Lesson 5 - Switzerland 1815 – 1847 ‘Restoration’ , ‘Regeneration’ and civil war

As in much of Western Europe, post-Napoleonic Swiss history follows patterns that are divided by the landmark dates of 1830 and 1848. Some of the structural pressures were also similar. Switzerland’s industrial growth was one of the most advanced in Europe and began to transform the country economically and socially. Political liberalism that demanded constitutional and representative government and a final end to restrictive feudal laws continued to grow in influence. And Swiss nationalism, which was first important in the period before 1798, continued to spread out from the educated classes to all sectors of society.

This historic time in Swiss history is traditionally divided into two periods: ‘Restoration’ refers to the period of 1814 to 1830 and the attempts to restore the Swiss Ancien Régime (and cantonal authority). This reversed the changes imposed by centralist Helvetic Republic from 1798 and Napoleon’s compromise Act of Mediation of 1803. ‘Regeneration’ refers to the period of 1830 to 1848, when in the wake of the July Revolution in Paris, the Ancien Régime was challenged by the liberal and nationalist movement.

And yet although Swiss history appears to resemble wider European patterns at this time, there was something distinctly Swiss about the whole process of change. The forces of conservatism were not simply a feudal class of landowning aristocrats clinging on to feudal traditions that supported a traditional way of life. In Switzerland there was a regional and religious dimension to the opposition to change that resulted in particularly deep divisions. There were to be revolutions all across Europe in this period, but only Switzerland in 1847 had a genuine civil war.

1815–1830: Restoration.

As we have seen, the old elite ‘patricians’ and many of the ruling families returned to power as a result of decisions made at the Congress of Vienna. Switzerland was forced into supporting the Holy Alliance and this resulted in restrictions on the freedom of the press and an end to Swiss toleration of political refugees.

This historic time in Swiss history is traditionally divided into two periods: ‘Restoration’ refers to the period of 1814 to 1830 and the attempts to restore the Swiss Ancien Régime (and cantonal authority). This reversed the changes imposed by centralist Helvetic Republic from 1798 and Napoleon’s compromise Act of Mediation of 1803. ‘Regeneration’ refers to the period of 1830 to 1848, when in the wake of the July Revolution in Paris, the Ancien Régime was challenged by the liberal and nationalist movement.

And yet although Swiss history appears to resemble wider European patterns at this time, there was something distinctly Swiss about the whole process of change. The forces of conservatism were not simply a feudal class of landowning aristocrats clinging on to feudal traditions that supported a traditional way of life. In Switzerland there was a regional and religious dimension to the opposition to change that resulted in particularly deep divisions. There were to be revolutions all across Europe in this period, but only Switzerland in 1847 had a genuine civil war.

1815–1830: Restoration.

As we have seen, the old elite ‘patricians’ and many of the ruling families returned to power as a result of decisions made at the Congress of Vienna. Switzerland was forced into supporting the Holy Alliance and this resulted in restrictions on the freedom of the press and an end to Swiss toleration of political refugees.

|

However, almost from the beginning, the restored regimes faced challenges from reformers. As early as 1816, an economic depression caused by the return of Britain’s modern textiles industries to European markets, made life difficult for the Swiss traditional hand-loom worker. In addition, the Restoration regimes had reintroduced cantonal tolls and customs and restricted freedom of movement, all of which damaged trade.

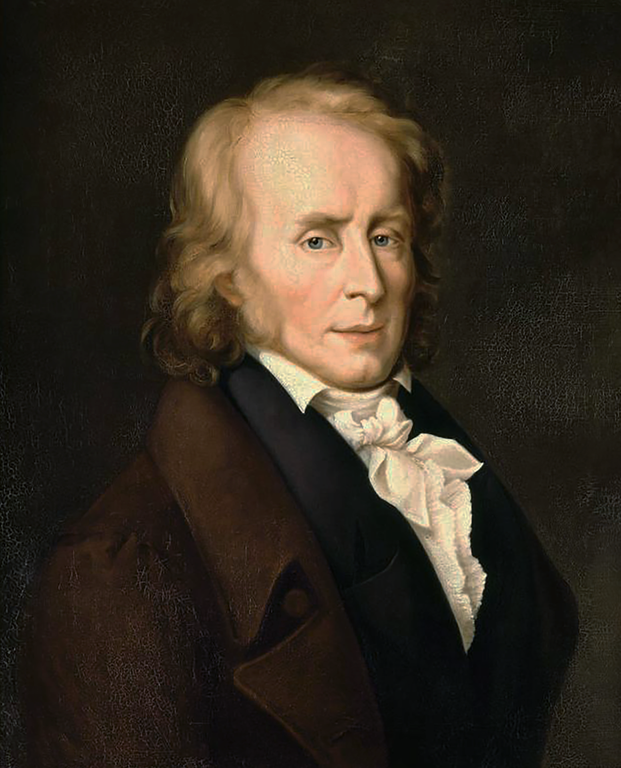

The liberal opposition demanded political and economic reform. The Vaudois liberal Benjamin Constant (lover and protégé of Germaine de Staël) wrote influential texts calling for constitutional reform to follow the English model that were inspirational to liberals throughout Europe. |

|

Benjamin Constant born in Lausanne in 1767, was one of the first political intellectuals to describe himself as 'liberal'. He considered the British form of constitutional government as the best model for modern capitalist European states.

Germaine de Staël was the daughter of Louis XVI’s banker Jacques Necker and was known for her literary salon in Paris and at Coppet. A proto- feminist who coined the word ‘romanticism’, it was said of her that there are three great powers in Europe: Britain, Russia and Madame de Staël. |

Nationalists inspired by the success of the federal army called for more national institutions to be created. The Helvetic Society was revived and played a more political role. The example of the Greek independence movement inspired romantic nationalists in Switzerland as throughout Europe.

Although the Swiss movement for political reform predated the 1830 revolutions in Europe – successful pressure and petitioning for constitutional reform had resulted in limited reform in Lucerne and Schaffhausen and significant changes in Ticino – the 1830 July revolution in Paris was a catalyst for countrywide change. Faced with countrywide demonstrations the Diet recognised the right of cantons to change their constitutions and almost all did so. Historically this is known as the ‘Regeneration’.

Although the Swiss movement for political reform predated the 1830 revolutions in Europe – successful pressure and petitioning for constitutional reform had resulted in limited reform in Lucerne and Schaffhausen and significant changes in Ticino – the 1830 July revolution in Paris was a catalyst for countrywide change. Faced with countrywide demonstrations the Diet recognised the right of cantons to change their constitutions and almost all did so. Historically this is known as the ‘Regeneration’.

|

1830-47: Regeneration

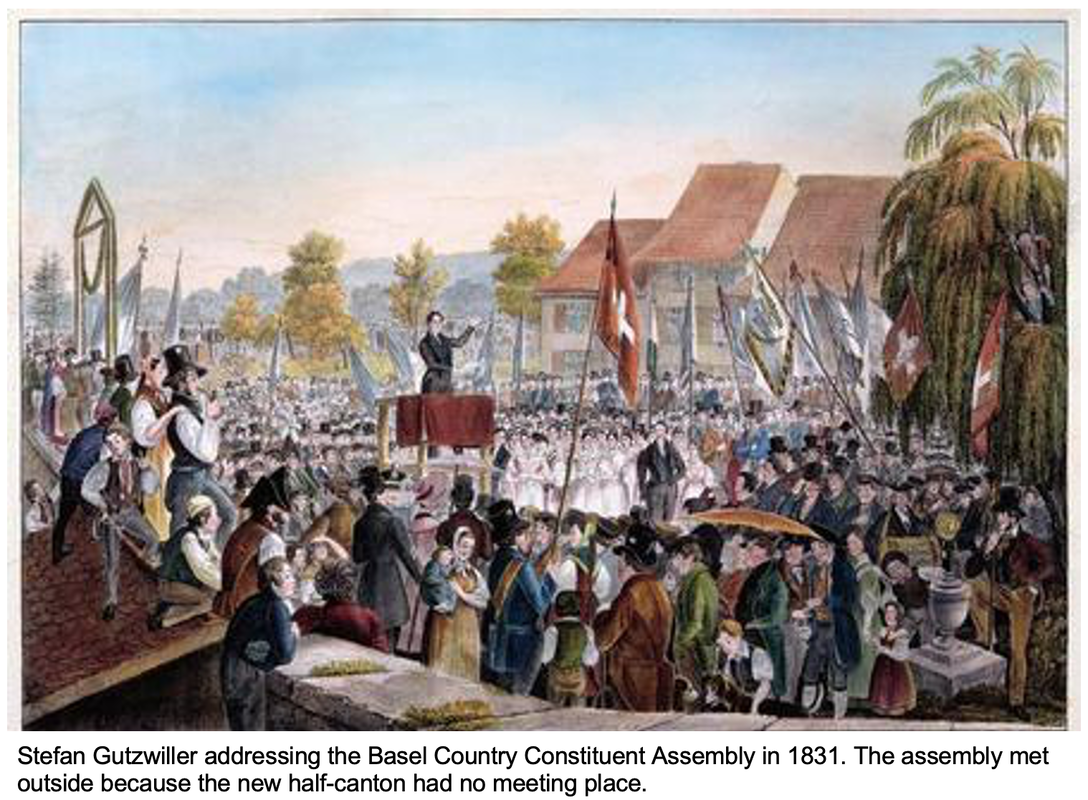

The Regeneration resulted in a swathe of classical liberal reforms being introduced across the Swiss cantons. Feudal privileges and economic restraints that had been reintroduced in 1815 were once again removed, city walls were pulled down and legislative bodies were liberalised with wider representation (more people could vote). Cantonal executives had powers reduced and terms of office were limited, censorship was ended, and new constitutions became subject to approval by popular vote. But the 1830 Regeneration did not resolve divisions in Swiss society. As with all revolutions and reform movements, there were divisions in the cantons between the reformers and conservatives and also within the reform movement itself. For example, in Basel in the 1830s, the rural population led by the lawyer Stefan Gutzwiller argued for fairer representation in the legislature. When their demands were rejected, they set up a Provisional Governing Assembly of their own in Liestal (right). |

The Basel authorities tried to break up the assembly by force but were beaten off in August 1831. The federal Diet sent soldiers to keep the two sides apart and allowed the creation of two half-cantons. The city finally accepted this division in August 1833, but only after suffering a series of military defeats in the preceding two years. A similar conflict also required federal intervention in Schwyz.

As well as divisions within cantons, there were also divisions between reformers. Many liberals were happy with the changes that had been implemented, but others wanted to go still further. Contemporaneous with the Chartist movement in Britain, these ‘advanced liberals’ or freisinnige radicals argued for the introduction of direct democracy and universal male suffrage, often as a means to improve living standards. In Switzerland, there was also an additional religious dimension, which saw the radicals calling for educational reforms intended to weaken the power of the Church. It was this religious conflict and strident and ultimately armed Catholic opposition to reform, which would ultimately push the Swiss cantons into civil war.

As well as divisions within cantons, there were also divisions between reformers. Many liberals were happy with the changes that had been implemented, but others wanted to go still further. Contemporaneous with the Chartist movement in Britain, these ‘advanced liberals’ or freisinnige radicals argued for the introduction of direct democracy and universal male suffrage, often as a means to improve living standards. In Switzerland, there was also an additional religious dimension, which saw the radicals calling for educational reforms intended to weaken the power of the Church. It was this religious conflict and strident and ultimately armed Catholic opposition to reform, which would ultimately push the Swiss cantons into civil war.

Activities

- Identify the main characteristics of the 1815-30 period of ‘Restoration’.

- What was the ‘Regeneration’? Why did it fail to resolve the divisions in Swiss society? Provide examples to illustrate your answer.

Towards civil war

As in the rest of Europe, what brought the underlying religious tensions to the surface was the economic depression of the 1840s. The Swiss economy had undergone significant change in the previous generation. As we have seen in Matu 4 textile manufacture, machine tools and chemicals had grown so that one quarter of all Swiss now worked in manufacturing. But in the 1840s these industries were hit by recession. This economic slump created social problems with which the new industrial society struggled to cope. Socio-economic discontent fuelled a desire for a political response which inevitably brought to the surface polarising religious divisions.

In 1834, six regenerated liberal cantons agreed to the Articles of Baden which set new rules for seminaries (schools for priests), marriages and feast days which were strongly opposed by conservative Swiss Catholicism. In 1837 in Zurich, peasants marched against the liberal government and after 14 people were killed an anti-radical government was put in place. Joseph Leu of Ebersoll in Lucerne led Catholic activists in the struggle against radicalism, founding the Catholic Brotherhood to defend Catholic control of education and to allow Jesuits (Catholic missionaries) into Swiss education. Catholic conservatives also fought against radical reforms in Valais and Ticino.

In 1841, Augustin Keller a liberal, initiated the rewriting of the cantonal constitution of Aargau which weakened the position of Catholics. The pro-Catholic demonstrations and anti-Catholic government retaliation led the Catholic leadership to begin discussions about organising themselves militarily. In Valais, conservatives introduced a new constitution which excluded French speakers and banned Protestantism. In 1843, Josef Leu recalled Jesuits to Lucerne.

As in the rest of Europe, what brought the underlying religious tensions to the surface was the economic depression of the 1840s. The Swiss economy had undergone significant change in the previous generation. As we have seen in Matu 4 textile manufacture, machine tools and chemicals had grown so that one quarter of all Swiss now worked in manufacturing. But in the 1840s these industries were hit by recession. This economic slump created social problems with which the new industrial society struggled to cope. Socio-economic discontent fuelled a desire for a political response which inevitably brought to the surface polarising religious divisions.

In 1834, six regenerated liberal cantons agreed to the Articles of Baden which set new rules for seminaries (schools for priests), marriages and feast days which were strongly opposed by conservative Swiss Catholicism. In 1837 in Zurich, peasants marched against the liberal government and after 14 people were killed an anti-radical government was put in place. Joseph Leu of Ebersoll in Lucerne led Catholic activists in the struggle against radicalism, founding the Catholic Brotherhood to defend Catholic control of education and to allow Jesuits (Catholic missionaries) into Swiss education. Catholic conservatives also fought against radical reforms in Valais and Ticino.

In 1841, Augustin Keller a liberal, initiated the rewriting of the cantonal constitution of Aargau which weakened the position of Catholics. The pro-Catholic demonstrations and anti-Catholic government retaliation led the Catholic leadership to begin discussions about organising themselves militarily. In Valais, conservatives introduced a new constitution which excluded French speakers and banned Protestantism. In 1843, Josef Leu recalled Jesuits to Lucerne.

|

In response, liberal cantons became increasingly radical. In 1845 Henri Druey the leader of the National Association in Vaud overthrew the liberal government for not preventing Jesuit influence. Similar radical movements came to power in power in Ticino, Zurich and Berne. When radicals failed to overthrow the conservative government in Lucerne in 1845, thousands of radical volunteers (Freischarenzug) marched on the city on two occasions but were defeated and suffered hundreds of casualties (see image opposite).

In July 1845, a freischaren soldier murdered Catholic political leader Josef Leu. In response, in December 1845, seven Catholic cantons - Lucerne, Fribourg, Valais, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug – formed a secret security pact a ‘Sonderbund’ (special alliance). As soon as it became public, ten cantons called for its dissolution, but they lacked the majority in the Diet to force the law through. This majority was finally achieved in July 1847 and the Diet called for the breakup of the Sonderbund and the expulsion of the Jesuits. In response, the Sonderbund began preparing for war. |

|

Sonderbund War 1847

The Treaty of Vienna of 1815 had guaranteed the right of the Great Powers to intervene on any Swiss change to the constitution if they all agreed it was necessary. At this point, Austria and France were conservative Catholic powers and wanted to help the Swiss conservatives. Austria remained neutral but Britain favoured the liberal cause and wanted the Jesuits expelled. Consequently, there was no significant foreign intervention, and this undoubtedly helped the liberals. (Compare this to the success and failure of other revolutions in 1830 and 1848). Colonel Jean-Ulrich de Salis-Soglio of Grisons was elected and sworn in as commander in chief of the Sonderbund army on 15 January 1847. He controlled an army of approximately 80,000. |

On 21 October 1847, the Federal Diet elected General Dufour of Geneva (right) as commander in chief of the federal army. On October 24th, 1847 the Diet ordered the mobilisation of 50,000 men, although 100,000 signed up.

|

|

The first major offensive took place in Fribourg in November which surrendered to the federal forces with little resistance. There was more significant resistance in Lucerne but the city also fell on November 27th. The other Sonderbund cantons surrendered and by the November 29th and after just 27 days, the war was over. In all, 130 soldiers had been killed.

The 20 million francs cost of the war was paid by the Sonderbund cantons and Neuchâtel and Appenzell Innerrhoden were also fined for not providing troops to the federal army. This was to the last armed conflict on Swiss territory until today. |

|

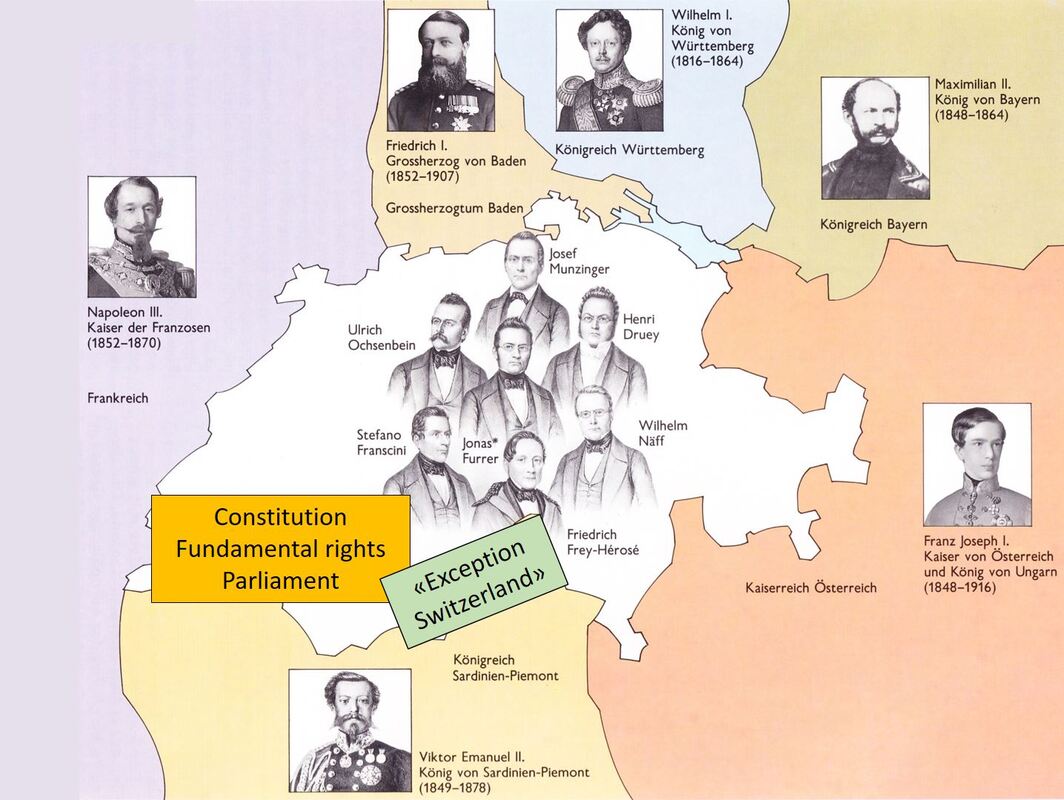

Swiss Federal Constitution 1848

In 1848, a new Swiss Federal Constitution drafted by Johann Conrad Kern of Thurgau and Henri Druey of Vaud, ended the almost-complete independence of the cantons and transformed Switzerland into a federal state. In the year of European revolutions only the Swiss succeeded in creating a democratic state. The Swiss drew up a constitution which was federal, much of it inspired by the American example. The new constitution created, for the first time, Swiss citizenship in addition to cantonal citizenship. This constitution provided for a central authority while leaving the cantons the right to self-government on local issues. The executive was the Federal Council, seven members elected by the Federal Assembly. |

|

As in the USA the Federal Assembly was divided between an upper house (the Council of States, two representatives per canton) and a lower house (the National Council, with representatives elected from across the country). N.B. The examiners are very keen on asking you to compare the two political systems.

One of the first acts of the Assembly was to choose Berne as the federal capital. Referendums were made mandatory for any amendment of this constitution. This new constitution also brought a legal end to nobility and made Switzerland a unique constitutional republic surrounded by absolute monarchs. (below right) As historian Kurt Messmer has concluded: 'Yes, it’s true: the rifts created by the Sonderbund War would take a long time to heal. Yes, it’s true: there was still no such thing as an initiative or a referendum. Yes, it’s true: 1848, was the birth of Switzerland as a nation state. But it was not yet a social state, and certainly not a state in which women could participate. Need I say more? But one thing is certain: in 1848, Switzerland had the most progressive constitution in all of Europe.'

One of the first acts of the Assembly was to choose Berne as the federal capital. Referendums were made mandatory for any amendment of this constitution. This new constitution also brought a legal end to nobility and made Switzerland a unique constitutional republic surrounded by absolute monarchs. (below right) As historian Kurt Messmer has concluded: 'Yes, it’s true: the rifts created by the Sonderbund War would take a long time to heal. Yes, it’s true: there was still no such thing as an initiative or a referendum. Yes, it’s true: 1848, was the birth of Switzerland as a nation state. But it was not yet a social state, and certainly not a state in which women could participate. Need I say more? But one thing is certain: in 1848, Switzerland had the most progressive constitution in all of Europe.'

A system of single weights and measures was introduced, in 1849 a federal postal service was introduced and in 1850 the Swiss franc became the Swiss single currency. A federal university and a polytechnic school were to be founded. The Swiss railway line was opened in 1847, connecting Zürich and Baden. In 1854 roads and canals were taken under federal control. Article 11 of the constitution forbade sending troops to serve abroad, with the exception of serving the Holy See in Rome. All Christians were guaranteed the exercise of their religion, but the Jesuits were expelled from Switzerland and this ban was only lifted on 20 May 1973. The constitutional basis for the modern Swiss state was in place.

|

(Left and popular with examiners) Scene commemorating the entry into force of the Swiss Federal Constitution on 12 September 1848. Not a revolution from above, but a constitution based on a popular vote, triumphantly proclaimed by an angel with a double fanfare. Farmers, students, merchants, academics, even soldiers and officers are there, but only one woman is present: Helvetia. The cantonal coats of arms at the bottom of this commemorative scene are not mere window-dressing, but the foundation on which the whole thing rests. The Federal Constitution does not designate the Confederation as sovereign. Article 3 states that “The Cantons are sovereign except to the extent that their sovereignty is limited by the Federal Constitution.”

|

The official sequence of cantons set down in 1848 remains in place today: first, the three former presiding cantons Zurich, Bern and Lucerne, then the others according to the year in which they became a member of the Confederation. As can be seen in the image above, starting from the middle. This is doubly significant. First because Lucerne, although on the losing side of the Sonderbund War, nevertheless retained its special status. (Kurt Messmer 2023)

Activities

3. Explain the causes of the Sonderbund war. It is important that you explain the economic context and the actions of both Catholics and Radicals.

4. Outline the main features of the Sonderbund War.

5. Summarise the main characteristics of the Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848.

More recently, RTS also produced a relatively big-budget, drama-documentary called the Swiss Civil War.

3. Explain the causes of the Sonderbund war. It is important that you explain the economic context and the actions of both Catholics and Radicals.

4. Outline the main features of the Sonderbund War.

5. Summarise the main characteristics of the Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848.

More recently, RTS also produced a relatively big-budget, drama-documentary called the Swiss Civil War.