Matu syllabus reference - Révolution française : définir la notion de révolution, des aspirations et ses acteurs, notamment à travers la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme et du citoyen ; mettre en évidence les nouvelles formes d’organisation politiques, opposées à la monarchie absolue et inspirées du Siècle des Lumières; Matu syllabus

Revision

|

A4 Revision essentials is a printable but not editable A4 sheet with the absolute essentials to hopefully help you pass the Matu.

'Six like Sydney' is from the notes of a very successful former student. These are often more detailed than the website and might be edited to create your own notes. |

Matu 2 - End of Unit Test

There will be three sections to this test.

Section A - Factual recall - This will require one-word answers to a set of factual questions. All the questions will be taken from this quiz.

There will be three sections to this test.

Section A - Factual recall - This will require one-word answers to a set of factual questions. All the questions will be taken from this quiz.

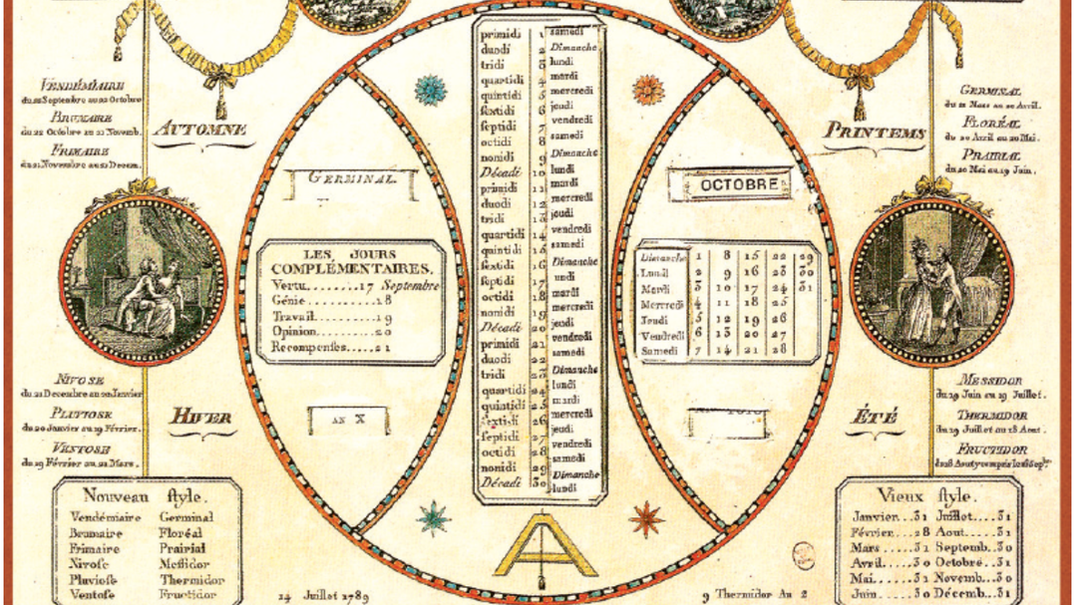

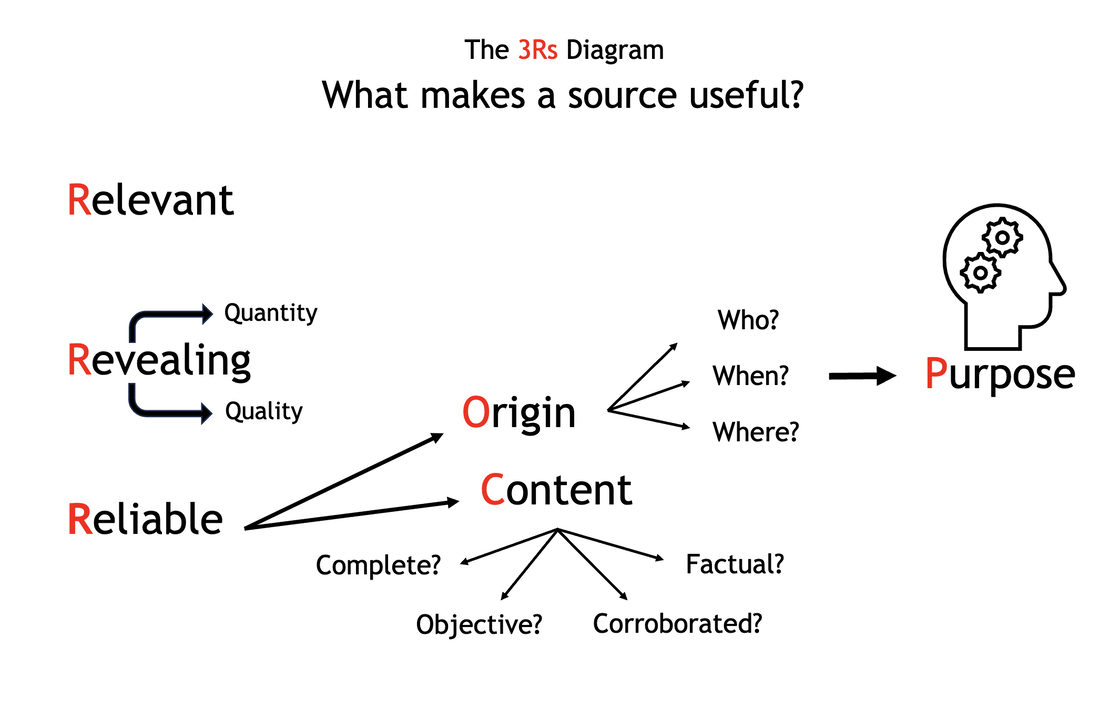

Section B - Source analysis - You will asked to analyse a series of sources to reflect on the extent to which they agree with each other or the extent to which they help answer a historical question. The concept of the utility of historical sources is useful in this respect. Pay particular attention to Lesson 5.

Section C - Explanatory questions - You will be expected to answer two from the following list of questions. The best answers will try to make a series of Points that are explained with examples:

- What were the long-term causes of the revolution?

- What were the short-term causes of the revolution?

- How did the king lose power between 1789-91?

- Why did France become a republic and execute the king?

|

|

|