Lesson 6 - Italian Unification - 1848-70

The section which follows is based on an edited extract from History of Europe and the Middle East, IB Course Companion 2010.

The section which follows is based on an edited extract from History of Europe and the Middle East, IB Course Companion 2010.

|

|

You could do worse than to start with an overview from JG.

|

The story of Italian Unification is relatively straightforward to understand, and can very much be told as a story. There are heroes and bloody battles, drama and intrigues, scandals and betrayals and everything else you'd expect from a Netflix docudrama. You basically have to learn the story and acquire enough facts to be able to explain the whole thing in about 7 minutes. What I've written below is too much for what you need, so you need to construct your own shortened story. That is your main activity today.

|

Piedmont-Sardinia and the rise of Camillo di Cavour

After the failed revolutions of 1848 the remainder of Italy was once again under Hapsburg and Papal control. In 1852 Camillo di Cavour came to power as the Prime Minister at the head of a coalition of middle-class politicians and immediately set to work by all means, constitutional and otherwise, to modernise Piedmont- Sardinia. To Cavour's way of thinking, if Piedmont-Sardinia was to play a leading role in any future Italian nation-state, the region must first industrialise its economy and modernise its administration. |

He oversaw the expansion of international trade, concluding agreements with a number of European states. Railway construction increased drastically during his years in power. Textiles industries—silk, cotton and woollens—also thrived.

The Crimean War, 1853-56

The Crimean War, 1853-56

|

The Crimean War finally broke the conservative balance of power constructed at the Congress of Vienna. The resulting instability made possible the creation of modern Italy and Germany for it was foreign affairs as much as German and Italian affairs that would determine the shape of these two nation-states.

The Ottoman Empire had been in decline for a hundred years. The Ottoman Empire controlled the key maritime route between Central Europe and the Mediterranean— the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus. If Russia had designs on sea access to the west, it would have to control these two straits. When Russian forces occupied the Danubian principalities in July of 1853, The Ottoman Empire declared war. France and Britain supported the Turks against the Russians. What Cavour did next was central to the creation of the future nation-state of Italy. Cavour understood that if Piedmont-Sardinia was to draw other Italian states into a larger union he would need to have the backing of at least some of the major powers against Austria. He sought to gain the support of the French by supplying 18,000 Piedmontese soldiers. In contrast, the Crimean war drastically weakened Austria's position in Europe. It had allowed foreign powers to decide issues on Austria's borders, and shown it to be militarily too weak to intervene against Russia. Cavour had been at the peace negotiations at the end of the war and his modernised army had now had experience. Both Cavour and Napoleon III of France saw an opportunity in this new situation. |

The War of 1859

Napoleon III wanted to show himself as a moderniser of Europe against the old conservative version established at Vienna and now defended by the weakening powers of Russia and Austria. The nation-building ambitions of Cavour seemed an ideal opportunity. At a secret conference at Plombieres in July 1858 Cavour and Napoleon concluded an alliance and a plan for the future war with Austria. The plan was to provoke a war, jointly defeat Austria in battle and construct a federal Italian nation-state. Napoleon would attempt to isolate Austria diplomatically and Cavour would provoke Austria into war. For her efforts, France would receive Savoy and Nice. The resulting war went well for Cavour; Austrians left Lombardy after French victories at Magenta and Solferino in June 1859 (see work in 11e). But concerned about the possible Prussian intervention Napoleon III concluded a separate peace with the Austrians at Villafranca in July 1859. Cavour was disappointed with the result. Lombardy would be given to Piedmont. Venetia would remain in Austrian hands. The Central Duchies of Tuscany, Modena, and Parma would also remain under their traditional leaders—the Hapsburgs. Savoy and Nice would remain with Piedmont.

Napoleon III wanted to show himself as a moderniser of Europe against the old conservative version established at Vienna and now defended by the weakening powers of Russia and Austria. The nation-building ambitions of Cavour seemed an ideal opportunity. At a secret conference at Plombieres in July 1858 Cavour and Napoleon concluded an alliance and a plan for the future war with Austria. The plan was to provoke a war, jointly defeat Austria in battle and construct a federal Italian nation-state. Napoleon would attempt to isolate Austria diplomatically and Cavour would provoke Austria into war. For her efforts, France would receive Savoy and Nice. The resulting war went well for Cavour; Austrians left Lombardy after French victories at Magenta and Solferino in June 1859 (see work in 11e). But concerned about the possible Prussian intervention Napoleon III concluded a separate peace with the Austrians at Villafranca in July 1859. Cavour was disappointed with the result. Lombardy would be given to Piedmont. Venetia would remain in Austrian hands. The Central Duchies of Tuscany, Modena, and Parma would also remain under their traditional leaders—the Hapsburgs. Savoy and Nice would remain with Piedmont.

|

The Central Duchies

Just when it seemed that Italian nation-building had stopped, it was revived, not in Piedmont, but rather in the Central Duchies. When the war of 1859 broke out, the rulers of the Duchies fled to Austria and were replaced by nationalist governments. French troops occupied the Duchies to supervise popular plebiscites (referenda) on the issue of annexation to Piedmont. For his trouble, Napoleon received the previously promised Savoy and Nice. After the results of the plebiscites were tallied in March 1860 it surprised no one that the duchies with the added Papal territory of Bologna had voted overwhelmingly to join Piedmont-Sardinia. This first phase of Italian unification was a major success for Cavour and his diplomacy. He had only been denied Venetia and had unexpectedly won the Central Duchies and a portion of the Papal States. The period from 1858-60 also illustrated the extent to which the nation-building projects of the mid-19th century were just as much European concerns as they were either domestic Italian or German concerns. As such, war remained and would continue to remain a vital tool in the construction of modern Italy and Germany. |

Naples, Southern Italy and the Papal States

The island of Sicily rose up once again in rebellion against its Bourbon rulers in April 1860. The issues in Sicily were not so much about nationalism as about local class-based concerns. The revolt was led by radical republicans for whom neither Cavour nor Napoleon III had any sympathy. The nationalist revolutionary Garibaldi however, was sympathetic to the cause. He organised 1,000 volunteers from the north to join in the insurrection and liberate the island from its Neapolitan overlords.

The island of Sicily rose up once again in rebellion against its Bourbon rulers in April 1860. The issues in Sicily were not so much about nationalism as about local class-based concerns. The revolt was led by radical republicans for whom neither Cavour nor Napoleon III had any sympathy. The nationalist revolutionary Garibaldi however, was sympathetic to the cause. He organised 1,000 volunteers from the north to join in the insurrection and liberate the island from its Neapolitan overlords.

|

Cavour had to be careful. Garibaldi might provoke a French or Austrian response which would stop his plans to seize Venetia. Cavour did not actively support, nor did he interfere when Garibaldi first captured Palermo and then crossed to the mainland, conquering all of the Kingdom of Naples by September 1860. All that remained was the Papal States.

Cavour was now faced with the very real possibility that it would be Garibaldi who completed the unification or, even worse, drag the as yet unformed nation-state into a disastrous war against France or Austria. |

In a bold move to regain the initiative, Cavour invaded the Papal States. Cavour's army reached the northern border of Naples and prepared to confront Garibaldi's popular army. As he faced the Piedmontese army Garibaldi also faced the ugly prospect of civil war. To avoid such a breech in Italian national unity, Garibaldi turned Naples and the Island of Sicily over to Victor Emmanuel the annexation of which was soon confirmed by plebiscite. There was, however, the important question of those territories not included in the new Kingdom, Italia Irredenta (Unredeemed Italy), most importantly Rome and Venetia.

|

Garibaldi's visit to London in 1864

This has nothing to do with the unification but it does offer us a fascinating insight into the development of popular culture and national news media in England during the industrial revolution. (Matu 4) In 1864, an estimated half a million people came on the streets of London to greet Garibaldi. The whole country went Garibaldi crazy. He was the world's first popular celebrity, a genuine superstar made by the media. The impact of Garibaldi is still to be found in Britain today. Nottingham Forest F.C. chose their club colours from the uniform worn by Garibaldi's Redshirts, there are still at least eight pubs named after him and the Garibaldi biscuit is a personal favourite of mine.

See here here for the original Guardian report from 1864. |

Completing the unification

Italia irredenta could not be solved with parliamentary motions or unilateral Italian military action. With Napoleon's garrison protecting Rome and the Austrian possession of Venetia, including these territories into the Italian state needed to involve one or more of Europe's major powers. An opportunity for just such an involvement presented itself as Prussia and Austria drifted towards war in the period between 1864 and 1866. Where Cavour had turned to France for military help against Austria in 1859, Prime Minister Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora turned, in 1866, to Prussia. Otto von Bismarck hoped that an alliance with Italy would divert some Austrian troops to the south. In exchange for Italy's military support, Prussia would diplomatically support Italy's claim to Venetia. The war went poorly for the Italians, suffering defeat on both land and sea. Nevertheless, the Prussian victory over the Austrians was so complete that Venetia was ceded to Italy.

Similarly, the addition of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy was made possible by an impressive Prussian military victory. When Napoleon's forces were defeated by the Prussians at Sedan in September of 1870, the French garrison protecting the Pope was recalled to France. With the agreement of the major Catholic powers of Europe, the Italian army occupied Rome that same month. But would not be until 1929 that the Vatican would recognise the legitimacy of the Italian state. For its part, the Italian government gave the Pope sovereignty over Vatican City and paid him a yearly allowance. The Vatican also maintained its control of education in Italy.

Problems after unification-, ‘we have made Italy; now we must make Italians.’ Massimo d'Azeglio

North and south remained divided, politically, socially and economically. Language, currency, weights and measures, legal codes, tax and tariff structures all varied from one end of the country to the other. The perception in the south that they were second-class residents in an Italy dominated by the north created a great deal of resentment. The revolutionaries who flocked to Garibaldi's banner fought for some form of autonomy and were now under the impression that they had simply traded Austrian domination for that of the Piedmontese. In the north, where many of the politicians and most of the civil administrators came from, there was a persistent feeling that they had done all of the hard work in the creation of Italy and continued to drive the economy, supporting the inefficient and backward southern provinces. As with all such complaints there was a measure of truth in each of these perceptions. Industry was centred in the north and the south remained reluctant to reform land ownership and agriculture. The north did dominate the political culture of the state to the resentment of southerners. Victor Emanuel II, of the northern House of Savoy, had moved seamlessly to the throne of a united Italy, creating some resentment in other parts of the peninsula.

This lack of a national unity went deeper than north-south resentment. Deeply entrenched localism and regionalism meant that loyalties to this new creation called Italy often ran a distant third or fourth in the case of devout Catholics. Inadequate communication and transportation further exacerbated these divisions. Nationalism in Italy had been far more of an idea of middle-class intellectuals, than it had ever been a feeling deeply held by the majority of the peninsula's population. There still existed important Italian-speaking territories outside the Italian state. Italians made up the majority of the population in the Austrian controlled Trentino and along the Adriatic coast centred in the cities of Fiume and Trieste. More radical views of Italia irredenta also claimed a number of islands in the Adriatic and Mediterranean. In the years following unification, irredentism became an important plank in the platform of Italian nationalist parties.

Italia irredenta could not be solved with parliamentary motions or unilateral Italian military action. With Napoleon's garrison protecting Rome and the Austrian possession of Venetia, including these territories into the Italian state needed to involve one or more of Europe's major powers. An opportunity for just such an involvement presented itself as Prussia and Austria drifted towards war in the period between 1864 and 1866. Where Cavour had turned to France for military help against Austria in 1859, Prime Minister Alfonso Ferrero La Marmora turned, in 1866, to Prussia. Otto von Bismarck hoped that an alliance with Italy would divert some Austrian troops to the south. In exchange for Italy's military support, Prussia would diplomatically support Italy's claim to Venetia. The war went poorly for the Italians, suffering defeat on both land and sea. Nevertheless, the Prussian victory over the Austrians was so complete that Venetia was ceded to Italy.

Similarly, the addition of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy was made possible by an impressive Prussian military victory. When Napoleon's forces were defeated by the Prussians at Sedan in September of 1870, the French garrison protecting the Pope was recalled to France. With the agreement of the major Catholic powers of Europe, the Italian army occupied Rome that same month. But would not be until 1929 that the Vatican would recognise the legitimacy of the Italian state. For its part, the Italian government gave the Pope sovereignty over Vatican City and paid him a yearly allowance. The Vatican also maintained its control of education in Italy.

Problems after unification-, ‘we have made Italy; now we must make Italians.’ Massimo d'Azeglio

North and south remained divided, politically, socially and economically. Language, currency, weights and measures, legal codes, tax and tariff structures all varied from one end of the country to the other. The perception in the south that they were second-class residents in an Italy dominated by the north created a great deal of resentment. The revolutionaries who flocked to Garibaldi's banner fought for some form of autonomy and were now under the impression that they had simply traded Austrian domination for that of the Piedmontese. In the north, where many of the politicians and most of the civil administrators came from, there was a persistent feeling that they had done all of the hard work in the creation of Italy and continued to drive the economy, supporting the inefficient and backward southern provinces. As with all such complaints there was a measure of truth in each of these perceptions. Industry was centred in the north and the south remained reluctant to reform land ownership and agriculture. The north did dominate the political culture of the state to the resentment of southerners. Victor Emanuel II, of the northern House of Savoy, had moved seamlessly to the throne of a united Italy, creating some resentment in other parts of the peninsula.

This lack of a national unity went deeper than north-south resentment. Deeply entrenched localism and regionalism meant that loyalties to this new creation called Italy often ran a distant third or fourth in the case of devout Catholics. Inadequate communication and transportation further exacerbated these divisions. Nationalism in Italy had been far more of an idea of middle-class intellectuals, than it had ever been a feeling deeply held by the majority of the peninsula's population. There still existed important Italian-speaking territories outside the Italian state. Italians made up the majority of the population in the Austrian controlled Trentino and along the Adriatic coast centred in the cities of Fiume and Trieste. More radical views of Italia irredenta also claimed a number of islands in the Adriatic and Mediterranean. In the years following unification, irredentism became an important plank in the platform of Italian nationalist parties.

Activities

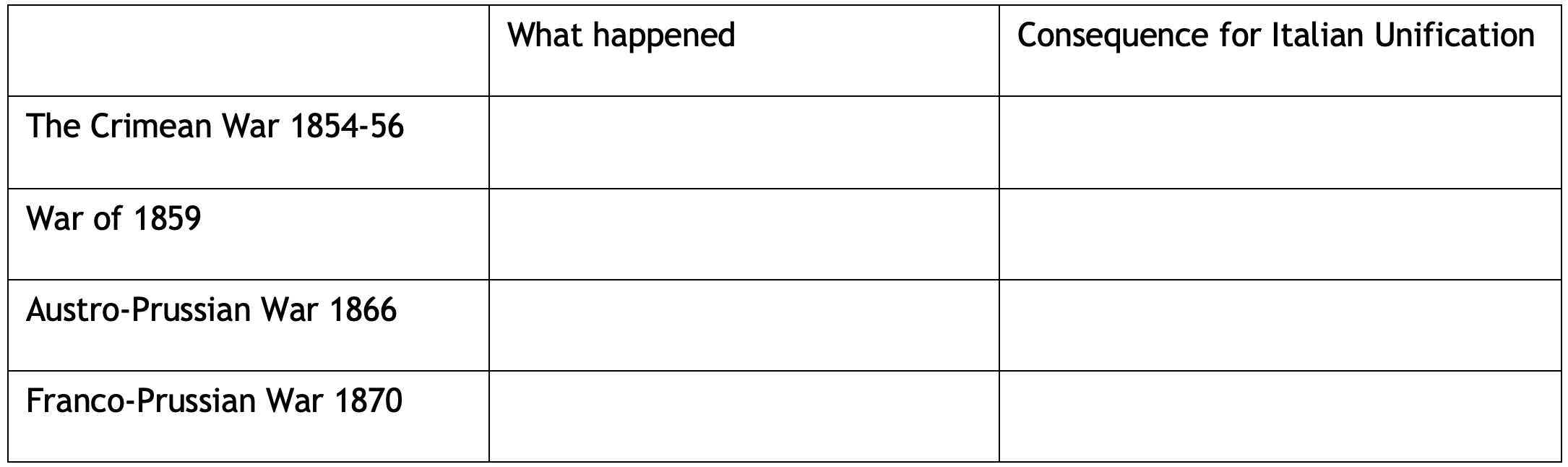

1. Copy and complete the following table to show how war was central to Italian unification.

1. Copy and complete the following table to show how war was central to Italian unification.

2. Did popular nationalism and industrial development play any role in Italian unification? Explain your answer.

3. What did Massimo d'Azeglio mean when he said ‘we have made Italy; now we must make Italians’?

3. What did Massimo d'Azeglio mean when he said ‘we have made Italy; now we must make Italians’?