Lesson 1 - What factors, both internal and external, encouraged decolonisation in Asia and Africa after 1945?

|

What is decolonisation?

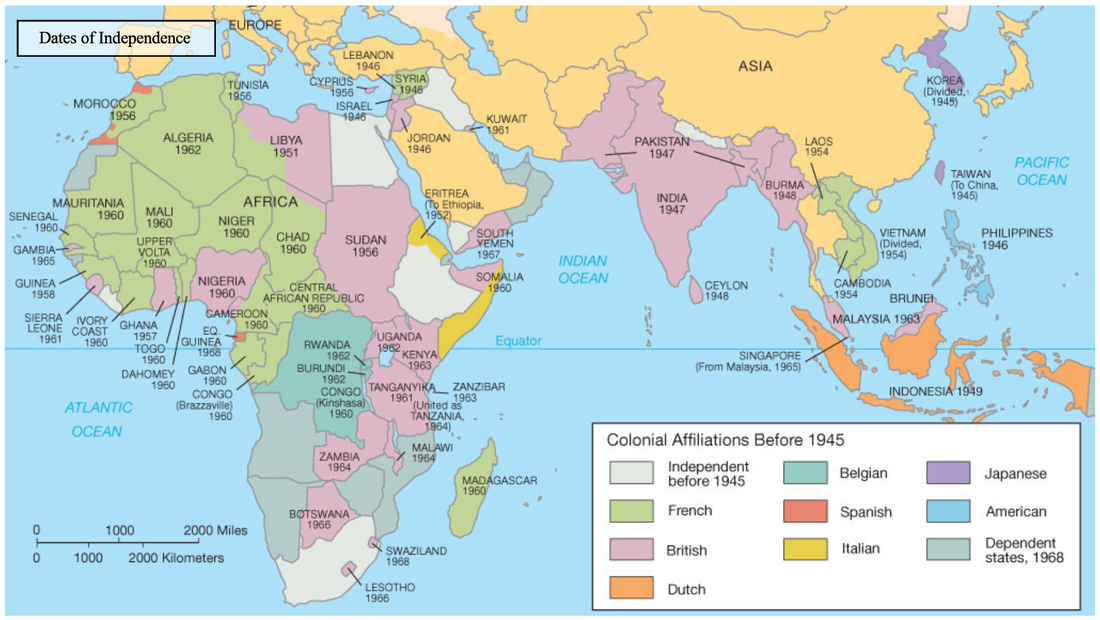

Decolonisation is the process by which dependent countries (colonies) become independent of a colonial or imperial power. ecolonisation might be said to have begun with the American Wars of Independence and continued in the 19th century with the decline of the Spanish empire in the Americas and the Ottoman Empire in Europe. The independence movements you have previously studied which led to Greek independence (1821) or Serbia (1878) might be considered earlier examples of decolonisation. |

|

After 1919

The history of the decolonisation of Asia and Africa begins with the end of the First World War, a war that had mobilised colonial armies to make common sacrifice alongside the ‘mother country’. The hope that this sacrifice might be rewarded - along with Woodrow Wilson’s principle of ‘self-determination’ and the break-up of the German overseas empire - led many anti-colonialists to anticipate that Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations might, through the ‘mandate’ system, advance the cause of decolonisation. Indeed, the Versailles Peace Conference did inspire W. E. B. Du Boise to organise the first Pan-African Congress – demanding an end to racism and colonial rule - which also took place in Paris in February 1919.

The history of the decolonisation of Asia and Africa begins with the end of the First World War, a war that had mobilised colonial armies to make common sacrifice alongside the ‘mother country’. The hope that this sacrifice might be rewarded - along with Woodrow Wilson’s principle of ‘self-determination’ and the break-up of the German overseas empire - led many anti-colonialists to anticipate that Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations might, through the ‘mandate’ system, advance the cause of decolonisation. Indeed, the Versailles Peace Conference did inspire W. E. B. Du Boise to organise the first Pan-African Congress – demanding an end to racism and colonial rule - which also took place in Paris in February 1919.

|

It also led a young Vietnamese student and member of the French Socialist Party delegate at Versailles, Ho Chi Minh, (right - who was then working as a kitchen assistant at the Hotel Ritz in Paris) to send a petition to the American delegation asking America for help to end French rule. Ho Chi Minh would not be the only one to be disappointed by the outcome of 1919, perhaps most importantly the Chinese May Fourth Movement that grew out of the anti-imperialist student movement in Beijing on May 4, 1919, protested against the Treaty of Versailles, especially the decision to allow Japan to receive former German territories.

|

The interwar period

The period up to the Second World War laid the foundations of the post-war decolonisation movement. Movements were beginning to emerge across the periphery, dedicated to achieving political independence. For example, in February 1927 the first meeting of the International Congress of the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression in Brussels declared:

The period up to the Second World War laid the foundations of the post-war decolonisation movement. Movements were beginning to emerge across the periphery, dedicated to achieving political independence. For example, in February 1927 the first meeting of the International Congress of the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression in Brussels declared:

The development of the African people was abruptly cut short and their civilisation was most completely destroyed. These nations were later declared pagan and savage, an inferior race, destined by the Christian God to be slaves to superior Europeans.

One of the first political independence movements was the Indian National Congress founded in 1885, which by 1906 had adopted the aim of swaraj or 'home rule'. In neighbouring Burma and Ceylon there were also nationalist movements, in the former under the guidance of U Ottoma, leader of the General Council of Buddhist Associations.

|

In the 1900s a nationalist movement, Sarekat Islam, was founded in the Dutch East Indies. In 1919 a delegation seeking independence for the Philippines was sent to the United States. But it was only in Egypt and India that independence movements gained any headway.

In order to contain nationalism and retain effective control, the British recognized Egypt as formally independent in 1922, but subject to conditions giving the British all the essential powers over military and foreign policy that they thought they needed. In India, the British were forced to gradually allow for increasing Indian independence through a series of reforms and declarations in 1908, 1917, 1919, 1929 and 1935. |

|

But opposition to Indian independence remained strong among the English ruling elite, their reasons for opposing decolonisation often sound bluntly racist to modern ears. For example, Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for India during the war, wrote:

If India is to be really capable of holding its own in future without direct British control from outside I am not sure that it will not need an increasing infusion of stronger Nordic blood, whether by settlement or intermarriage or otherwise. Possibly it has been a real mistake of ours in the past not to encourage Indian princes to marry English wives ... and so breed a more virile type of native ruler.

What factors, both internal and external, encouraged decolonisation and defined the experience of decolonisation after 1945?

The experience of decolonisation was not the same in every country, but to some extent this variation might be explained by the similarity and difference (and relative importance) of certain ‘factors’ of decolonisation. Although somewhat simplified we can identify three typical experiences of decolonisation.

This variation raises a number of questions that must be considered as you work through the case studies of national independence. For example, how did the different experiences of WWII influence the process of decolonisation? Or how did the level of economic and social development of the colony influence the nature of decolonisation? We might even ponder direct questions of correlation such as: is there a relationship between the nature of colonial rule and the tendency for some decolonisation experiences to end in violence?

The experience of decolonisation was not the same in every country, but to some extent this variation might be explained by the similarity and difference (and relative importance) of certain ‘factors’ of decolonisation. Although somewhat simplified we can identify three typical experiences of decolonisation.

- Violent: The transfer of power from colonial authority came about as a result of war and often long violent struggle. This was the case of the Indonesia (1949), French Indochina (1954), Algeria (1962) and Kenya (1963).

- Negotiated: Independence was achieved without brutal struggles. This includes the example of India (1947), Tunisia (1956), Ghana (1957) and Tanzania (1964).

- Accelerated: In this type of decolonisation there has been little or no preparation. This was the case of much of black Africa in the 1960s and notably the Belgian Congo (1960).

This variation raises a number of questions that must be considered as you work through the case studies of national independence. For example, how did the different experiences of WWII influence the process of decolonisation? Or how did the level of economic and social development of the colony influence the nature of decolonisation? We might even ponder direct questions of correlation such as: is there a relationship between the nature of colonial rule and the tendency for some decolonisation experiences to end in violence?

External factors - help explain the timing of the decolonisation.

An external factor of decolonisation refers to something that encouraged or made possible the process of decolonisation that was relatively ‘independent’ of the influence of either the coloniser or colonised. Often an external factor provided a context that might enable or hinder the process of decolonisation. Without doubt the most important external factor of decolonisation was the Second World War. The defeat and occupation of European colonial powers such as France and the Netherlands provided anti-colonial liberation movements with an opportunity in which both to assert their independence and fine-tune their political and military tactics, often against a new occupying power, Japan. The ultimate defeat of Japan created a power vacuum that well-established independence movements could fill and prove difficult to dislodge. Even though the most important imperial power Britain was not itself occupied during the war many of its colonies were. A second key external factor was economic. In an age of post-war austerity and international debt, Britain and other European powers often lacked the political resolve to maintain the economic burden of maintaining an empire in a Cold War age of changed priorities. Thirdly, there is little doubt that after 1945 a pro-independence/anti-colonial climate of international opinion developed that influenced even those colonies where little popular pre-war support for independence had been generated. By 1945 the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism, and delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and national activists.

An external factor of decolonisation refers to something that encouraged or made possible the process of decolonisation that was relatively ‘independent’ of the influence of either the coloniser or colonised. Often an external factor provided a context that might enable or hinder the process of decolonisation. Without doubt the most important external factor of decolonisation was the Second World War. The defeat and occupation of European colonial powers such as France and the Netherlands provided anti-colonial liberation movements with an opportunity in which both to assert their independence and fine-tune their political and military tactics, often against a new occupying power, Japan. The ultimate defeat of Japan created a power vacuum that well-established independence movements could fill and prove difficult to dislodge. Even though the most important imperial power Britain was not itself occupied during the war many of its colonies were. A second key external factor was economic. In an age of post-war austerity and international debt, Britain and other European powers often lacked the political resolve to maintain the economic burden of maintaining an empire in a Cold War age of changed priorities. Thirdly, there is little doubt that after 1945 a pro-independence/anti-colonial climate of international opinion developed that influenced even those colonies where little popular pre-war support for independence had been generated. By 1945 the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism, and delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and national activists.

|

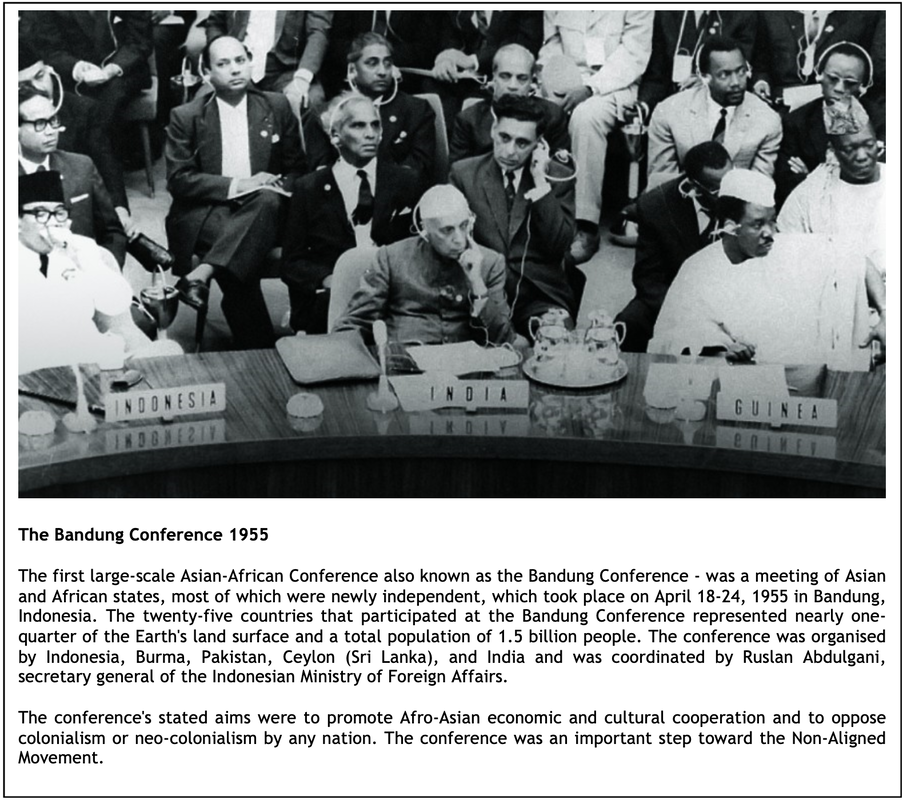

There was something of a domino effect as countries successfully asserted their independence and inspired others to follow them. A key moment in the international promotion of independence was the Bandung Conference in 1955. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan spoke of the rise of African national consciousness as a ‘wind of change’ blowing through the continent. Fourthly, the Cold War also provided an important anti-colonial momentum with both superpowers ideologically hostile to the traditional empire form of direct control, whilst they hypocritically promoted their own spheres of influence and proxy governance via compliant dictators. Unless there was a Cold War agenda for European powers to justify their colonial ambitions, they lacked the international support that was increasingly dominated by the policy priorities of the USA and USSR. The failed attempt by Britain and France to recapture the Suez Canal from Egyptian control in 1956 marked a significant external turning point in this regard. The Suez crisis provided a significant impetus to African decolonisation; forced to submit to the anti-colonial pressure of the Superpowers the European’s will to maintain their empires were subsequently deflated. Colonel Nasser emerged as the champion of the Arab cause and decolonisation.

|

Finally, the newly formed United Nations Organisation based on the anti-imperial principles of the 1941 Atlantic Charter, would prove to be both a powerful conduit and platform for national liberation movements. In response to point three of the Atlantic Charter’s stated principles that ‘all people had a right to self-determination’; the leader of the Indian independence movement Mohandas Gandhi wrote to President Roosevelt: ‘I venture to think that the Allied declaration that the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for the freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow so long as India and for that matter Africa are exploited by Great Britain...’

Internal Factors - help explain the nature of decolonisation.

An internal factor of decolonisation refers to something that encouraged or made possible the process of decolonisation that can be explained by events inside the colony or within the relationship between the colony and coloniser. The first important internal factor derives from the way in which the colony has historically been governed. When studying New Imperialism last year we identified three broad political types of imperialism:

1. Colonies (a) direct rule – where officials & soldiers are sent to administer colonies (typically French) (b) indirect rule – via sultans, chiefs, other local rulers - urged leaders to get education in home country to become westernized (typically British)

2. Protectorates - local rulers left in place but expected to follow advice of European advisers - cheaper than running a colony (e.g. Britain in Egypt)

3. Spheres of Influence - areas in which outside powers claimed exclusive investment or trading privileges (e.g. Europeans created them in China, U.S. in Latin America)

If the pre-liberation, colonial administration is direct and comprehensive, the more dependent the imperial periphery is on the imperial core. This will make a smooth transfer of power more difficult to achieve. If, however, an effective modern state infrastructure has been developed with the support and integration of a local elite, then the process of independence is likely to be easier because the local population have the wherewithal and experience to run a modern state. In addition, if the colonial power has encouraged a large number of settlers (often the case when good quality land and good climate) then this also makes decolonialisation more complicated. Nigeria had a larger population and more developed economy than Kenya at the time of decolonisation, which led to different political dynamics and paths to independence. In Kenya, the settler population controlled much of the country's fertile land, and their economic interests often conflicted with those of the indigenous population. In contrast, there were fewer European settlers in Nigeria, and they played a less prominent role in the decolonisation process.

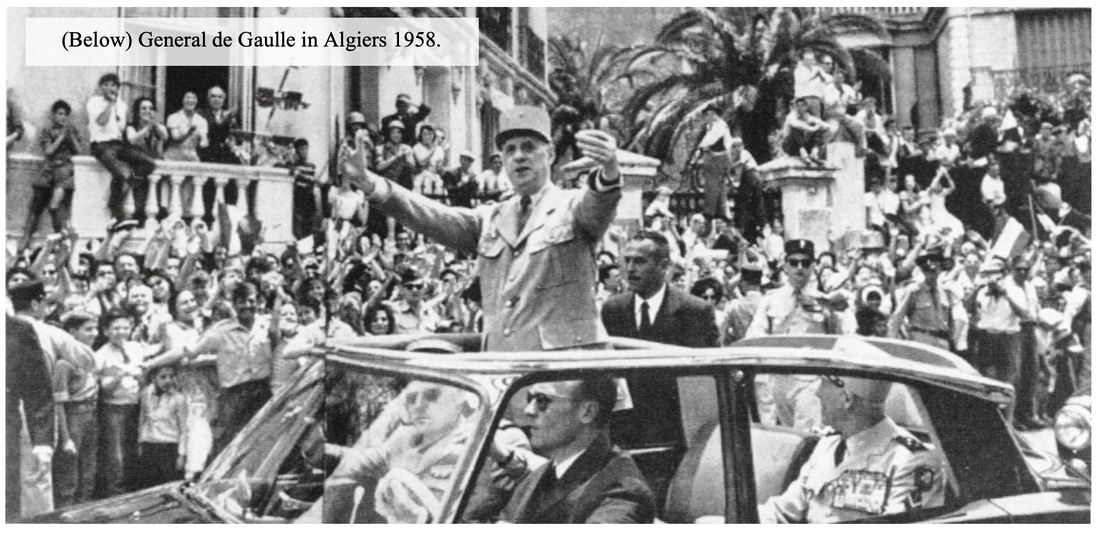

A second related internal factor is the attitude of the colonial power to the question of independence. There are many external reasons like war and economic difficulty which can put pressure on colonisers to relinquish control, but there can also be internal factors which can just as easily lead to a change in policy. An election outcome or a change in government personnel can result in an imperial government more willing to negotiate independence. Had Churchill been re-elected in Britain in 1945, the future independence of India may not have been achieved so early. In contrast, Charles de Gaulle’s belief that the rebuilding of France’s international prestige required her to hold on to her global empire at all costs resulted in a very different attitude to national independence movements in Paris.

An internal factor of decolonisation refers to something that encouraged or made possible the process of decolonisation that can be explained by events inside the colony or within the relationship between the colony and coloniser. The first important internal factor derives from the way in which the colony has historically been governed. When studying New Imperialism last year we identified three broad political types of imperialism:

1. Colonies (a) direct rule – where officials & soldiers are sent to administer colonies (typically French) (b) indirect rule – via sultans, chiefs, other local rulers - urged leaders to get education in home country to become westernized (typically British)

2. Protectorates - local rulers left in place but expected to follow advice of European advisers - cheaper than running a colony (e.g. Britain in Egypt)

3. Spheres of Influence - areas in which outside powers claimed exclusive investment or trading privileges (e.g. Europeans created them in China, U.S. in Latin America)

If the pre-liberation, colonial administration is direct and comprehensive, the more dependent the imperial periphery is on the imperial core. This will make a smooth transfer of power more difficult to achieve. If, however, an effective modern state infrastructure has been developed with the support and integration of a local elite, then the process of independence is likely to be easier because the local population have the wherewithal and experience to run a modern state. In addition, if the colonial power has encouraged a large number of settlers (often the case when good quality land and good climate) then this also makes decolonialisation more complicated. Nigeria had a larger population and more developed economy than Kenya at the time of decolonisation, which led to different political dynamics and paths to independence. In Kenya, the settler population controlled much of the country's fertile land, and their economic interests often conflicted with those of the indigenous population. In contrast, there were fewer European settlers in Nigeria, and they played a less prominent role in the decolonisation process.

A second related internal factor is the attitude of the colonial power to the question of independence. There are many external reasons like war and economic difficulty which can put pressure on colonisers to relinquish control, but there can also be internal factors which can just as easily lead to a change in policy. An election outcome or a change in government personnel can result in an imperial government more willing to negotiate independence. Had Churchill been re-elected in Britain in 1945, the future independence of India may not have been achieved so early. In contrast, Charles de Gaulle’s belief that the rebuilding of France’s international prestige required her to hold on to her global empire at all costs resulted in a very different attitude to national independence movements in Paris.

|

A third key internal factor is the level of socio-economic development of the colonies themselves. As with any revolution, an effective organisation of revolutionary change depends, to some extent, or an ability to mobilise people against the status quo. Higher levels of literacy and civic (national) culture, the existence of mass-media and popular pressure groups are all indicators that a genuinely popular movement might be created. For example, the existence of western style education promoted decolonisation as it helps the young in subject countries assimilate revolutionary enlightenment concepts such as freedom and equality.

|

A final key internal factor was the very existence of an organised popular movement or political party, dedicated to the goal of independence itself. Organisations such as the Congress Party in India, Convention People's Party in Ghana or the FLN (National Liberation Front) in Algeria, campaigned - often illegally - for the creation of a state independent of colonial influence.

|

Activity

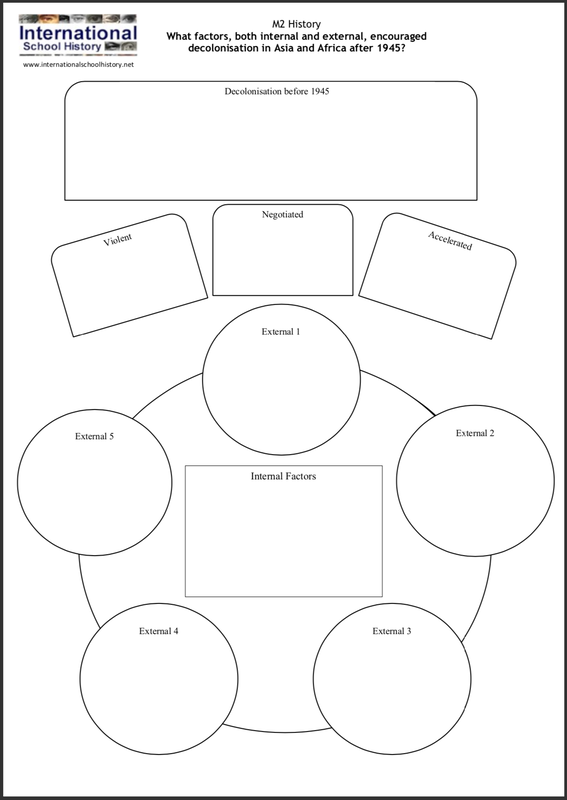

Make a copy (by hand or with a computer) of the diagram 'What factors, both internal and external, encouraged decolonisation in Asia and Africa after 1945?' and complete it with the information contained in this chapter.

Above is the presentation from the lesson which is a summary of the information contained in this section. |

Extension and extra-reading.

Useful for IB students in particular who chose to prepare for the essays in Paper 2, Topic 8 Independence Movements, is the work of two historians who had a profound impact on me as a student. Eric Hobsbawm's 'history of the short 20th century' came out when I was a student and this is the chapter on decolonisation. Clive Ponting taught me at Swansea and this chapter on decolonisation is part of his ambitious pioneering 'big history' of the 20th century.

Useful for IB students in particular who chose to prepare for the essays in Paper 2, Topic 8 Independence Movements, is the work of two historians who had a profound impact on me as a student. Eric Hobsbawm's 'history of the short 20th century' came out when I was a student and this is the chapter on decolonisation. Clive Ponting taught me at Swansea and this chapter on decolonisation is part of his ambitious pioneering 'big history' of the 20th century.

On the impact of the Suez Crisis (1956) see this BBC documentary below.

|

|