Lesson 3 - Mussolini's Rise to Power

To supplement what I have to say and to give you a more traditional narrative overview here is a comprehensive extract from an old 'A Level' text that I used to use. Alternatively, you can watch the films below.

“History is the record of an encounter between character and circumstances.” — Donald Creighton, Canadian historian (1902-79).

In this unit we distinguish between the conditions that give rise to authoritarianian and methods used by those would be authoritarians seeking power. A more satisfactory (sociological) distinction can be made for the emergence of authoritarian states in dividing between between structural factors and the role of human agency.

In this unit we distinguish between the conditions that give rise to authoritarianian and methods used by those would be authoritarians seeking power. A more satisfactory (sociological) distinction can be made for the emergence of authoritarian states in dividing between between structural factors and the role of human agency.

|

|

|

|

Structural Factors

Structural factors refer to the context that makes the rise to power of an authoritarian state more likely. Put simply, authoritarian regimes are unusual in countries that are rich, socially stable and that have a tradition of constitutionally limited, civilian government. If they do emerge in these sorts of countries, it is usually the result of a crisis situation, brought about by external factors such as war or international economic crisis. As usual with history, PESC (+) is a good way to go about organising the structural factors. |

|

Political factors

Italy had only extended the franchise to all adult men in 1912 and up to this point governments were formed by factions that assembled around leading liberal politicians who did deals to rule amongst themselves. This process was called ‘trasformismo’ and was designed to keep mass parties, especially the socialists, out of power. Before the war this system was dominated by Giovanni Giolitti. This approach emphasized pragmatic, moderate policies and often involved compromises and patronage. The resulting public disillusionment with the self-serving nature of politics contributed to the rise of radical movements like socialism and fascism, which offered alternatives to the perceived inefficacy and corruption of the existing political system.

Italy had only extended the franchise to all adult men in 1912 and up to this point governments were formed by factions that assembled around leading liberal politicians who did deals to rule amongst themselves. This process was called ‘trasformismo’ and was designed to keep mass parties, especially the socialists, out of power. Before the war this system was dominated by Giovanni Giolitti. This approach emphasized pragmatic, moderate policies and often involved compromises and patronage. The resulting public disillusionment with the self-serving nature of politics contributed to the rise of radical movements like socialism and fascism, which offered alternatives to the perceived inefficacy and corruption of the existing political system.

|

|

Post-war Italy’s political system might be said to provide a classic example of a state suffering a legitimation crisis (Habermas). The Socialist Party (PSI), inspired by the Bolsheviks, had grown from 50,000 members in 1914 to 200,000 members by 1919 and rejected the ‘bourgeois’ nature of the Italian state. The two years at the end of the war were known as the biennio rosso. The strikes, land and factory occupations forced the government to make concessions that many on the right felt were a sign of weakness.

On the far right, the Arditi drew on support from former soldiers and nationalists. Formed in 1917, the Arditi had specialized in raiding enemy trenches and conducting high-risk assaults. |

Their name, "Arditi," translates to "the daring ones." In Milan, March 1919, under the leadership of Mussolini they formed a Fascio di Combattimento (combat group) later known as the Fascists of the First Hour.

Post-war Italy shared many of the classic characteristics of what we now call a ‘failed state.’ There were high levels of violence and the existence of extra-legal paramilitary groups throughout Italy. In November 1919 the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio led an army of 2000 to take control of Fiume, the Yugoslav port city that had been promised to Italy during the war. There was nothing the Italian government could do to stop him.

Post-war Italy shared many of the classic characteristics of what we now call a ‘failed state.’ There were high levels of violence and the existence of extra-legal paramilitary groups throughout Italy. In November 1919 the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio led an army of 2000 to take control of Fiume, the Yugoslav port city that had been promised to Italy during the war. There was nothing the Italian government could do to stop him.

|

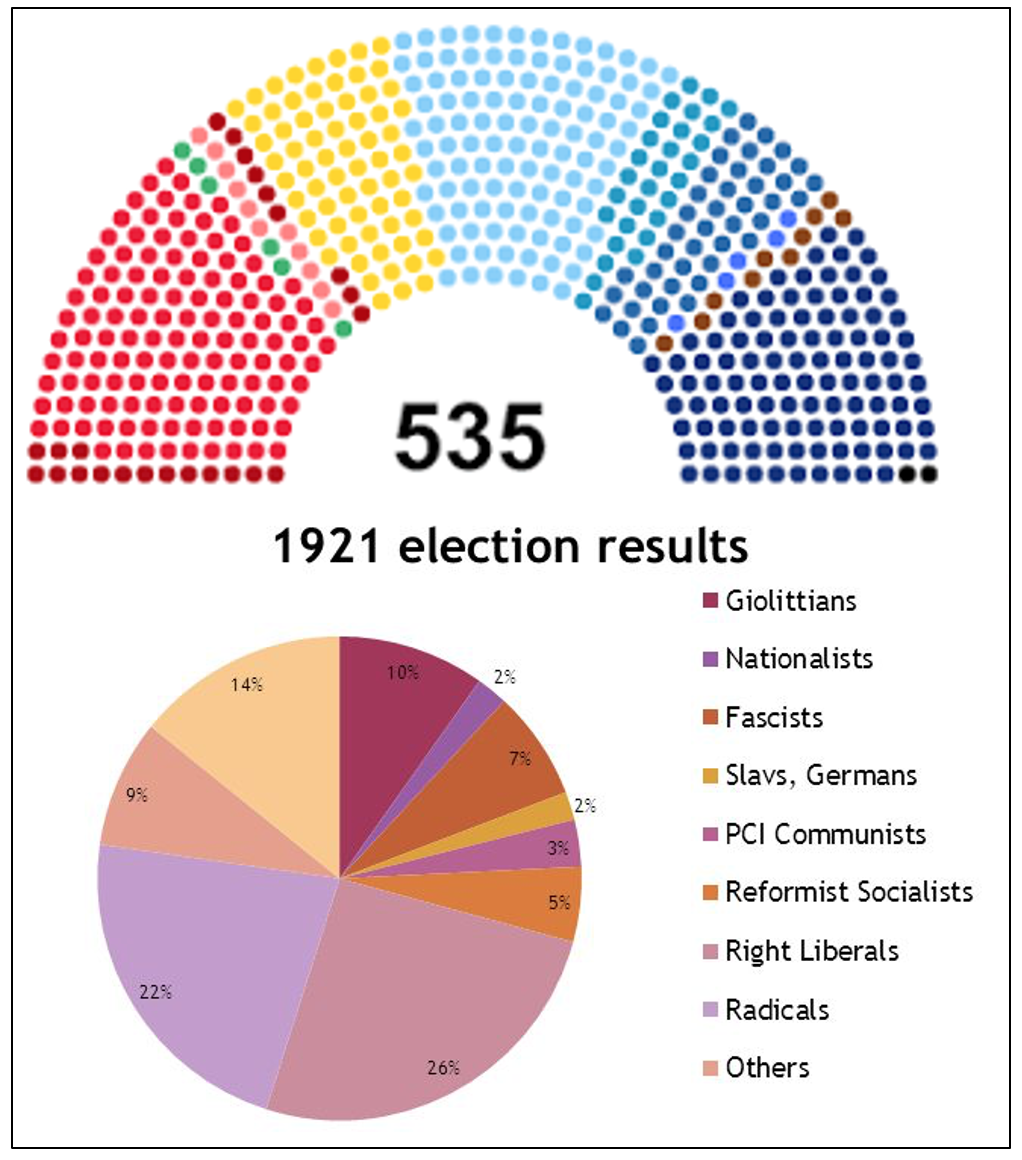

In the 1921 election for the Italian parliament, fascists squads were responsible for the deaths of over 100 socialists. (See left, click to enlarge)

Despite being the biggest party, the socialists were unable to form a government. The electoral system of proportional representation made it very difficult for one party to rule without forming a colation and also allowed smaller parties like Mussolini’s Fascists to gain parliamentary representation with only 7% of the vote. Between May 1921 and October 1922 there were three weak coalition governments that could do little in the face of industrial unrest and paramilitary violence. Mussolini’s Fascists gained a degree of respectability and a national platform. But it was their willingness to threaten organised violence and a coup d’état that persuaded the King to back down and appoint Mussolini as Prime Minister in October 1922. |

Socio-economic factors

|

Social division is concerned with how divisions between groups of people in society make it difficult for the state to peacefully manage a community of competing interests. When the economy is weak, the social divisions are accentuated. |

|

|

Although Italy had been ‘unified’ in the 1860s, it remained a deeply divided society. The north was modern and industrialised, the south was largely agricultural. In the north, a large well-organised and militant working class regularly clashed with the powerful conservative forces who ran the factories and banks. In 1919-20, the Turin factory workers councils seized control of their workplaces (see below)

|

In the south, large estates or latifundia were owned by the wealthy agrari, while most southerners were poor sharecroppers and landless labourers. The lack of social cohesion in Italy wasn’t helped by the fact that the Pope still refused to recognise the legitimacy of the Italian state which had seized the Papal lands in 1870.

As in all European countries the First World War had a devastating impact on the Italian economy. It accentuated the divisions between north and south as the iron, chemical and car industries boomed with guaranteed government contracts whilst in the south essential labourers were conscripted into the war effort. |

The Italian government borrowing from the allies resulted in an increase in national debt from 16 billion to 85 billion lire. In addition and in order to cope, the government printed more bank notes, and this resulted in inflation that saw prices rise 400% between 1915 and 1918. This not only made peoples’ savings worthless, it also caused a 25% decrease in the real wages of workers. The dislocating impact of the end of the war led to high unemployment when factories involved in war industries closed and soldiers were demobilised

|

Cultural factors

The cultural climate of post-war Italy certainly favoured the rise to power of authoritarian government. The lack of a well-established ‘participant’ or democratic political culture meant that was little understanding of or support for the sort of liberal traditions and institutions to be found elsewhere in western Europe. Instead, populist ideas in 1919 revolved around the incomplete status of the unification project; the ‘terra irredenta’, the lands that had been inhabited by Italian speakers in the former Austro-Hungarian empire. |

|

The ‘mutilated peace’ of St Germain failed to ‘return’ these lands promised by the Treaty of London in 1915 (see below). In addition, nationalist and imperial sentiments also found expression in the incomplete empire building that had begun in north Africa at the end of the 19th century. Fascism was able to draw on those sentiments and provide an ideological vision that combined these traditional conservative goals with a revolutionary vitalism, anti-leftism and the belief in a strong leader.

Democracies are what the Austrian–British philosopher Karl Popper called ‘open societies’, by which he meant societies that are open to and tolerant of, competing ideas and ways of living. Democracies, in theory, tolerate and even encourage minorities, because the social diversity that results is in itself a good thing. Karl Popper argued that ideological authoritarian states like Mussolini's Italy produce ‘closed societies’, because these ‘totalitarian ideologies’ require a quasi religious, exclusive commitment to these ideas alone. Fascism and Communism are examples of what Popper called ‘historicist’; philosophies that claim to have uncovered ‘the “rhythms” or the “patterns”, the “laws” or the “trends” that underlie the evolution of history’. (Popper, The Poverty of Historicism) If an ideology claims to have uncovered the truth about the laws of historical development, if it knows there is a future utopia to be attained, there can be no place for those who get in the way of progress. Totalitarian regimes require the public to believe, and the state must be disciplined and ruthless with those ‘minorities’ who do not.

|

The importance of the war

The First World War ended that optimism and gave rise to fascism and communism, two modern totalitarian models that stood as rivals to liberal democracy. The experience of total war was important to the rise of authoritarianism but defeat in war even more so. Of the eleven European states that had remained democracies by the time of the outbreak of the Second World War, all had either been neutral or on the winning side of the First World War. As we saw in Russia in 1914-17, war is an important condition to the emergence of authoritarian states because it has a tendency to exacerbate the other PESC factors. |

|

- War has an impact on the socio-economic ability of a state to function effectively . In addition, wartime and post-war economies struggle to adapt to changed demands, economic dislocation .

- War has an impact of the political system itself. In brief, all states that fight wars have to become more authoritarian if they are to win. Even the most liberal democracy has to centralise control over the economy, society and culture. Remember DORA in liberal Britain?

- The experience of war changes human beings. War needs individuals subsumed to the interests of the group: the nation and the fatherland. It is the emotions of patriotism and hatred of the other, not reason and empathy that are the most welcome characteristics.

As we saw in Russia in 1917 with the Kronstadt sailors, the existence of a sympathetic section of the army or a well-armed civilian population is often essential to the revolutionary capture of a state and this militarised state is most commonly found in time of war. When the new regime is established it will naturally retain some of the characteristics of its foundation: militaristic cultural values such as loyalty and discipline, a respect for military authority and military leaders reluctant to hand over authority to civilian leaders.

|

The First World War was a disaster for Italy. From the very beginning Italians were divided about why they were involved. The five million soldiers who fought were ill equipped and badly led. The disaster of Caporetto in November 1917 where 40,000 were killed and 300,000 taken prisoner became symbolic with all that was wrong with the liberal state.

As in all countries, soldiers struggled to return to normalcy after the war; the economic crisis and high unemployment often denied them a purpose to life which the army had provided. Many were attracted to the paramilitary organisations and the violent camaraderie they provided. Mussolini’s Black Shirts were an obvious attraction for many, as was their promise to undo the 'humiliation' of the Paris Peace Treaties. |

Human Agency

Structural factors can only provide a context into which historical actors are able to take decisions and make things happen. Mussolini. like Lenin was also an astute politician. His decision to support Italy joining the war in 1915 was not merely a reflection of his nationalism. It also driven by his political ambitions. Initially a socialist, he broke with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) over its stance on the war, which was largely pacifist and neutral. By advocating for intervention, Mussolini distanced himself from the PSI and positioned himself as a leader in the emerging nationalist movement, eventually founding the Fascist Party.

Many (most?) authoritarian states come to power on the back of a willingness to use violence through revolutions and coups, even if violence rarely explains everything. There is little doubt that the willingness to use violence helped Mussolini intimidate his opponents and forced the liberal government into making concessions. Violence played a significant role in Mussolini's rise to power, primarily through the actions of the Blackshirts (Squadristi), a paramilitary wing of the Fascist Party. The Blackshirts used violence to intimidate and suppress political opponents, particularly socialists, communists, and trade unionists. They disrupted meetings, attacked offices, and assaulted individuals associated with these groups.

The largely mythical ‘March on Rome’ in 1922 was typical of how the threat of violence could force political change. The Italian PM Luigi Facta had persuaded the king to use the military to prevent Mussolini from assembling in Rome. When the king changed his mind, Facta resigned as Prime Minister and created the opportunity for Mussolini to be appointed. There was no ‘march on Rome’, Mussolini arrived by train to celebratory demonstrations by the fascist militia, having been appointed the day before.

Structural factors can only provide a context into which historical actors are able to take decisions and make things happen. Mussolini. like Lenin was also an astute politician. His decision to support Italy joining the war in 1915 was not merely a reflection of his nationalism. It also driven by his political ambitions. Initially a socialist, he broke with the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) over its stance on the war, which was largely pacifist and neutral. By advocating for intervention, Mussolini distanced himself from the PSI and positioned himself as a leader in the emerging nationalist movement, eventually founding the Fascist Party.

Many (most?) authoritarian states come to power on the back of a willingness to use violence through revolutions and coups, even if violence rarely explains everything. There is little doubt that the willingness to use violence helped Mussolini intimidate his opponents and forced the liberal government into making concessions. Violence played a significant role in Mussolini's rise to power, primarily through the actions of the Blackshirts (Squadristi), a paramilitary wing of the Fascist Party. The Blackshirts used violence to intimidate and suppress political opponents, particularly socialists, communists, and trade unionists. They disrupted meetings, attacked offices, and assaulted individuals associated with these groups.

The largely mythical ‘March on Rome’ in 1922 was typical of how the threat of violence could force political change. The Italian PM Luigi Facta had persuaded the king to use the military to prevent Mussolini from assembling in Rome. When the king changed his mind, Facta resigned as Prime Minister and created the opportunity for Mussolini to be appointed. There was no ‘march on Rome’, Mussolini arrived by train to celebratory demonstrations by the fascist militia, having been appointed the day before.

‘And, however much violence may be deplored, it is evident that we, in order to make our ideas understood, must beat refractory skulls with resounding blows ... We are violent because it is necessary to be so ...’

Mussolini to the fascists of Bologna, April 1921.

Mussolini had also been a journalist. It is worth remembering that the ideas of fascism and programmes of ‘national regeneration’ were well circulated and found a wide audience. Mussolini’s speeches and the propaganda that suggested he was the strong man who could save Italy from communism; he was the Duce and the subject of songs even before the seizure of power.

|

In the end he came to power because he was widely supported, particularly by those that really mattered in Italian society. Bankers, industrialists and the agrari funded the fascist movement. The political elites ignored the violence of the fascist action squads and even provided transport to enable fascists to break up left-wing meetings. But the appeal of the fascist policies was genuinely widespread. The membership of the Fascist party grew to over 200,000 by the end of 1922. The programme was sufficiently vague to mean different things to a wide range of people: the nationalism, the anti-communism, the promise of order on the streets and economic revival spoke equally to shop keepers, bank clerks and small farmers. For many in 1922, Fascism was the future.

|

Activity

Prepare an essay plan for the end of year oral exam in answer to the question ‘how important was the First World War to the rise to power of fascism in Italy?'

Prepare an essay plan for the end of year oral exam in answer to the question ‘how important was the First World War to the rise to power of fascism in Italy?'

Extension (essential for IB students.

|

|

After Lenin's Russia this your second case study on the rise of an authoritarian state. As IB students you need to start looking out for similarities and differences between the two examples. The approach of structure and agency I have used here is developed in more detail on these IB pages. I have also made three films to explain the key concepts (below) which you have seen in edited versions above..

|

Structural factors - PESC

|

Structural factors - War

|

The role of agency.

|