Lesson 8 - Switzerland

This is the last lesson on the Industrial Revolution, which means in addition to completing the activities for this topic you also need to revise for the end of unit test which will take place next lesson.

|

Why was Switzerland one of the first countries to industrialise?

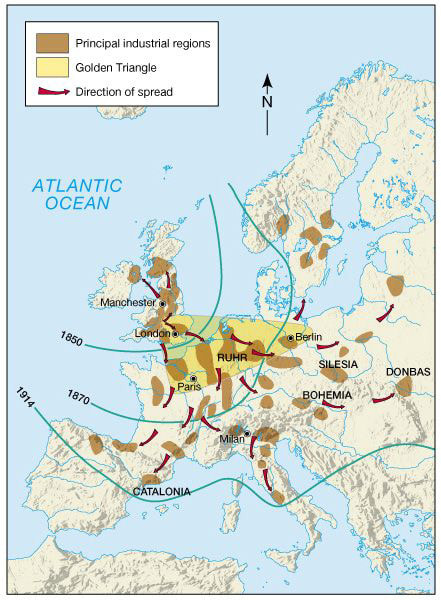

The industrial revolution began in the 1760s in Britain, then spread to the rest of Europe, first affecting northern France and Belgium, Switzerland, around 1800-1820. On the surface, there seem to be no obvious reasons why Switzerland should have been early to industrialise. Unlike the other countries, Switzerland has no obvious natural advantages. Mountainous and cut off from the sea, Switzerland does not have easy access to coal and iron reserves. But Switzerland does have a geographically central location close to markets and other industrial centres, access to the Rhine, rivers to power factories and a culture of political liberalism, socio-cultural freedom and the Protestant tradition which had been important to the early development of capitalism in the Netherlands and Britain. Towns like Geneva and Basel had long been renowned for their political and intellectual freedom, centres of learning and enlightened thinking. In Switzerland, feudal restriction had been lifted to allow free movement of labour and self-governing urban centres existed with merchant capitalists ready to invest their money in new enterprises and technology. And perhaps most importantly, Switzerland was already an advanced European centre for the industry that kickstarted the Industrial Revolution: textiles. |

Textile industry

Eastern Switzerland had been an important centre for textile (cloth) production since the end of the middle ages. In St. Gallen the ‘domestic system’ had been introduced in the 15th century. There was already a sophisticated division of labour with the ‘putting-out system’ where the work of skilled handloom weavers was supplied and distributed by a merchant capitalist class.

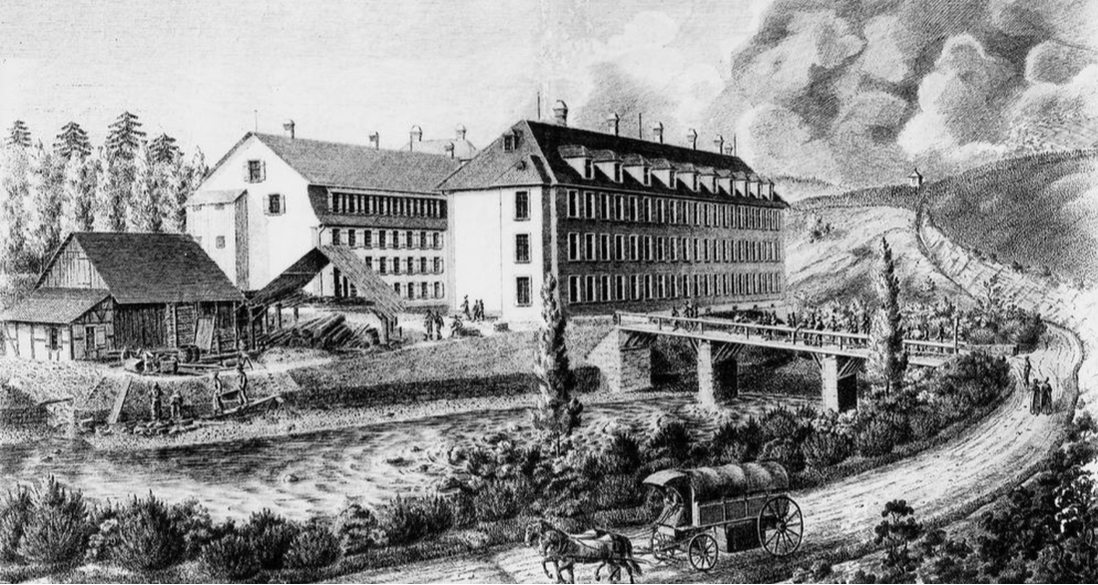

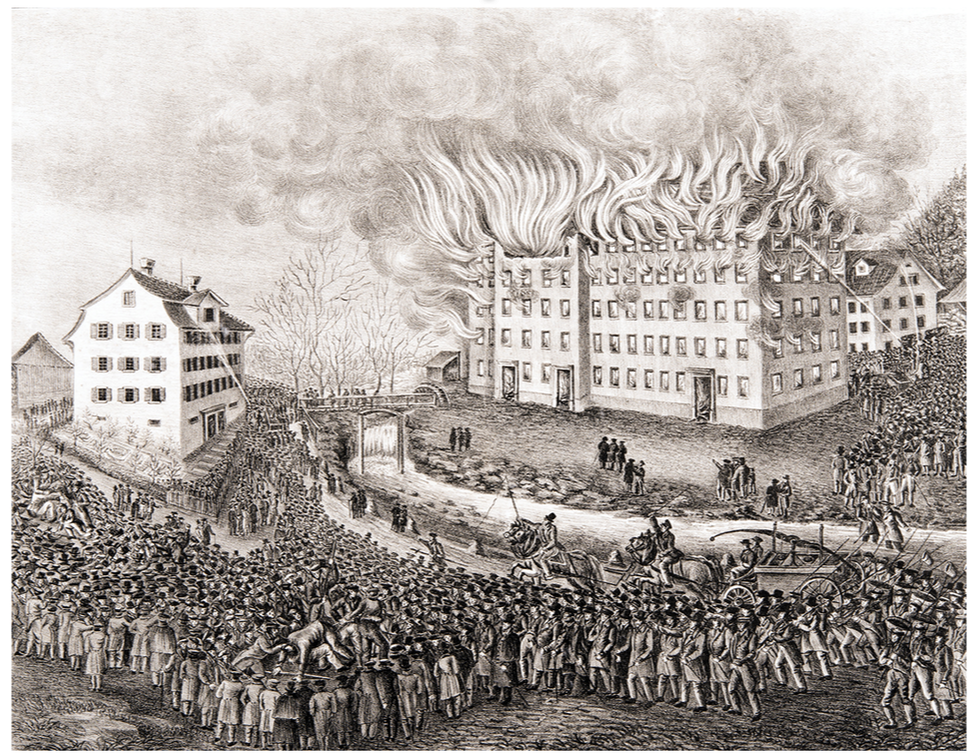

The production by machines in Switzerland began in 1801 in St. Gallen with the import of the latest machines from Great Britain. In Switzerland, hydraulic power was used instead of steam-engines because in the mountains and hills there is relatively easy access to waterpower. As early as 1814 the machines had replaced textile production by hand completely. (Below one of the biggest spinning factories, La filature du Hard at Winterthour in about 1820).

Eastern Switzerland had been an important centre for textile (cloth) production since the end of the middle ages. In St. Gallen the ‘domestic system’ had been introduced in the 15th century. There was already a sophisticated division of labour with the ‘putting-out system’ where the work of skilled handloom weavers was supplied and distributed by a merchant capitalist class.

The production by machines in Switzerland began in 1801 in St. Gallen with the import of the latest machines from Great Britain. In Switzerland, hydraulic power was used instead of steam-engines because in the mountains and hills there is relatively easy access to waterpower. As early as 1814 the machines had replaced textile production by hand completely. (Below one of the biggest spinning factories, La filature du Hard at Winterthour in about 1820).

Mechanical Engineering

A second area of industrial innovation came with the development of machine manufacture. As we saw in a previous unit, France’s Continental Blockade attempted to isolate Britain from European trade during the Napoleonic Wars. In Switzerland, this meant that British industrial machinery could not be imported. This provided the incentive for Swiss textile manufactures to begin producing their own machines. 1805 Escher, Wyss & Co. (Zurich) and 1810 Johann Jacob Rieter & Co. (Winterthur) were amongst the first engineering companies to establish what became a rich industrial tradition in the north-east of Switzerland.

A second area of industrial innovation came with the development of machine manufacture. As we saw in a previous unit, France’s Continental Blockade attempted to isolate Britain from European trade during the Napoleonic Wars. In Switzerland, this meant that British industrial machinery could not be imported. This provided the incentive for Swiss textile manufactures to begin producing their own machines. 1805 Escher, Wyss & Co. (Zurich) and 1810 Johann Jacob Rieter & Co. (Winterthur) were amongst the first engineering companies to establish what became a rich industrial tradition in the north-east of Switzerland.

|

|

Watchmaking as an 'adjacent possible'.

The industry most associated with Switzerland is watchmaking and as with textiles, its origins are to be found in history that predates the industrial revolution. It was the freedom and religious toleration of Geneva that encouraged French Protestant (Huguenots) watchmakers to settle there in the 16th century. By the late 18th century, watch making had spread north to Neuchâtel. Around 1785 some 20,000 people worked in the watchmaking industry of Geneva and produced 85,000 watches per year, another 50,000 watches were produced in the region of Neuchâtel. As the Mark Williams film opposite explains there are clear links between the skillls and technology needed to produce clocks and those needed to produce industrial machines. |

Just as Galileo developed a telescope by using eye glasses that had been developed to help people read, because people now needed to read because of Guttenburg's printing press, so the early industrialists used the ideas of cogs and wheels from the clock industry in the development of their new machines. The writer Steven Johnson talks about the concept of 'adjacent possible' in the respect. Johnson emphasizes the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate events and trends. The adjacent possible is the area you can readily explore and reach with small, incremental steps. It's not about leaping to distant, unimaginable futures, but about the next logical steps based on what already exists.

Chemical and food industries

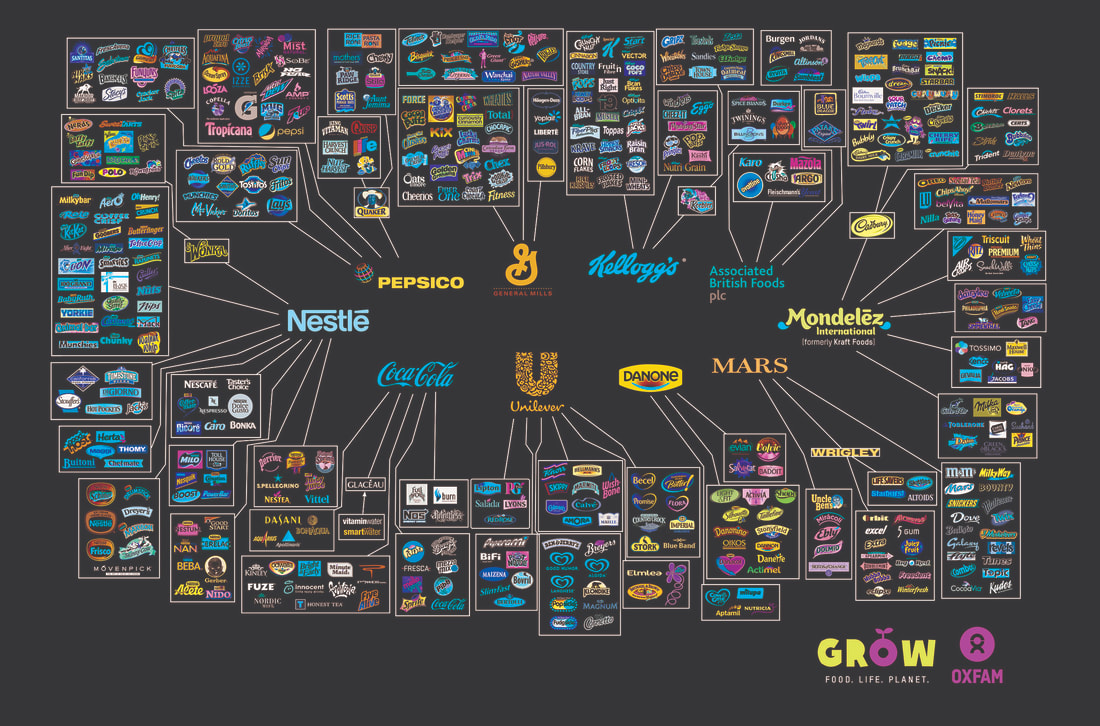

The first chemical factory in Switzerland was founded by Daniel Frey at Aarau in 1804. The industry started to become important from the 1850s. In 1859 Alexandre Clavel, Louis Durand and Etienne Marnas came from France to Basel to produce synthetic colors. From 1884 their company was known as Chemische Industrie Basel (CIBA). Basel is still today a world centre for the chemical and pharmaceutical industry. The first cheese factory in Europe was built in Switzerland in 1815 and Swiss immigrants also established the first factories in the USA. Chocolate was produced in Switzerland as early as 1803 by hand-crafted methods. In 1819 François-Louis Cailler founded his chocolate factory at Vevey. Advertising by Philippe Suchard (Neuchâtel 1826) made Swiss Chocolate known to the world. Daniel Peter (from Vevey) invented milk chocolate in 1875 and Rodolphe Lindt developed a new method to make chocolate melt on the tongue (not a sandy texture) in 1879.

The first chemical factory in Switzerland was founded by Daniel Frey at Aarau in 1804. The industry started to become important from the 1850s. In 1859 Alexandre Clavel, Louis Durand and Etienne Marnas came from France to Basel to produce synthetic colors. From 1884 their company was known as Chemische Industrie Basel (CIBA). Basel is still today a world centre for the chemical and pharmaceutical industry. The first cheese factory in Europe was built in Switzerland in 1815 and Swiss immigrants also established the first factories in the USA. Chocolate was produced in Switzerland as early as 1803 by hand-crafted methods. In 1819 François-Louis Cailler founded his chocolate factory at Vevey. Advertising by Philippe Suchard (Neuchâtel 1826) made Swiss Chocolate known to the world. Daniel Peter (from Vevey) invented milk chocolate in 1875 and Rodolphe Lindt developed a new method to make chocolate melt on the tongue (not a sandy texture) in 1879.

|

The Swiss invention of ready meals.

Industrialisation created a market for products that could be prepared and eaten quickly, sometimes even during work at the factories. Maggi and Knorr were Swiss companies that created instant soups in cubes or bags. Condensed milk was one of the first products to be industrially produced by the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Co and Nestlé; the two companies merged in 1905. In 1865 the company Wander in Bern invented Ovomaltine. Henri Nestlé invented a food for babies based on milk, sweeteners and flour in 1866. His factory at Vevey became in 1905 became one of the first multinational food industries. For more on the history of the Swiss food industry see this recent blog from the Swiss National Museum. |

Railways

The development of the railways in Switzerland was relatively late. In the 1840s, individual cantons still imposed tariffs and tolls on people and goods that crossed their frontiers. The new federal constitution of 1848 enabled the planning and financing of railways and soon after there was rapid expansion with more than 1000km of line built in a 10-year period. By the time the federal government took over (nationalised) the railways in 1898, Switzerland had one of the densest railway networks in the world.

|

Socio-economic consequences

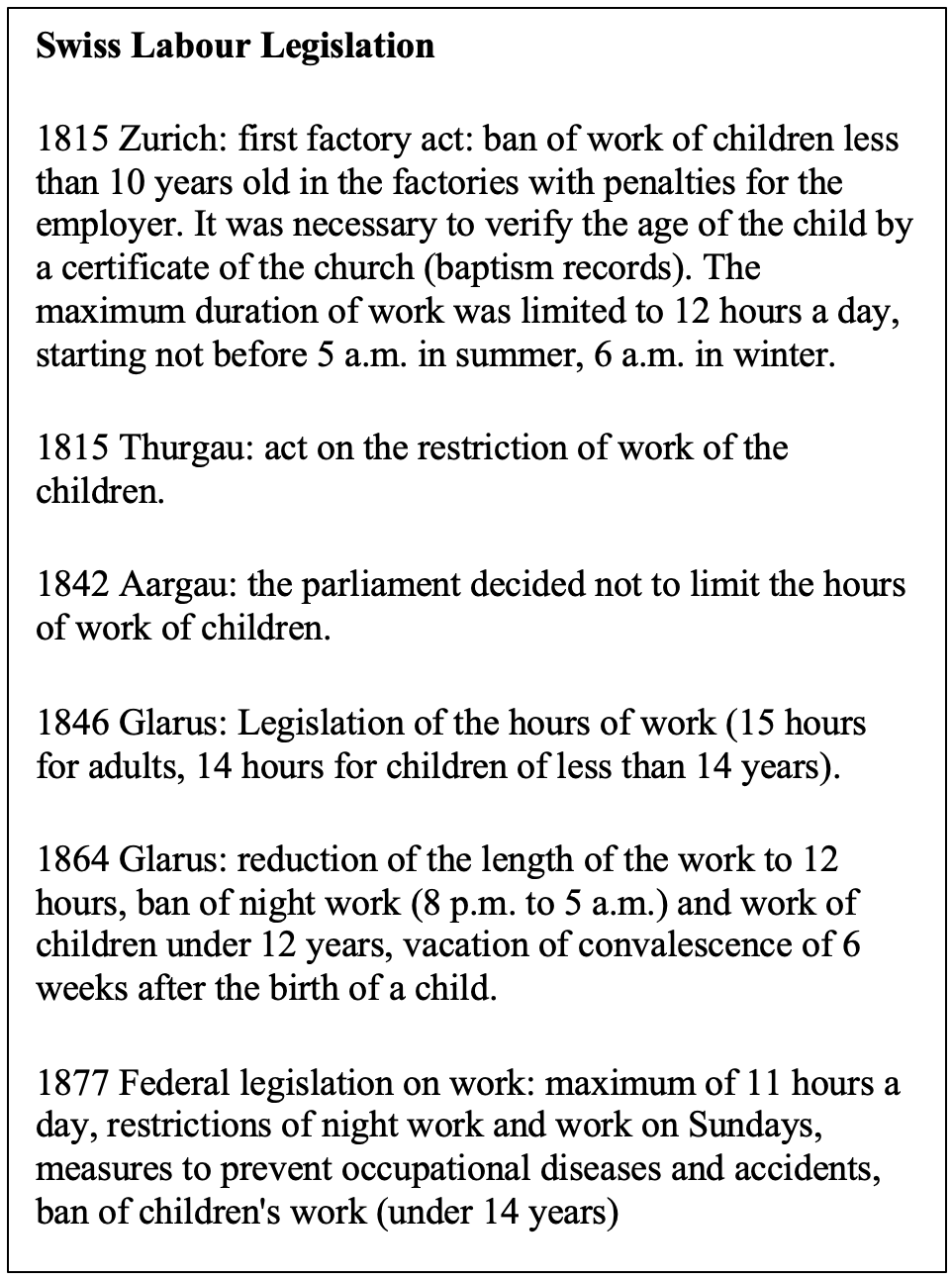

The absence of raw materials meant that Swiss industry did not concentrate in coal basins. There were no big industrial cities as Swiss industries tended to disperse along rivers supplying waterpower (ribbon development). Low wages and a less protected workforce helped Swiss manufacture to continue to compete effectively with the technologically advanced industry of Britain. For a long time, Swiss workers remained much less paid than in England and laws to protect workers were slower to be enacted. (See table opposite) But the living conditions for workers were relatively better, and prices and rents in Switzerland were still much lower than in England. Poor wages and child labour were two of the common features of the Swiss industrial revolution. It wasn’t until 1877 that federal laws were implemented to outlaw the employment of children (under 14 years of age.) As in Britain, employers were under no obligation to provide healthy housing or safe working conditions. On average, a factory worker had a life expectancy of 35 years, while wealthier citizens could live up to 55 years. The response of the working class |

The development of trade unions and political parties was a gradual process and as in Britain it was opposed by employers who feared a loss of their competitivity. Also, as in Britain, the first responses of the working classes to the industrial revolution could be violent and targeted the machinery that threatened their jobs. The most famous incident took place in Uster, near Zurich in 1832. (See image below) As in the north of industrial England, qualified handloom weavers saw their newly installed machinery forcing down the level of their wages. The coordinated attack on the Corrodi & Pfister spinning mill resulted in the destruction of the factory, 75 arrests and sentences of up to 24 years in prison with hard labour for the organisers.

Although the first trade unions appeared as early in 1838, it was not until the 1870s with the foundation of l'Union syndicale suisse (USS) that real improvements in the conditions of work were achieved. The 1877 Factory Act restricted the length of the working day throughout Switzerland and safety measures were compulsorily introduced in the most dangerous industries. Workers wages increased four-fold in the second half of the 19th century, although health insurance to cover accidents at work was not introduced until 1912 and even then, it was not compulsory.

Perhaps the key development in the history of the Swiss working class was the foundation of the Social Democratic Party on 21 October 1888. The SP was a socialist party committed to winning political power as a means of improving the lives of workers. But as in Britain, it wasn’t until after the first world war that the SP became a serious political force.

Perhaps the key development in the history of the Swiss working class was the foundation of the Social Democratic Party on 21 October 1888. The SP was a socialist party committed to winning political power as a means of improving the lives of workers. But as in Britain, it wasn’t until after the first world war that the SP became a serious political force.

Activities

- Explain why despite lacking natural advantages, Switzerland was one of the first countries in the world to industrialise.

- Draw a revision diagram/table of the main industries of the Swiss industrial revolution.

- Compare and contrast the impact of the industrial revolution in Switzerland with that of Britain. What were the main similarities and differences? (Consider using a PESC approach. This is designed to be a revision activity and opportunity to review your work on the UK.)