Lesson 2 - Introduction - The long-term causes of WW1: Imperialism, Nationalism and Militarism.

But first a word of warning...

The main problem with 'big events' in history is that they seem to need big explanations. Surely, something as catastrophic as the First World War can not have happened easily? And yet in 1914 and despite the best efforts of Europe's statesmen, war seemed almost inevitable and certainly impossible to stop. This apparent powerlessness in 1914, helps to explain why historians have sought to explain the war by looking beyond human 'agency' (the actions of individuals) to look at those 'vast impersonal forces' (T.S. Eliot) such as imperialism, militarism and nationalism which seemed to drive an unwitting humanity over the edge. The one major advantage of this historical approach is that it suggests no-one was to blame for the First World War and the 20m+ deaths that resulted. We'll return to this question of human agency and blame later.

The main problem with 'big events' in history is that they seem to need big explanations. Surely, something as catastrophic as the First World War can not have happened easily? And yet in 1914 and despite the best efforts of Europe's statesmen, war seemed almost inevitable and certainly impossible to stop. This apparent powerlessness in 1914, helps to explain why historians have sought to explain the war by looking beyond human 'agency' (the actions of individuals) to look at those 'vast impersonal forces' (T.S. Eliot) such as imperialism, militarism and nationalism which seemed to drive an unwitting humanity over the edge. The one major advantage of this historical approach is that it suggests no-one was to blame for the First World War and the 20m+ deaths that resulted. We'll return to this question of human agency and blame later.

Imperialism

As you will remember, until 1850, the European exploration and subsequent exploitation of Africa had largely been limited to the coastal areas. By the 1870s, however, entrepreneurial explorers such as Henry Stanley had begun to awaken to the economic potential of the African interior, touching off a race by European states to claim their own colonies in Africa. The potential of this "scramble" to bring far-flung powers into conflict should be obvious. It certainly was to Bismarck. Despite his disdain for overseas colonies, Bismarck hosted a conference in Berlin in 1885 to hammer out the rules for claiming and exploiting Africa in hopes that these rules would prevent disagreements over ownership. Just as he had no interest in Germany acquiring her own colonies, he did not want disputes between other powers in some distant African land to jeopardise his new Germany by dragging her into a European war

As you will remember, until 1850, the European exploration and subsequent exploitation of Africa had largely been limited to the coastal areas. By the 1870s, however, entrepreneurial explorers such as Henry Stanley had begun to awaken to the economic potential of the African interior, touching off a race by European states to claim their own colonies in Africa. The potential of this "scramble" to bring far-flung powers into conflict should be obvious. It certainly was to Bismarck. Despite his disdain for overseas colonies, Bismarck hosted a conference in Berlin in 1885 to hammer out the rules for claiming and exploiting Africa in hopes that these rules would prevent disagreements over ownership. Just as he had no interest in Germany acquiring her own colonies, he did not want disputes between other powers in some distant African land to jeopardise his new Germany by dragging her into a European war

But in order to feed their massive industrial and military machines, the powers needed access to resources. This need had been momentarily satisfied by the 'scramble for Africa', but by 1900 the demand had returned. The European powers had claimed all of Africa, with a few small exceptions. Sources of raw materials, not to mention markets, had to be taken forcibly or diplomatically, from another power.

Despite Bismarck’s efforts, and in some ways because of his efforts, the European powers would come dangerously close to war over African questions after Bismarck's 'retirement' in 1890. Young Wilhelm demanded that Germany get her "place in the sun" and developed a brash, provocative and ultimately dangerous Weltpolitik (world policy) to achieve it.

Nationalism

As we saw earlier this year, nationalism was powerful by-product of the process of industrialisation in all modernising states. National railway networks, education systems and media began to create a powerful sense of imagined identities that allowed the people of a state to distinguish themselves from neighbouring states. This was particularly important in groups of national people who were subject to the rule of an empire that denied them the right to express that identity.

The role that nationalism played in the growing international tensions at the turn of the century is best demonstrated in the Balkans. This region was populated by a number of ethnic groups broadly referred to as Slavs and centred in the small independent nation-state of Serbia. Political domination in the region had traditionally been split between two rival empires, the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman. By the end of the 19th century, the crumbling influence and power of the Ottoman Empire, coupled with Austria-Hungary's desire expand her influence in the region, made this a very unstable part of the European political system. As we have seen, Russia also had an interest. Growing numbers of radical pan-Slavic nationalists living under the Hapsburgs were convinced that their future lay not in a federated Austria-Hungary, but rather in a Greater Serbia or Yugoslavia. With Serbia's ambition to become the Piedmont of a pan-Slavic state added to this frightening situation, the region was becoming dangerously volatile.

Militarism

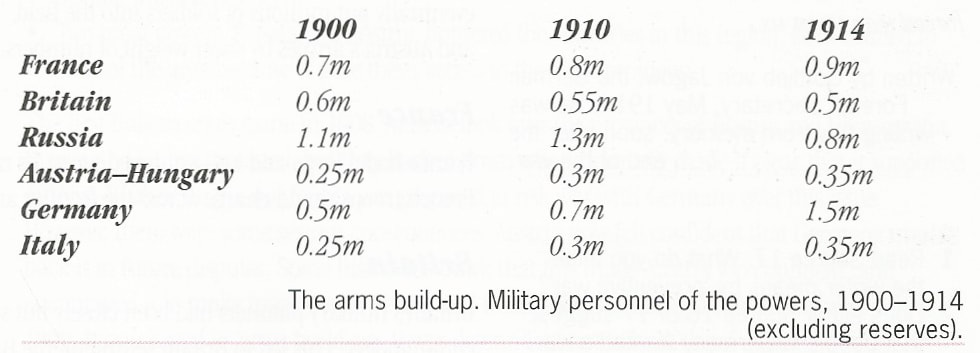

Broadly speaking, we can talk about militarism as an overall societal emphasis on the military. The trend towards massive armies and navies at the end of the 19th century can be highlighted in two ways. On the one hand there are the precise, technical aspects that appeal to many military historians—warship tonnage, troop concentration, military expenditure. On the other hand, we should consider those aspects that appeal to the social historian—the relation of the military to the wider society. The size of an army or a navy became a source of enormous national pride. It is certainly true that at the turn of the last century, the militaries of the major European powers were the largest in history. The idea of war was glorified and normalised. The alliances of great powers made it clear to the public who the enemy was and why they should be afraid. Paradoxically, most statesmen, if not generals, believed that this could help avoid a war. This early idea of deterrence held that the larger a country's military, the less likely other countries would be to attack. This might have been true if the size of militaries had remained static. The big problem was that they were growing. If a country was worried that a rival state's army was growing faster than its own, the temptation was to attack the rival pre-emptively before the differential was too great. In short, use your army before you lost it. This was to have ominous ramifications in July 1914.

Despite Bismarck’s efforts, and in some ways because of his efforts, the European powers would come dangerously close to war over African questions after Bismarck's 'retirement' in 1890. Young Wilhelm demanded that Germany get her "place in the sun" and developed a brash, provocative and ultimately dangerous Weltpolitik (world policy) to achieve it.

Nationalism

As we saw earlier this year, nationalism was powerful by-product of the process of industrialisation in all modernising states. National railway networks, education systems and media began to create a powerful sense of imagined identities that allowed the people of a state to distinguish themselves from neighbouring states. This was particularly important in groups of national people who were subject to the rule of an empire that denied them the right to express that identity.

The role that nationalism played in the growing international tensions at the turn of the century is best demonstrated in the Balkans. This region was populated by a number of ethnic groups broadly referred to as Slavs and centred in the small independent nation-state of Serbia. Political domination in the region had traditionally been split between two rival empires, the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman. By the end of the 19th century, the crumbling influence and power of the Ottoman Empire, coupled with Austria-Hungary's desire expand her influence in the region, made this a very unstable part of the European political system. As we have seen, Russia also had an interest. Growing numbers of radical pan-Slavic nationalists living under the Hapsburgs were convinced that their future lay not in a federated Austria-Hungary, but rather in a Greater Serbia or Yugoslavia. With Serbia's ambition to become the Piedmont of a pan-Slavic state added to this frightening situation, the region was becoming dangerously volatile.

Militarism

Broadly speaking, we can talk about militarism as an overall societal emphasis on the military. The trend towards massive armies and navies at the end of the 19th century can be highlighted in two ways. On the one hand there are the precise, technical aspects that appeal to many military historians—warship tonnage, troop concentration, military expenditure. On the other hand, we should consider those aspects that appeal to the social historian—the relation of the military to the wider society. The size of an army or a navy became a source of enormous national pride. It is certainly true that at the turn of the last century, the militaries of the major European powers were the largest in history. The idea of war was glorified and normalised. The alliances of great powers made it clear to the public who the enemy was and why they should be afraid. Paradoxically, most statesmen, if not generals, believed that this could help avoid a war. This early idea of deterrence held that the larger a country's military, the less likely other countries would be to attack. This might have been true if the size of militaries had remained static. The big problem was that they were growing. If a country was worried that a rival state's army was growing faster than its own, the temptation was to attack the rival pre-emptively before the differential was too great. In short, use your army before you lost it. This was to have ominous ramifications in July 1914.

The above is an edited extract from IB Course Companion: 20th Century World History,

Cannon, Jones-Nerzic, Keys, Mamaux, Miller, Pope, Smith and Williams.

Cannon, Jones-Nerzic, Keys, Mamaux, Miller, Pope, Smith and Williams.

|

Activity 1

Download a copy of the sheet, 'Imperialism, Nationalism and Militarism'. In each of the boxes explain what is meant by the key term and how it might contribute to tensions which might cause war. |

1900-1914 - Examples of imperialism, nationalism and militarism.

|

|

As we move closer to 1914 we study a series of events each of which helped contribute to the hostile climate that made war more likely in 1914. But the danger is that when we look closely at singular events we lose sight of the bigger picture.

In this activity I am going to describe - chronologically - the unfolding of events that led to 1914. Your job will be to extract them from their chronological moment in time and fit them in as further examples of imperialism, nationalism and militarism. See textbook pages 8-11 |

|

One of the most significant causes of tension in Europe was the naval rivalry which developed after 1900. As we saw last year, since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Britain had ruled the seas without any challenge. Its navy was the most powerful in the world. This situation began to change in 1898 when the new Kaiser, Wilhelm, announced his intention to build a powerful German navy. Britain felt very threatened by this. Germany’s navy was much smaller than Britain’s but the British navy was spread all over the world, protecting the British Empire. The Kaiser and his admirals felt that Germany needed a navy to protect its growing trade. In 1906 Britain raised the stakes in the naval race by launching HMS Dreadnought (right), the first of a new class of warships. Germany responded by building its own ‘Dreadnoughts’. Both Britain and Germany spent millions on their new ships and the public, fortified by popular nationalism, encouraged them to do so.

|

|

|

Partly as a result of this rivalry, Britain concluded agreements with its two major colonial rivals: the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907. The First Moroccan Crisis (Tangier Crisis) was an international dispute between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. In 1905 the Kaiser visited Morocco. As we have seen, Germany was building up its own African empire and had colonies in central and southern Africa . The Kaiser was now keen to show that Germany was an important power in North Africa as well. The French had plans to take control of Morocco so the Kaiser made a speech saying he supported independence for Morocco. The French were furious at his interfering in their affairs. An international conference was held in Algeciras in 1906.

|

But the conference did not cool things down. At the conference the Kaiser was humiliated. He had wanted to be seen as a major power in Africa. Instead his views were rejected. The crisis worsened German relations with both France and the United Kingdom, and helped ensure the success of the new Anglo-French Entente Cordiale. Kaiser Wilhelm II was angry at being humiliated and was determined not to back down again, which led to the German involvement in the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911. (Agadir Crisis). Germany's decision to send a gunboat to Agadir almost led to war. Heightened concerns in the UK about the strength of the German navy led to an increase in British naval spending and closer cooperation with France. The two nations concluded a secret naval agreement. This agreement involved the UK taking responsibility for protecting the French coast from German attack, while France focused on guarding the Mediterranean and British interests there. The British cabinet was not informed of this agreement until August 1914 when they were asked to defend France from Germany.

The Morrocan Crises explained in three 'Punch' cartoons (popular with examiners).

Can you explain the meaning of the cartoons with reference to the historical context that produced them?

|

As tensions worsened, all countries looked to their military capability and began to plan for future conflict. The size of armies, the length of military service and level of investment all increased. Public support for militarism was encouraged by newspapers and popular nationalism reached new levels of enthusiasm. In Germany, in particular, war and militarism were glorified. The Kaiser surrounded himself with military advisers. He staged military rallies and processions. He loved to be photographed in military uniforms.

|

The arms race in which all the major powers were involved contributed to the sense that war was bound to come, and soon. Financing it caused serious financial difficulties for all the governments involved in the race; and yet they were convinced there was no way of stopping it.

Although publicly the arms race was justified to prevent war, no government had in fact been deterred from arming by the programmes of their rivals, but rather increased the pace of their own armament production.

James Joll, Origins of the First World War, 1992.

|

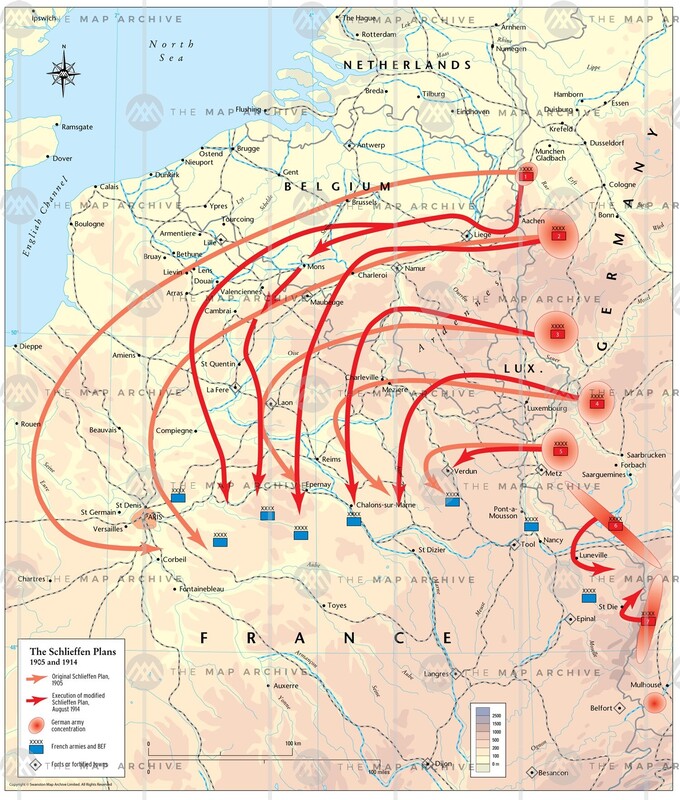

Many countries felt so sure that war was ‘bound to come’ sooner or later that they began to make very detailed plans for what to do if and when it did. Within the general staff of each country, complex plans for future war were developed that tried to learn the lessons from the Franco-Prussian war. Countries adapted to the Prussian model (See von Moltke reforms Matu 5 and Japanese military reforms Matu 6) and the importance mobilising troops as quickly as possible.

The problem facing the German commanders was that if a war broke out they would probably have to fight against Russia and France at the same time. In 1905, the Germans came up with the Schlieffen Plan. Under this plan they would quickly attack and defeat France, then turn their forces on Russia which were expected to be slow to get its troops ready for war. Austria-Hungary knew it needed the help of Germany to hold back Russia. It too relied on the success of the Schlieffen Plan so that Germany could help it to defeat Russia. The Russian army was badly equipped, but it was huge. The Russian plan was to overwhelm Germany’s and Austria’s armies by sheer weight of numbers. France had a large and well-equipped army. Its main plan of attack was known as Plan 17. French troops would charge across the frontier and attack deep into Germany, forcing surrender. Since the Moroccan crises Britain’s military planners had been closely but secretly involved in collaboration with French commanders. It also meant that Britain had a more of a moral obligation to support France if she was attacked. |

One thing that unites all of these plans was the assumption that a war, if and when it came, would be quick. These military plans were designed to achieve a quick victory. No one planned for what to do if the war dragged on.

|

The next crisis came in the Balkans in 1908. As we have seen previously the area had been ruled by Turkey, but Turkish power had been in decline throughout the 19th century. (See Crimean War 1853-56 - Matu 5 and Serbian independance 1878 - Matu 12) She was known as the 'sick man of Europe'. The new governments which had been set up in place of Turkish rule were regularly in dispute with each other. Two great powers, Russia and Austria, bordered the countries in this region.

|

However, there were some serious consequences. Austria now felt confident that Germany would back it in future disputes. Some historians think that this made Austria too confident, and encouraged it to make trouble with Serbia and Russia. Russia resented being forced to back down in 1909. It quickened its arms build-up. It was determined not to let it happen again.

From 1912 to 1913 there was a series of Balkan Wars. Serbia emerged from these as the most powerful country in the Balkans. Serbia emerged from these as the most powerful country in the Balkans. Slavic nationalists in the Habsburg (Austrian) empire wanted independence and looked to Serbia for inspiration and help. This was very serious for Austria. Serbia had a strong army and it was a close ally of Russia. Austria decided that Serbia would have to be dealt with. By this time, Russia had mostly recovered from its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, and the calculations of Germany and Austria were driven by a fear that Russia would eventually become too strong to be challenged. Their conclusion was that any war with Russia had to occur within the next few years in order to have any chance of success. In 1914 Austria was looking for a good excuse to crush Serbia. Austria’s opportunity came with the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo .

|

Activity 2

Make a copy of the narrative above '1900-1914' by downloading the 800 word text here. As you read through the text, highlight (in three different colours) examples of causes as imperialist, militarist and nationalist. Add a selection of these examples to the table you completed in Activity 1. The film (right) takes the causation narrative back into the 19th century with the Italian and German wars of unification. The first three minutes or so provide you with a good overview of the geo-political issues at stake.

|

|