freedom and independence that characterised the new working class. Navvies were not feudal peasant farmers ancestrally tied to the land. The navvies freely entered into wage contracts and roamed the land following the work that needed doing. |

|

3. New ways of working.

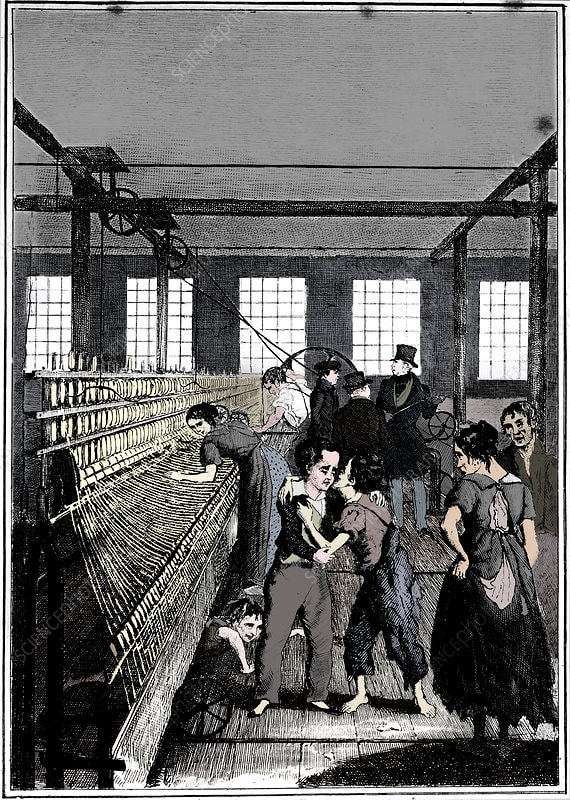

The third significant social consequence of the industrial revolution were the new working conditions. Today we expect our place of work to be safe and reasonably comfortable, but 200 years ago there were no laws governing health and safety. A factory owner’s main concern was how much profit he made, and he was free to do this as he wanted. If he paid his workers more and put in safety precautions, he had to spend more money and therefore made less profit. Very few factory owners were prepared to reduce profits by improving the working conditions of their labourers. Unlike the workers in traditional skilled industries who were protected and represented by guilds, the new industrial working class had no union representation and because they were unskilled could easily be replaced.

Many new machines were invented for mass producing in the factories. These cost a lot of money. That these machines were often dangerous for the operators was of little concern to the manufacturer. Usually he was more concerned if any accident delayed the production process. Accidents were commonplace and many people lost fingers, hands or limbs with no compensation. Some factories were so noisy that the workers went deaf. Factories were rarely heated in winter or ventilated in summer. Steam or gases often made the air unbearable. There was no protection against dangerous chemicals or gases and the owner was not liable for any injuries.

“The packer has to enter a chamber which has been filled with chlorine gas. Though the worst of it has been allowed to escape, the atmosphere is still charged with deadly fumes. The heat is tremendous. Gassing is such a common matter that the men would describe it as they would tell you what their Sunday dinner was like.” Reference to ‘bleach powder packers’ in a Home Office report of 1893.

“She was caught by her apron, which wrapped around the shaft. She was whirled round and repeatedly forced between the shaft and the carding engine. (Her right leg was found some distance away.)” A factory inspector reporting what happened to a young girl in a textile factory in the 1840s.

“She was caught by her apron, which wrapped around the shaft. She was whirled round and repeatedly forced between the shaft and the carding engine. (Her right leg was found some distance away.)” A factory inspector reporting what happened to a young girl in a textile factory in the 1840s.

|

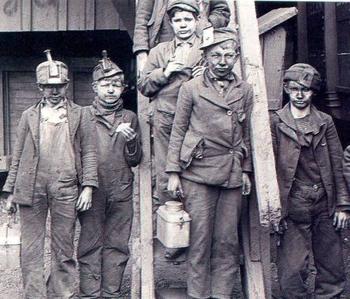

Perhaps the most shocking aspect of early industrial revolution was the use of child labour. Children had always worked in the domestic system and on the farms. The extra money they made was also welcomed by working class families. Many children, from as young as six years old, were employed because they could be paid very little and were small enough to crawl under the machines. Often, they would be beaten to keep them awake. |

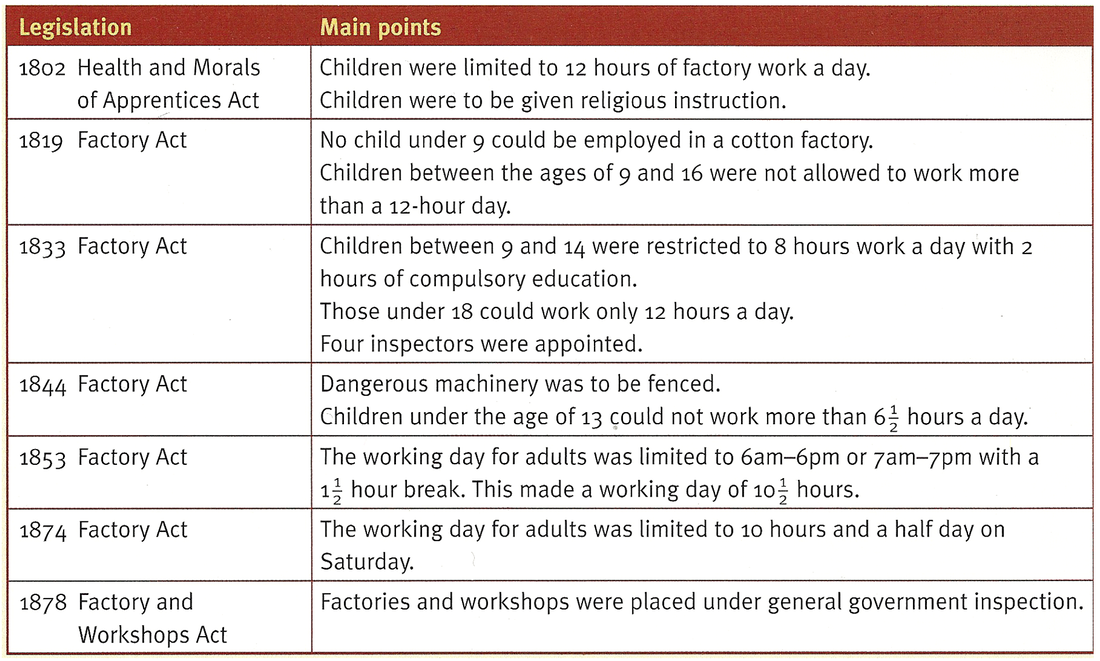

All workers were fined for being late or slowing down in their work and they could be sacked immediately with no explanation. Gradually, as a result of popular and political pressure (see future lesson on politics), laws were passed to regulate some of the worst excesses of the early industrial revolution in Britain. A strong humanitarian campaign had grown outside Parliament, championed by the Earl of Shaftesbury and Michael Sadler. The 'Ten-Hour Movement' aimed to reduce the working day for children under 16. A Royal Commission produced reports full of details of the appalling abuse and mistreatment of children in factories. This was popularised through the novel by Frances Trollope (see below).

In 1833 Parliament passed a new Factory Act. Previous Acts had been restricted to the cotton industry, but the 1833 Act also applied to the older woollen producing communities in and around Yorkshire which had been ignored in previous legislation. What made the 1833 Act so important was that it established a system to ensure that regulations were enforced. A small, four-man 'inspectorate of factories' was created, responsible to the Home Office, with powers to impose penalties for infringements. In its early days the inspectorate was far too small to enforce the Act in 4,000 mills, and so the Act was widely evaded. It did, however, create the beginnings of a much-needed system of government control.

In 1833 Parliament passed a new Factory Act. Previous Acts had been restricted to the cotton industry, but the 1833 Act also applied to the older woollen producing communities in and around Yorkshire which had been ignored in previous legislation. What made the 1833 Act so important was that it established a system to ensure that regulations were enforced. A small, four-man 'inspectorate of factories' was created, responsible to the Home Office, with powers to impose penalties for infringements. In its early days the inspectorate was far too small to enforce the Act in 4,000 mills, and so the Act was widely evaded. It did, however, create the beginnings of a much-needed system of government control.

Activities – Part 2 – New social classes and working conditions.

1. Briefly outline the main characteristics of the new capitalist class and new working class.

2. Both workers and capitalists, wanted to see changes in how the country was run. What changes do you think the workers wanted? What changes do you think the capitalists wanted? Do you think they could agree on any changes?

3. Using the table of legislation (laws) passed in 19th century England below, identify three different working conditions that would have been allowed in 1800. For example, workers were not protected from dangerous machinery because a law wasn’t passed to ‘fence dangerous machinery’ until the 1844 Factory Act.

1. Briefly outline the main characteristics of the new capitalist class and new working class.

2. Both workers and capitalists, wanted to see changes in how the country was run. What changes do you think the workers wanted? What changes do you think the capitalists wanted? Do you think they could agree on any changes?

3. Using the table of legislation (laws) passed in 19th century England below, identify three different working conditions that would have been allowed in 1800. For example, workers were not protected from dangerous machinery because a law wasn’t passed to ‘fence dangerous machinery’ until the 1844 Factory Act.

Extension and extras

|

Steven Johnson is an author I enjoy reading and someone who I will mention in the TOK lessons for Double Diploma students.

In this TedTalk from 2007 (right) Johnson looks at the cholera epidemic of 1854 and what that shows us about the problems London faced in being the first modern city.

|

|

The talk focusses on the work of Dr John Snow, the man who managed to persuade London's authorities - with the help of his famous map - that the source of the cholera epidemic was the infected water supply.

These three BBC schools dramatic documentaries provide you with a good overview of the issues of this lesson.

|

|

|

|