Lesson 5 - How did Mussolini gain support from policies and what did he aim to achieve?

The last two lessons on the rise to power and consolidation of power of Mussolini have concentrated on the the use of formal and informal social control (coercion and persuation). This lesson shifts the focus to look at the things Hitler did that were designed to win the support of the Soviet people, that is their consent. In realty though coercion, persuasion and consent are present at all times in the relationship between the state and the individual. The first film below should remind you of the coercion, persuasion and consent model. The other two films try to explain the two different forms of consent that operate: explicit and implicit. As we will see later, the more totalitarian a state is, the more important is the expected level of explicit consent.

|

|

|

|

|

|

On coming to power Mussolini’s Fascists had a broad appeal. Fascism had its believers; it was an untested ideology that enjoyed the attraction of the new and modern. On the radical left, Fascism could be attractive with its promises to reform capitalism in the interest of the working classes. It is worth remembering that Mussolini had once been a prominent socialist. The broad concept of a ‘La terza via fascista’ promised a third way between free market capitalism and Bolshevik communism. According to the ‘third way’ ideal, fascism was supposed to replace class conflict with class harmony. It should have brought equal benefits to employers and employees, working in partnership for the good of the nation, the state and the Italian people. In particular, it was claimed that workers would no longer be exploited, and would enjoy an improved status under the ‘corporate’ state. In reality, as in Nazi Germany later, the socialist styled policies of radical fascism were marginalised, along with their supporters, as the authoritarian state consolidated its power.

|

On the traditional conservative right, Mussolini generally did far more to accommodate and co-opt important influences like the Catholic church, big business and the great landowners. In 1922, a law was introduced to split the large estates and redistribute the land, this appealed to the 'socialist' left of the Fascsist Party but this was never acted on. Agricultural wages dropped by more than 30 per cent during the 1930s. Industrialists benefitted from the Vidoni Pact of 1925 and the Charter of Labour of 1927 that increased the power and freedom of employers. United in their opposition to socialism and organised labour, traditional conservatism welcomed the weakening of the working-class organisations (Trade Unions were effectively banned in 1925-6) and support that fascism gave to traditional conservative social policies that limited women’s rights or cultural policies which saw the increased influence of the Catholic Church. (See social and cultural policies below). The lower middle classes who entered the administrative bureaucracy of the growing state or the Fascist Party enjoyed relative prosperity, with good wages and considerable benefits, as well as the opportunity to increase their income through corrupt means.

Economic Policies

Historians disagree on whether there was a distinctive fascist economic policy. Fascism’s anti-intellectualism and embrace of pragmatic realpolitik meant that fascist leaders expected the economy to serve nationalist and imperialist goals. If there was a distinctive Fascist economic policy, it was that Italy should become economically self- sufficient in both food and in raw materials for industry. This policy is known as autarky and is something that Hitler also encouraged in Germany. Although this goal was consistent, policies were inevitably weakened by the Great Depression.

In the 1920s Mussolini launched a series of bold and ambitious, state led campaigns or ‘battles’: in 1924 the Battle over the Southern Problem; in 1925 the Battle for Grain; in 1926, the Battle for Land and the Battle for the Lira. The results were mixed. Focusing resources on one problem often resulted in unexpected consequences or problems for those areas neglected by state intervention. Although the Battle for Grain succeeded in almost doubling cereal production by 1939, making Italy self-sufficient in wheat, it also involved misallocation of resources. This resulted in Italy having to import olive oil, while exports of fruit and wine, and numbers of cattle and sheep, dropped. The Battle for the Lira, which involved artificially raising the value of the lira, also resulted in declining exports — and thus increased unemployment — as Italian goods became more expensive.

Historians disagree on whether there was a distinctive fascist economic policy. Fascism’s anti-intellectualism and embrace of pragmatic realpolitik meant that fascist leaders expected the economy to serve nationalist and imperialist goals. If there was a distinctive Fascist economic policy, it was that Italy should become economically self- sufficient in both food and in raw materials for industry. This policy is known as autarky and is something that Hitler also encouraged in Germany. Although this goal was consistent, policies were inevitably weakened by the Great Depression.

In the 1920s Mussolini launched a series of bold and ambitious, state led campaigns or ‘battles’: in 1924 the Battle over the Southern Problem; in 1925 the Battle for Grain; in 1926, the Battle for Land and the Battle for the Lira. The results were mixed. Focusing resources on one problem often resulted in unexpected consequences or problems for those areas neglected by state intervention. Although the Battle for Grain succeeded in almost doubling cereal production by 1939, making Italy self-sufficient in wheat, it also involved misallocation of resources. This resulted in Italy having to import olive oil, while exports of fruit and wine, and numbers of cattle and sheep, dropped. The Battle for the Lira, which involved artificially raising the value of the lira, also resulted in declining exports — and thus increased unemployment — as Italian goods became more expensive.

|

Before the Depression, Mussolini had not interfered with private enterprise and had favoured large companies and heavy industry. However, once the Depression started to take effect, he began to consider some state intervention. The Institute per la Reconstruzione Industriale (IRI), was set up in 1933. At first, it took over various unprofitable industries on behalf of the state. By 1939, the IRI had become a massive state company, controlling most of the iron and steel industries, merchant shipping, the electrical industry and even the telephone system. However, Mussolini never intended for these industries to be permanently nationalised. Parts were regularly sold off to larger industries still under private ownership, resulting in the formation of huge capitalist monopolies. Examples of this were the large firms Montecatini and SINAViscasa, which ended up owning the entire Italian chemical industry.

As Mussolini involved Italy in more military actions, the push for autarchy increased — as did the problems associated with this struggle for self-sufficiency. Nonetheless, there were some moderate achievements: by 1940, for example, industrial production had increased by 9 per cent. As a result, industry overtook agriculture as the largest proportion of GNP for the first time in Italy’s history. In addition, between 1928 and 1939, imports of raw materials and industrial goods dropped significantly. Overall, however, fascist economic policy did not result in a significant modernisation of the economy, or even increased levels of productivity. Italy experienced a much slower recovery from the Depression than most other European states. Once Italy became involved in the Second World War, its economic and industrial weaknesses grew increasingly apparent.

|

Social Policies

The promises that had been made about the corporate state failed to materialise. Instead of ending class conflict, Mussolini’s fascist state merely prevented workers from defending their interests, while employers were able to manage their companies without either interference from the state or opposition from their employees. For example, as the economy began to decline in the second half of the 1920s, employers ended the eight-hour day and extended the working week. At the same time, wages were cut — from 1925 to 1938, the level of real wages dropped by over 10 per cent. Workers were afraid of protesting about their working conditions in case they lost their jobs altogether. Some social welfare legislation was passed in the fascist era, including the introduction of old-age pensions and unemployment and health insurance. There was also a significant increase in education expenditure. However, these improvements did not make up for the loss of wages and poor working conditions experienced by many. Mussolini’s policies clearly benefited large landowners rather than small farmers and agricultural labourers. In an attempt to escape rural poverty, many Italians emigrated. Over 200,000 Italians moved to the USA in the period 1920—29.

The promises that had been made about the corporate state failed to materialise. Instead of ending class conflict, Mussolini’s fascist state merely prevented workers from defending their interests, while employers were able to manage their companies without either interference from the state or opposition from their employees. For example, as the economy began to decline in the second half of the 1920s, employers ended the eight-hour day and extended the working week. At the same time, wages were cut — from 1925 to 1938, the level of real wages dropped by over 10 per cent. Workers were afraid of protesting about their working conditions in case they lost their jobs altogether. Some social welfare legislation was passed in the fascist era, including the introduction of old-age pensions and unemployment and health insurance. There was also a significant increase in education expenditure. However, these improvements did not make up for the loss of wages and poor working conditions experienced by many. Mussolini’s policies clearly benefited large landowners rather than small farmers and agricultural labourers. In an attempt to escape rural poverty, many Italians emigrated. Over 200,000 Italians moved to the USA in the period 1920—29.

|

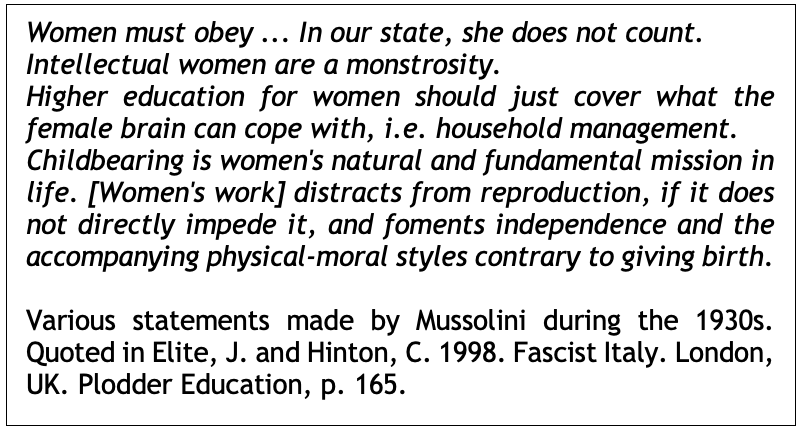

(i) Women and families

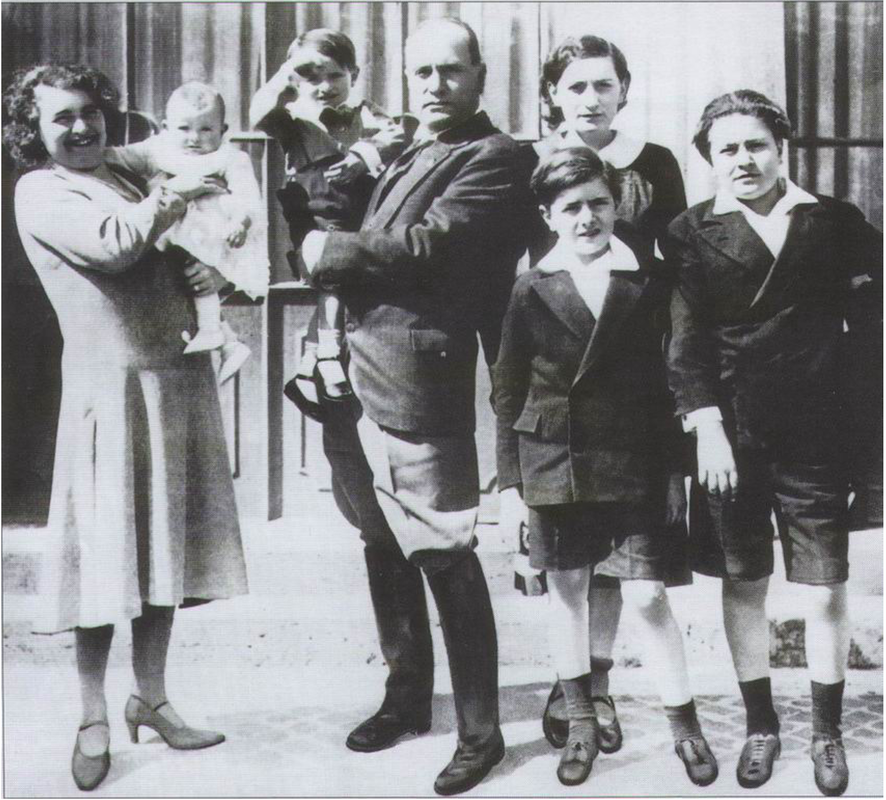

One group that suffered more than most under fascism was women. Their status was deliberately and consistently downgraded, especially by the Battle for Births, which stressed the traditional role of women as housewives and mothers and caused a downturn in employment opportunities for women. The Battle for Births was launched in 1927, in an attempt to increase the Italian population to create a large future army that would help to expand Italy’s empire. Mussolini aimed to increase the population from 40 million in 1927 to 60 million by 1950. To achieve this, the fascists encouraged early marriage, offered generous maternity benefits, and gave jobs to married fathers in preference over single men. They also gave prizes to those women in each of Italy’s ninety-three provinces who had the most children during their lives. |

|

Taxation policy was also used to encourage large families. Bachelors (especially those between the ages of thirty-five and fifty) had to pay extra taxes, while couples with six or more children paid none. Newly married couples were given cheap railway tickets for their honeymoon. Later, in 1931, same-sex relations were outlawed, and new laws against abortion and divorce were imposed. A series of decrees was imposed to restrict female employment. In 1933, it was announced that only 10 per cent of state jobs could be held by women; in 1938, this was extended to many private firms. Although this policy was partly intended to solve the problem of male unemployment, it was also a reflection of fascist attitudes towards women. It is important to note that the two key fascist policies relating to women (increasing the birth rate and reducing the number of women in the workforce) both failed to meet their targets. The number of births actually declined - dropping from 29.9 per 1,000 in 1925 to 23.1 in 1940. In addition, and as was also the case in Germany nearly one-third of Italy’s paid workforce was still female by 1940. In part, this was because Mussolini’s military adventures resulted in the conscription of large numbers of men.

|

(ii) The Church, racism and anti-Semitism

The Catholic hierarchy was particularly pleased by the fascists’ defeat of the socialists and communists and saw benefits in ending the conflict between Church and state. The real breakthrough, however, came in 1929, following a series of secret negotiations between the fascists and Cardinal Gasparri, a senior Vatican official. These negotiations resulted in three Lateran Agreements, which finally ended the conflict and bitterness that had existed between the papacy and the Italian state since 1870. By the terms of the Lateran Treaty, the government accepted papal sovereignty over Vatican City, which became an independent state.

The Catholic hierarchy was particularly pleased by the fascists’ defeat of the socialists and communists and saw benefits in ending the conflict between Church and state. The real breakthrough, however, came in 1929, following a series of secret negotiations between the fascists and Cardinal Gasparri, a senior Vatican official. These negotiations resulted in three Lateran Agreements, which finally ended the conflict and bitterness that had existed between the papacy and the Italian state since 1870. By the terms of the Lateran Treaty, the government accepted papal sovereignty over Vatican City, which became an independent state.

|

In return, the pope formally recognised the Italian state, and its possession of Rome and the former papal states. The treaty agreed that Roman Catholicism would be the official state religion of Italy, with compulsory Catholic religious education in all state schools, and that the state would pay the salaries of the clergy. In return, the papacy agreed that the state could veto the appointment of politically hostile bishops, and that the clergy should not join political parties. It was also agreed that no one could get divorced without the consent of the Church, and that civil marriages were no longer necessary. While the Lateran Agreements meant that Catholicism remained a potential rival ideology to fascism, thus preventing the establishment of a truly totalitarian dictatorship, Mussolini was satisfied. The pope and the Catholic Church gave its official backing to him as II Duce

|

While neither explicit racism nor anti-Semitism were characteristics of the early fascist movement, there was a general racist attitude underlying the fascists’ nationalism and their plans for imperialist expansion. Racism was also a strong element in the Romanita movement Mussolini believed that the Italian‘race’ was superior to those African ‘races’ in Libya and Abyssinia. In September 1938, in the newspaper II Giornale d’Italia, Mussolini claimed that ‘prestige’ was needed to maintain an empire. This, he said, required a clear ‘racial consciousness’ that established ideas of racial ‘superiority’.

Until 1936, when Mussolini joined Nazi Germany in the alliance known as the Rome—Berlin Axis, (see below) anti-Semitism had not played a part in fascist politics. Mussolini’s move towards anti-Semitism was signalled in July 1938 by the issue of the ten-point Charter of Race, which was drawn up by Mussolini and ten fascist ‘professors’. The charter was followed by a series of racial laws and decrees, initiated between September and November 1938. These anti-Semitic laws excluded Jewish children and teachers from all state schools, banned Jews from marrying non-Jews, and prevented Jews from owning large companies or landed estates. The laws also expelled foreign Jews, including those who had been granted citizenship after 1919 These laws were never fully implemented in the period 1938—43, mainly because at a local level they were largely ignored by many Italians. However, they were strongly and publicly opposed by the pope. As well as the Catholic leadership, several senior fascists were unhappy about the introduction of these racial laws.

Until 1936, when Mussolini joined Nazi Germany in the alliance known as the Rome—Berlin Axis, (see below) anti-Semitism had not played a part in fascist politics. Mussolini’s move towards anti-Semitism was signalled in July 1938 by the issue of the ten-point Charter of Race, which was drawn up by Mussolini and ten fascist ‘professors’. The charter was followed by a series of racial laws and decrees, initiated between September and November 1938. These anti-Semitic laws excluded Jewish children and teachers from all state schools, banned Jews from marrying non-Jews, and prevented Jews from owning large companies or landed estates. The laws also expelled foreign Jews, including those who had been granted citizenship after 1919 These laws were never fully implemented in the period 1938—43, mainly because at a local level they were largely ignored by many Italians. However, they were strongly and publicly opposed by the pope. As well as the Catholic leadership, several senior fascists were unhappy about the introduction of these racial laws.

|

(iii) 'Fascistisation' - education and indoctrination

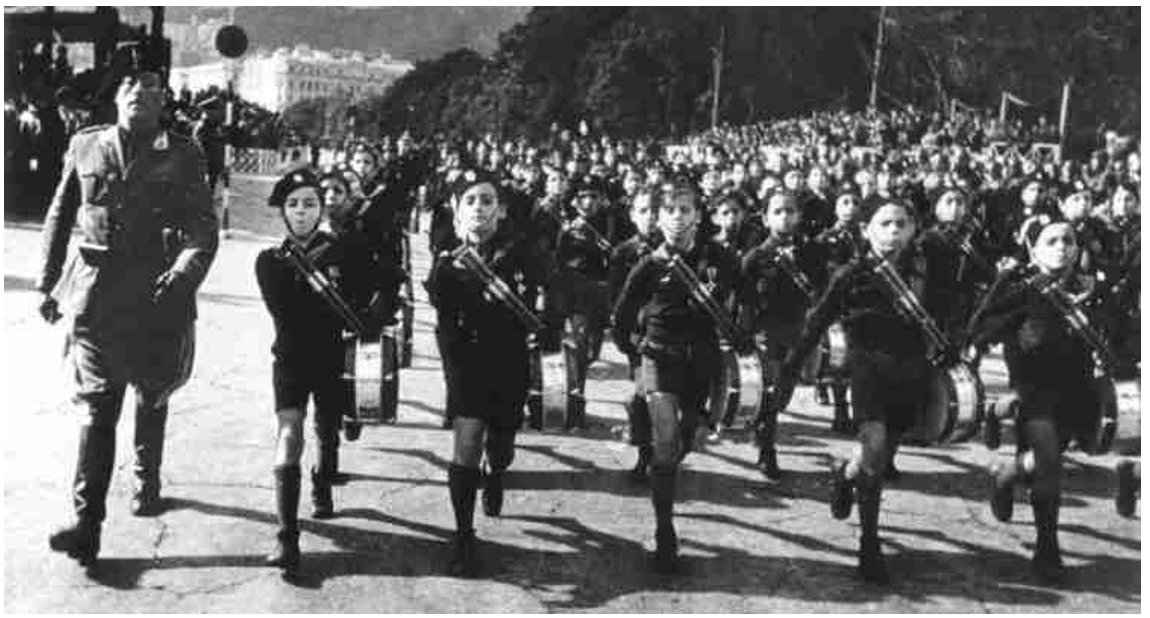

Mussolini gave prime importance to the younger generation, which - he believed - needed to be ‘fascistised’. In infant schools, children started the day with a prayer that began, ‘I believe in the genius of Mussolini’. In primary schools, children were taught that Mussolini and the fascists had ‘saved’ Italy from communist revolution. In 1929, it became compulsory for all teachers in state schools to swear an oath of loyalty to both the king and to Mussolini’s fascist regime. Two years later, this oath was extended to university lecturers. Only eleven chose to resign rather than take the oath. All school textbooks were carefully reviewed, and many were banned and replaced with new government books that emphasised the role of Mussolini and the fascists. |

The fascists also tried to indoctrinate young people by setting up youth organisations. In 1926, all fascist youth groups were made part of the Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB). Within the organisation were different sections for boys and girls, according to age. For boys, there were the Sons of the She-Wolf (4—8), the Balilla (8—14) and the Avanguardisti (14—18). For girls, there were the Piccole Italiane and the Giovani Italiane. There was also the Young Fascists for boys aged 18—21, after which they could apply to become members of the Fascist Party. By 1937, the ONB’s membership had risen to over 7 million. While all groups followed physical fitness programmes and attended summer camps that included pre-military training, older children also received political indoctrination.

|

Cultural Policies

If Mussolini’s Fascist state is to be considered a totalitarian regime, the cultural ambitions of the state must extend beyond the ‘social depoliticization’ of censorship and propaganda to include state control of media and arts to promote a new sense of social being. The last time we saw this degree of ambition was during the final phase of the French Revolution and Robespierre's attempt to replace the cultural power of the Catholic Church with a cult of reason. (Matu 2 - Lesson 9) Voltaire had said, "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him". For Robespierre, the French needed to be molded into citizens who could evolve beyond their childlike religious superstitions to an understanding of the virtues of liberty and democracy. For Robespierre the ambition was to change human nature itself. For Mussolini this meant the creation of a ‘fascist man’. |

|

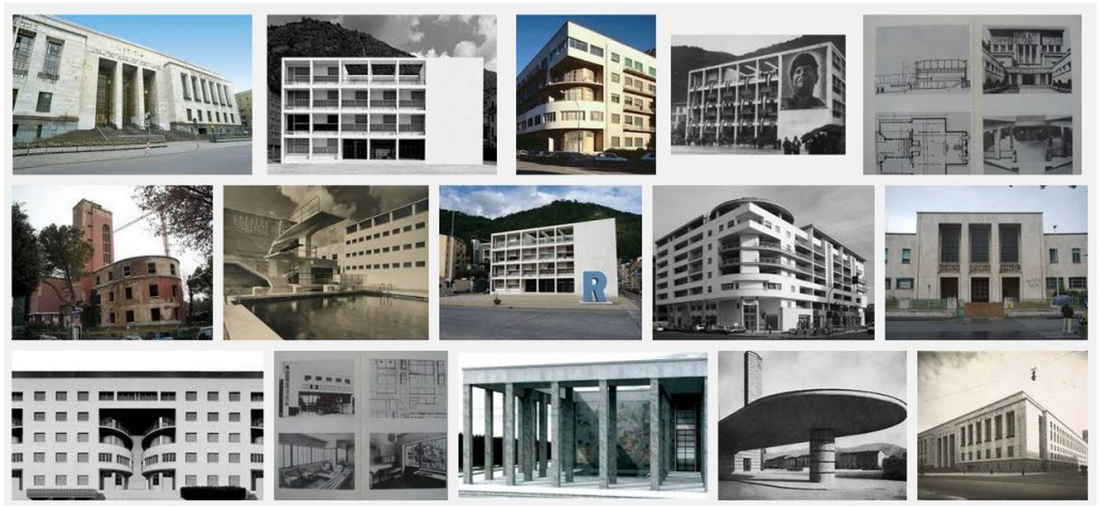

In Italy there were attempts to develop a totalitarian aesthetic, through a confused combination of modernist concrete brutalism and attempts to revive classical glories in the Romanita movement. (See the excellent Jonathan Meades documentary ‘Ben Building'). Nowhere better was this illustrated than in the war memorial at Redipuglia (see earlier documentary David Reynolds Long Shadow) Redipuglia is excessive and grand; partly because it can be, and partly because excess and size make a statement. Just like Albert Speer's New Reich Chancellery in Hitler’s Berlin or any number of the gigantic monuments to the memory of Kim Il-Sung in North Korea, the overwhelming size and purposefully imposing style is intended to inspire awe and fear in equal measure. The weakness of the individual against the power of the authoritarian state is the only message that matters.

(Above) a selection of fascist era architecture still standing in Italy today. (Below) Modernism and Romanita, The Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, also known as the Palace of Italian Civilization or simply the Colosseo Quadrato, was completed in 1937. Designed for 1942 World Fair, which was planned to be held in Rome.

From 1922 to 1943, over 700 films were produced in Italy, almost all concerned with entertainment. Although there was not the same attempt to control cinema as existed in Germany or Russia, Mussolini's son Vittorio did play a major role in the Italian film industry founding a major film school, the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (1935); and one of the world's great film production complexes, Cinecittà, inaugurated by Mussolini in 1937. But in general Mussolini's government relied on radio and short filmed documentaries prepared by LUCE (the Union of Cinematographic Education) and screened with the feature films designed for entertainment.

In contrast, popular sport was under the direct and nefarious control of Mussolini. The Italian football association was fascistised with the league centralised and new stadia built in the appropriate totalitarian style. Italy’s bid to host the 1934 World Cup and their success then (below), and four years later was directly attributed to Mussolini’s personal engagement, corruption and bribery. In 1938 he even insisted on the Italian’s wearing a black shirt.

Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (OND 1925) was a national recreational club created by the Fascist party. Its function was to increase acceptance of the fascist ideology through influencing the minds of Italy’s adult population by controlling the populations’ leisure activities. It was a network of sports clubs, libraries, organised concerts, dancing, summer holiday activities. Participation rates: 40% of industrial workers and 25% of peasants were members.

In general, social and cultural policies were far less effective than those of Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia. Italian society was far less willing to accept the imposition of state policy and did not share the other state’s traditions of effective centralised governance. There was some control in the northern cities but little if any cultural impact was made in the rural south.

Foreign Policies

The aims of his foreign policy were to gain what was called spazio vitale (‘living space’) for the Italian people, and to make Italy a great power in the Mediterranean, northern Africa and the Balkans. Although he hoped that his foreign policy would strengthen his regime, it actually ended up becoming what is generally regarded as the main factor in his downfall.

Peaceful diplomacy 1922-35

Mussolini’s use of the Corfu Incident in August 1923 is an example of how foreign policy did help him to establish and maintain power. Although, the Conference of Ambassadors eventually forced the Italians to withdraw, Greece made no official apology and Mussolini did obtain compensation from the Greeks. This increased his support within Italy and having pushed the Acerbo Law through the previous month, it was an important factor in winning a big majority in the April 1924 elections. As Mussolini was not yet in a position to achieve his aim of a great new empire by force, he followed a largely peaceful foreign policy for the next eleven years. Some aspects of this also helped to increase support for his fascist regime. For instance, in 1924, as a result of the Pact of Rome with Yugoslavia, he gained Fiume. This was a valuable port city that Italy had originally hoped to gain by the peace treaties of 1919—20 — and which had long been an aim of Italian nationalists

The aims of his foreign policy were to gain what was called spazio vitale (‘living space’) for the Italian people, and to make Italy a great power in the Mediterranean, northern Africa and the Balkans. Although he hoped that his foreign policy would strengthen his regime, it actually ended up becoming what is generally regarded as the main factor in his downfall.

Peaceful diplomacy 1922-35

Mussolini’s use of the Corfu Incident in August 1923 is an example of how foreign policy did help him to establish and maintain power. Although, the Conference of Ambassadors eventually forced the Italians to withdraw, Greece made no official apology and Mussolini did obtain compensation from the Greeks. This increased his support within Italy and having pushed the Acerbo Law through the previous month, it was an important factor in winning a big majority in the April 1924 elections. As Mussolini was not yet in a position to achieve his aim of a great new empire by force, he followed a largely peaceful foreign policy for the next eleven years. Some aspects of this also helped to increase support for his fascist regime. For instance, in 1924, as a result of the Pact of Rome with Yugoslavia, he gained Fiume. This was a valuable port city that Italy had originally hoped to gain by the peace treaties of 1919—20 — and which had long been an aim of Italian nationalists

|

Mussolini's fascist 'crusades' 1935-39

Mussolini’s preparedness to work with Britain and France ended when, later in 1935, he decided to launch fascist Italy’s first imperialist war against Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia). 500,000 Italian troops supported by bombers, tanks and poison gas faced little serious resistance. It ended the Stresa Front and Italy’s close relationship with Britain and France and moved Italy into international alignment with Germany. The growing links between fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were shown in 1936 when Mussolini informed Hitler that he would no longer object to a German Anschluss (union) with Austria and did not oppose the German reoccupation of the Rhineland. Then, on 6 March, Mussolini followed Hitler’s lead and withdrew Italy from the League. |

|

This shift to a pro-German policy was confirmed in July 1936, when Mussolini agreed to join Hitler in intervening in the Spanish Civil War to help General Francisco Franco overthrow the democratically elected Popular Front government. As in Abyssinia, Mussolini was again widely supported by a catholic nation and a pope who encouraged a ‘Christian crusade’. In October 1936, Mussolini moved closer to Nazi Germany when he signed the Rome—Berlin Axis and in December 1937, when Mussolini joined Germany and Japan in their Anti-Comintern Pact. These steps would soon prove a disaster for Mussolini and his regime.

The Second World War

Italy finally entered the war on 10 June 1940 — yet Italian forces had not recovered fully from the effects of the Abyssinian and Spanish wars. This led to food shortages and a growing dissatisfaction with the fascist regime. In particular, it led to the re-emergence of the first serious signs of opposition since the late 1920s. The resulting poor performances of the Italian army in France, Greece, Yugoslavia and North Africa played a large part in Mussolini’s eventual overthrow on 24 July 1943

Italy finally entered the war on 10 June 1940 — yet Italian forces had not recovered fully from the effects of the Abyssinian and Spanish wars. This led to food shortages and a growing dissatisfaction with the fascist regime. In particular, it led to the re-emergence of the first serious signs of opposition since the late 1920s. The resulting poor performances of the Italian army in France, Greece, Yugoslavia and North Africa played a large part in Mussolini’s eventual overthrow on 24 July 1943

|

Activities

Explain why Mussolini’s regime was able to generate wide support (consent) in the 20 years after coming to power. It is important to support your answer with a wide range of examples from different policy areas. |

|

Extension and extras (essential for IB students.)

My films below provide you with a generic, conceptual overview of how consent can be manufactured in authoritarian states. My pages on the IB section of the site also provide you with more details.

My films below provide you with a generic, conceptual overview of how consent can be manufactured in authoritarian states. My pages on the IB section of the site also provide you with more details.

|

|

|

|