Lesson 7c - How did Stalin gain support from policies and what did he aim to achieve?

The last two lessons on the rise to power and consolidation of power of Stalin have concentrated on the the use of formal and informal social control (coercion and persuation). This lesson shifts the focus to look at the things Stalin did that were designed to win the support of the Soviet people, that is to earn their consent. In realty though coercion, persuasion and consent are present at all times in the relationship between the state and the individual. The first film below should remind you of the coercion, persuasion and consent model. The other two films try to explain the two different forms of consent that operate: explicit and implicit. As we will see later, the more totalitarian a state is, the more important is the expected level of explicit consent.

|

|

|

|

Stalin provides us with a significantly different case study in totalitarianism when compared to the fascist examples of Mussolini and Hitler. Most importantly, the ideological differences of Communism had a significant impact on the aim and policies of the regime and the extent to which the state was able to control the lives of the individual.

In brief, the Communist state abolished capitalism and replaced the free market with a command economy in which the state took on the responsibility for the production and distribution of resources. This not only increased the power of the state, it also created a massive bureaucracy in which Communist Party members exercised considerable power. This new class of 'nomenklatura' provided the regime with the basis of its popular consent, controlling the new hierarchical 'prerogative state' in which the chairmanship of the party became the most important position of power in the country.

In brief, the Communist state abolished capitalism and replaced the free market with a command economy in which the state took on the responsibility for the production and distribution of resources. This not only increased the power of the state, it also created a massive bureaucracy in which Communist Party members exercised considerable power. This new class of 'nomenklatura' provided the regime with the basis of its popular consent, controlling the new hierarchical 'prerogative state' in which the chairmanship of the party became the most important position of power in the country.

Economic Policies

As you learnt last year in your study of Marxism (Matu 8, Lesson 4), a good communist understands that historical progress is only made by socially organised development of the productive forces. The Marxist materialist base and superstucture analysis leads to the conclusion that political, social and cultural change can only be brought about by transforming the economic means of production. Lenin and Bukharin's New Economic Policy had been an essential but temporary 'capitalist' measure necessary to save the revolution. By 1928, the time was right for the next stage in the development of Communism in Russia. By turning on Bukharin and the NEP, Stalin introduced the First Five Year Plan of state centralised, forced industrialisation. As he famously said when justifying the programme:

As you learnt last year in your study of Marxism (Matu 8, Lesson 4), a good communist understands that historical progress is only made by socially organised development of the productive forces. The Marxist materialist base and superstucture analysis leads to the conclusion that political, social and cultural change can only be brought about by transforming the economic means of production. Lenin and Bukharin's New Economic Policy had been an essential but temporary 'capitalist' measure necessary to save the revolution. By 1928, the time was right for the next stage in the development of Communism in Russia. By turning on Bukharin and the NEP, Stalin introduced the First Five Year Plan of state centralised, forced industrialisation. As he famously said when justifying the programme:

Speech to Industrial Managers, February 1931.

It is sometimes asked whether it is not possible to slow down the tempo somewhat, to put a check on the movement. No, comrades, it is not possible! The tempo must not be reduced! On the contrary, we must increase it as much as is within our powers and possibilities. This is dictated to us by our obligations to the workers and peasants of the USSR. This is dictated to us by our obligations to the working class of the whole world.

To slacken the tempo would mean falling behind. And those who fall behind get beaten. But we do not want to be beaten. No, we refuse to be beaten!...

In the past we had no fatherland, nor could we have one. But now that we have overthrown capitalism and power is in our hands, in the hands of the people, we have a fatherland, and we will defend its independence. Do you want our socialist fatherland to be beaten and to lose its independence? If you do not want this you must put an end to its backwardness in the shortest possible time and develop genuine Bolshevik tempo in building up its socialist system of economy. There is no other way. That is why Lenin said on the eve of the October Revolution: "Either perish, or overtake and outstrip the advanced capitalist countries.

We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.

Source: J. V. Stalin, Problems of Leninism, (Moscow, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1953) pp. 454-458.

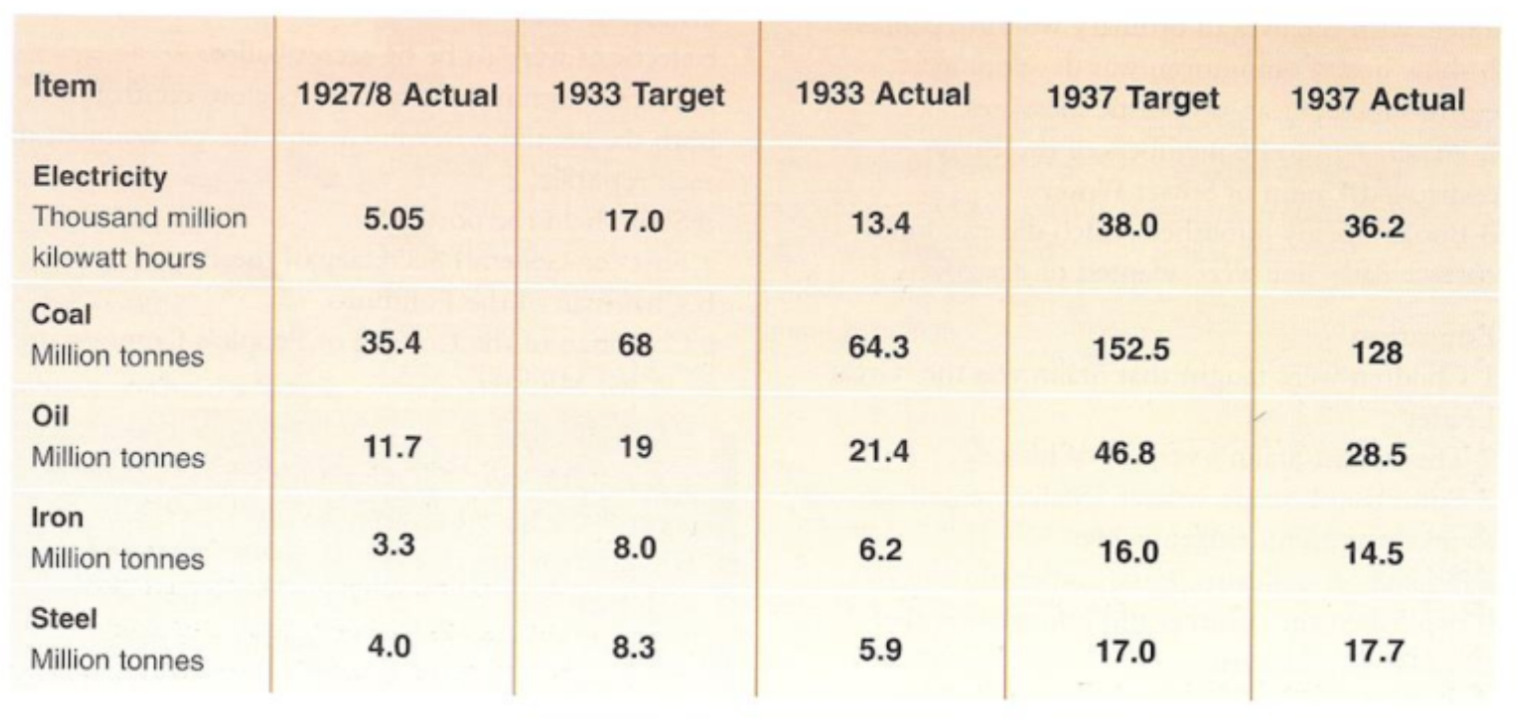

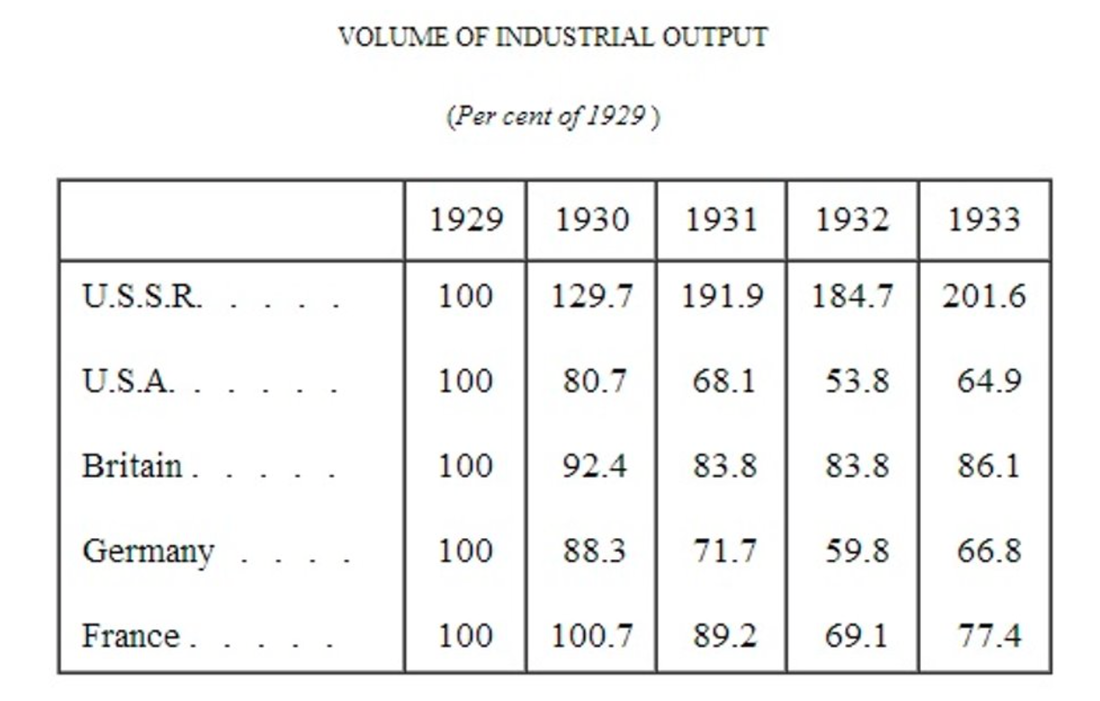

With the Five Year Plans, industrial production was controlled by the state and administered by Gosplan, a central planning agency. This was both an extension of Lenin's earlier War Commuism but also Stalin's interpretation of the Marxist goal that capitalism and capitalist should be abolished and replaced by socialised production. It was to the command economy, backed by the political dictatorship of the proletariat that would build communism, through rational and efficient centralised planning that would be both morally and economically superior to the inequality and 'boom and bust' anarchy of capitalist markets. And as a model for the modernisation of a backward, agrarian, largely peasant based economy there is little doubt that economically it worked. Significant production improvements were made across a range of industrial products including coal, electricity and iron. So that by the outbreak of the Second World War, the USSR was the world's second industrial power. At a time when the capitalist West had suffered the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression and a collapse of industrial production of 25-30%, the USSR had actully doubled its output. But...

,,, at what social cost. Central to the thinking behind the Five Year Plans was the acknowledgement that all industrial revolutions need to be backed by successful agricultural revolutions. (See the industrialisation of Britain Matu 4, Lesson 2) For Stalin and the planners, this was to be achieved by encouraging the Soviet peasantry to leave their private land and to join giant collective farms. The hope that the peasants would so this voluntarily was quickly abandoned. In 1930, Stalin dismantled the village mir (local town council) and replaced it with a kolkhoz administration who sent officials into the countryside to organise town meetings and pressure peasants to join collective farms. Any failures in collectivization was blamed on the Kulaks, successful farmers accused of hoarding grain. By 1932, 62% of land was collectivized and around 17 million peasants left their land to work in industry. Perhaps 5-6 million were exiled, many dying along the way or in harsh camps and settlements. The Ukraine famine is famous but losses among the Kazakhs of Central Asia were even more dramatic. Nomads herded into farms lost both their way of life and their animals. Still not satisfied with the speed of collectivisation, the state sent in requisitioning squads to seize all the peasants grain including the grain intended for planting. The consequence was famine on a scale not seen since the Middle Ages.

Both films below should be watched.

Both films below should be watched.

|

|

|

Social Policies

As with political and economic policy, Stalin's social policies were concerned with furthering the ideological goals of creating a Communist regime, and also with the more pragmatic concern of generating popular support for the regime. In 1924 there had been 472,000 Party members, by 1928 there were already 1.3 million.

As with political and economic policy, Stalin's social policies were concerned with furthering the ideological goals of creating a Communist regime, and also with the more pragmatic concern of generating popular support for the regime. In 1924 there had been 472,000 Party members, by 1928 there were already 1.3 million.

|

The new party members were young, uneducated workers and peasants, the ideological backbone of the Marxist state and ready to appreciate the material advantages of social mobility.

With the expansion of the state as a consequence of the Five-Year Plan membership stood at 3.5 million by 1934. The vast majority of these co-opted members had enjoyed significant social mobility and were ready to believe in the goal of socialism made realistic with the economic achievements of the Five-Year Plan. See the dramatic reconstruction of the experience of the American socialist John Scott in Magnitogorsk in the early 1930s. |

|

For the vast majority of the rest of population it was all about coming to terms with the new reality of a world in which the allocation of scarce resources depended on your ability to say and do the right thing at the right time. This is what we mean by passive consent. As my old teacher Neil Harding argued: 'In most times men are guided by a prudent concern for their own welfare and for that of those who are close to them'. So when the state is the guarantor of access to welfare provision, it is understandable that most people are unlikely to rebel.

1932-34 turning point.

Lenin had been responsible for introducing a number of social reforms that had long been the ambition of European socialists. Women's liberation, progressive education and radical anti- religious policy had characterised many of the key social policies of the period. But the period from 1932-3 saw a series of measures to reimpose discipline on citizens, including internal passports and draconian labour laws. After 1934 social policy in relation to women, the church and educaion became increasingly conservative.

1932-34 turning point.

Lenin had been responsible for introducing a number of social reforms that had long been the ambition of European socialists. Women's liberation, progressive education and radical anti- religious policy had characterised many of the key social policies of the period. But the period from 1932-3 saw a series of measures to reimpose discipline on citizens, including internal passports and draconian labour laws. After 1934 social policy in relation to women, the church and educaion became increasingly conservative.

(i) Women and families

As we have seen (Matu 8, Lesson 7) the Bolshevik approach to the women's question in the first years of the revolution under Lenin had been extraordinarily progressive for the time. The Bolsheviks issued decrees that promoted legal equality for women, they introduced civil marriage and made divorce easier to obtainand they encouraged women to enter the workforce and contribute to the Soviet economy. They established laws to promote equal pay for equal work and mandated maternity leave. Additionally, they initiated campaigns to eliminate illiteracy and increase educational opportunities for women. Under Stalin many of these achievements were reversed.

As we have seen (Matu 8, Lesson 7) the Bolshevik approach to the women's question in the first years of the revolution under Lenin had been extraordinarily progressive for the time. The Bolsheviks issued decrees that promoted legal equality for women, they introduced civil marriage and made divorce easier to obtainand they encouraged women to enter the workforce and contribute to the Soviet economy. They established laws to promote equal pay for equal work and mandated maternity leave. Additionally, they initiated campaigns to eliminate illiteracy and increase educational opportunities for women. Under Stalin many of these achievements were reversed.

|

After 1934 social policy became increasingly conservative. Alarmed by figures from Moscow showing divorce ending one in three marriages and 2.7 abortions for every birth, measures were taken to bolster the family. Homosexuality was recriminalised, abortion virtually banned and divorce made more difficult. Propaganda was used to promote a cult of motherhood. By 1944 Stalin was copying the fascism with his Order of Maternal Glory. It was conferred to women in three classes. First class: mothers bearing and raising nine children. Second class: mothers bearing and raising eight children. Third class: mothers bearing and raising seven children.

|

(ii) The Church

In the 1920s and early 1930s militants from the atheist 'League of the Godless' joined police actions against traditionalist peasants during collectivisation. Mosques were closed, icons smashed and priests exiled or killed. After 1934, whilst atheist propaganda continued, the pressure on religion subsided and around 45 per cent of the population remained believers. During the Second World War, orthodox Christianity would be promoted again as a symbol of national unity.

In the 1920s and early 1930s militants from the atheist 'League of the Godless' joined police actions against traditionalist peasants during collectivisation. Mosques were closed, icons smashed and priests exiled or killed. After 1934, whilst atheist propaganda continued, the pressure on religion subsided and around 45 per cent of the population remained believers. During the Second World War, orthodox Christianity would be promoted again as a symbol of national unity.

(iii) Education and indoctrination

The most effective way to build support for an authoritarian regime is not through coercion, but through gradually instilling the values of the regime in the young. Youth policies in Russia, as in other totalititarian states, were designed to produce adults who felt that Communist ideology was a normal, ‘common sense’ way of seeing the world. In the 1920s educationalists led by Anatoli Lunacharski campaigned against elitist, academic education. Others attempted 'de-schooling' and then 'learning through labour'. Universities and schools were disrupted. But from 1932 order and tradition was once again restored. The progressive methods and anti-academic campaigns of the late 1920s were replaced and homework, uniforms, exams and discipline returned. History, which had been considered irrelevant after the Revolution, was reinstated. Its role was to promote patriotism and knowledge of world events culminating in the victory of Soviet Communism. Schoolbooks were based on Stalin's single approved text: the 'Short Course'. Stalin's pamphlets on issues such as linguistics and politics could not be contradicted. Outside of school the Party operated youth organisations that served a similar function as the Fascist youth groups and Hitler Youth. The Soviet Young Pioneers catered for the young up to the age of 14 and then Komsomol until the age of 28. The Young Pioneers grew from a membership of about 75,000 in 1923, to nearly 14 million by 1940.

Despite the propaganda and state control over the curriculum, continued real progress was made in bringing literacy to virtually all adults, through evening schools, sending teachers to villages and building 70,000 libraries. In 1913 2.7 million newspapers had been sold in Russia by 1939 as many as 38 million were sold. Workers were educated as specialists and officials, while universities had produced one million graduates by 1940 - one-third of them in engineering. In 1927 most children attended school for four years; by 1940, most attended from 7 to 13 years.

The most effective way to build support for an authoritarian regime is not through coercion, but through gradually instilling the values of the regime in the young. Youth policies in Russia, as in other totalititarian states, were designed to produce adults who felt that Communist ideology was a normal, ‘common sense’ way of seeing the world. In the 1920s educationalists led by Anatoli Lunacharski campaigned against elitist, academic education. Others attempted 'de-schooling' and then 'learning through labour'. Universities and schools were disrupted. But from 1932 order and tradition was once again restored. The progressive methods and anti-academic campaigns of the late 1920s were replaced and homework, uniforms, exams and discipline returned. History, which had been considered irrelevant after the Revolution, was reinstated. Its role was to promote patriotism and knowledge of world events culminating in the victory of Soviet Communism. Schoolbooks were based on Stalin's single approved text: the 'Short Course'. Stalin's pamphlets on issues such as linguistics and politics could not be contradicted. Outside of school the Party operated youth organisations that served a similar function as the Fascist youth groups and Hitler Youth. The Soviet Young Pioneers catered for the young up to the age of 14 and then Komsomol until the age of 28. The Young Pioneers grew from a membership of about 75,000 in 1923, to nearly 14 million by 1940.

Despite the propaganda and state control over the curriculum, continued real progress was made in bringing literacy to virtually all adults, through evening schools, sending teachers to villages and building 70,000 libraries. In 1913 2.7 million newspapers had been sold in Russia by 1939 as many as 38 million were sold. Workers were educated as specialists and officials, while universities had produced one million graduates by 1940 - one-third of them in engineering. In 1927 most children attended school for four years; by 1940, most attended from 7 to 13 years.

Cultural Policies

"And therefore I raise my glass to you, writers, the engineers of the human soul"

(Joseph Stalin, "Speech at home of Maxim Gorky", 26 October 1932).

Stalin's state is to be considered a totalitarian regime because the cultural ambitions of the state extended beyond the ‘social depoliticization’ of censorship and propaganda to include state control of media and arts to promote a new sense of social being. The last time we saw this degree of ambition was during the final phase of the French Revolution and Robespierre's attempt to replace the cultural power of the Catholic Church with a cult of reason. (Matu 2 - Lesson 9) We have recently also seen how Hitler and Mussolini attempted to shape a sensibility that might be considered to be new ‘fascist man’, but this was a pale imitation compared to what was attempted in Stalin's Russia. Firstly, Stalin was able to draw upon an extraordinarily rich philosophical tradition of socialist thinkers who had speculated on how human nature would be transformed when avaricious capitalism was overthrown. The anti-intellectualism of fascism/Nazism meant there was no right wing equivalent. Secondly, because the Communist state was considerably more empowered through the command economy, it meant that the control and allocation of resources to cultural projects far exceded anything possible in fascist regimes.

"And therefore I raise my glass to you, writers, the engineers of the human soul"

(Joseph Stalin, "Speech at home of Maxim Gorky", 26 October 1932).

Stalin's state is to be considered a totalitarian regime because the cultural ambitions of the state extended beyond the ‘social depoliticization’ of censorship and propaganda to include state control of media and arts to promote a new sense of social being. The last time we saw this degree of ambition was during the final phase of the French Revolution and Robespierre's attempt to replace the cultural power of the Catholic Church with a cult of reason. (Matu 2 - Lesson 9) We have recently also seen how Hitler and Mussolini attempted to shape a sensibility that might be considered to be new ‘fascist man’, but this was a pale imitation compared to what was attempted in Stalin's Russia. Firstly, Stalin was able to draw upon an extraordinarily rich philosophical tradition of socialist thinkers who had speculated on how human nature would be transformed when avaricious capitalism was overthrown. The anti-intellectualism of fascism/Nazism meant there was no right wing equivalent. Secondly, because the Communist state was considerably more empowered through the command economy, it meant that the control and allocation of resources to cultural projects far exceded anything possible in fascist regimes.

|

Whereas the Nazi regime was clear about what cultural products it was opposed to (modernism or 'degenerate art'), only Stalinism was clear about the nature of its alternative, 'socialist realism'.

As we have seen, all authoritarian regimes embrace an aesthetic which emphasises the power of the state (see the excellent Jonathan Meades documentary ‘Ben Building'). But socialist realism went further in clearly enunciating not just a style but also a state sponsored narrative of working class and peasant socialist fables and morality tales, full of heroes and villains all based on a revolutionary foundation myth that genius director Sergei Eisenstein captured on screen (see right) and Orwell later satarised in Animal Farm. |

|

Just as we have seen with Soviet social policy - which was transformed from the radical, progressive policies under Lenin to the reactionary, conservative policies under Stalin - so also with Soviet culture and the arts. The early Bolshevik leaders had welcomed the avant garde, self-consciously modern Russian art which, like the revolution itself, seemed to be pointing a way to the future. But as the film below clearly explains, Stalin had no time for this art he considered to be elitist and too independent. 'Stalin would personally look at works read novels

watch plays so that he could give his stamp of approval or callous condemnation'. The Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP) was established in 1928 as a cultural dimension of the First Five Year plans. By 1932 if work was to be published it would be expected to follow the guiding principles of of socialist realism.

watch plays so that he could give his stamp of approval or callous condemnation'. The Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP) was established in 1928 as a cultural dimension of the First Five Year plans. By 1932 if work was to be published it would be expected to follow the guiding principles of of socialist realism.

|

|

Maxim Gorky's 1933 guidelines for socialist realism: 1. The work must be proletarian, i.e. art relevant to the workers and understandable to them. 2. The art should be typical and include scenes of everyday life of workers and peasants. 3. The art should be realistic in the representational sense. As Hitler had done it also dismissed abstract expressionist art. 4. The work should support the aims of the State and the Party, 'art for art's sake' was pointless, bourgeois and counter-revolutionary. The following are examples of the visual style of socialist realism: |

Very good examples of the message of socialist realism can be seen in the mythical status accorded to two heroes of the USSR, Pavlik Morozov and Alexei Stakhanov.

|

Pavlik Morozov was a Soviet youth hailed as a hero for his unwavering loyalty to the communist regime. Born in 1918, he reported his own father to Soviet authorities in 1932, accusing him of anti-communist sentiments. This act led to his father's execution, and Pavlik became a symbol of the Soviet state's influence over family loyalty. His story was promoted in Soviet propaganda, showcasing him as a model of devotion to the Communist Party. His story was a subject of songs, plays, a full-length opera, six biographies and in Bezhin Meadow, a film directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Morozov was murdered in 1932, likely by family members seeking revenge.

|

|

Alexei Stakhanov was a Soviet coal miner and a prominent figure in the early years of the Soviet Union. Stakhanov's claim to fame came on August 31, 1935, when he reportedly extracted 102 tons of coal in a single shift, significantly exceeding the standard quota for miners at the time. Stakhanov's feat was widely publicized by the Soviet government, which promoted him as a hero and a symbol of the success of the Soviet industrialization efforts. The Stakhanovite movement led to the development of "shock brigades" who were expected to exceed production targets significantly.

|

In line with the general development of the USSR in the 1930s, in the years preceding the World War Two control over the arts was intensified and artists fell victim to the purges. The great composer Shostakovich was targetted in 1936. Stalin had walked out of a performance and the party newspaper Pravda attacked his work. Shostakovich famously protected his family by sleeping in the corridor outside his appartment and kept a small ready packed suitcase by his front door for the moment when the NKVD came for him. His response was to produce his 5th symphony, subtitled 'A Soviet Artist's Response to Just Criticism' and in the approved ultra-nationalist style. It was triumph and he survived. Other artists would not be so lucky. For the 1936–37 theatre season: 10 of 19 plays were taken off major theatre stages, 56 plays were removed and banned. In 1935–37, 102 films were stopped in production and twenty already released were taken out of circulation.

Foreign Policies

Unlike the imperial expansionism which was central to the fascist and Nazi policy goals and the traditionalist Marxist goal of fomenting world revolution, Stalin's foreign policy was largely guided by his emphasis on "Socialism in One Country." He believed that the Soviet Union needed to focus on internal development and industrialization while consolidating socialism within its own borders. This inward-looking approach aimed to make the Soviet Union a self-reliant and powerful state. That said there were a number of Soviet foreign policy initiatives in the 1930s which had significant consequences.

The Communist International in the 1920s and early 1930s, under the influence of Stalin, believed that social democratic parties in Western Europe were traitors to the working class because they did not support a more radical, revolutionary agenda. The German Social Democratic Party (SPD), were considered to be 'social fascists' because they promised workers that capitalism could be refomed without the need for social revolution. They argued that social democrats were essentially serving the interests of capitalism and were complicit in preserving the capitalist system. Consequently, the Communist Parties of Europe were prevented from working with socialists to offer a united front against the rise of fascism. In contrast, Hitler was able work with the traditional right in German and was faced with a divided left wing opposition. The policy on social fascism was dropped in the later 1930s and allowed the Soviet Union to support the Spanish Republic in the Civil War from 1936 to 1939 but longstanding divisions within the left certainly weakened the war effort.

Unlike the imperial expansionism which was central to the fascist and Nazi policy goals and the traditionalist Marxist goal of fomenting world revolution, Stalin's foreign policy was largely guided by his emphasis on "Socialism in One Country." He believed that the Soviet Union needed to focus on internal development and industrialization while consolidating socialism within its own borders. This inward-looking approach aimed to make the Soviet Union a self-reliant and powerful state. That said there were a number of Soviet foreign policy initiatives in the 1930s which had significant consequences.

The Communist International in the 1920s and early 1930s, under the influence of Stalin, believed that social democratic parties in Western Europe were traitors to the working class because they did not support a more radical, revolutionary agenda. The German Social Democratic Party (SPD), were considered to be 'social fascists' because they promised workers that capitalism could be refomed without the need for social revolution. They argued that social democrats were essentially serving the interests of capitalism and were complicit in preserving the capitalist system. Consequently, the Communist Parties of Europe were prevented from working with socialists to offer a united front against the rise of fascism. In contrast, Hitler was able work with the traditional right in German and was faced with a divided left wing opposition. The policy on social fascism was dropped in the later 1930s and allowed the Soviet Union to support the Spanish Republic in the Civil War from 1936 to 1939 but longstanding divisions within the left certainly weakened the war effort.

|

As the USSR became increasinly concerned about the rise of German militarism in the 1930s Stalin, made efforts to build alliances with Western countries, particularly France and the United Kingdom. The goal was to create a system of collective security to deter potential aggression. This culminated in the Soviet Union's participation in the League of Nations in 1934, seeking to counter the increasing militarization and expansionist policies of Nazi Germany and Japan. But failure to reach a defensive pact with Britain in 1939 led to a dramatic turn when the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (also known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact) with Nazi Germany. This pact included a secret protocol that divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, effectively allowing the Soviet Union to annex territories in the Baltic states and parts of Poland.

|

Activity

The activity for this lesson will be a class based essay. Make sure to put your notes - supplemented from here if necessary - in your OneNote.

The activity for this lesson will be a class based essay. Make sure to put your notes - supplemented from here if necessary - in your OneNote.

Extension and extras (essential for IB students.)

Your textbook is fine on the economic aspects of the Five-Year Plans and collectivisation. It also covers some of the social consequences. Apart from the 'cult of Stalin', it has nothing much to say about the cultural policies. You can, however, get an excellent overview with great examples from this textbook - Peter Oxley, Russia 1855-1991, From Tsars to Commissars.

Summary sheet taken from James Mason Modern World history to GCSE.

Jim Grant on who won and lost in Stalin's Russia.

JDC on the social consequences of Stalin's policies and on Collectivisation and Five Year Plan

One of the best illustrations of the complex, sometimes contradictory nature of Stalin's policies is the story of the town on Magnitogorsk as told by the American communist who worked there, John Scott. The film 'Life in Stalin's Russia' a BBC schools production is based on Scott's book Behind the Urals. This worksheet produced for my European School students a few years ago contains some interesting extracts from the book.

See also striking images and video from 17 moments in Soviet History website - Magnetic mountain.

John D Clare - www.johndclare.net/Russ1.htm

Spartacus - spartacus-educational.com/RussiaSU.htm

My films below provide you with a generic, conceptual overview of how consent can be manufactured in authoritarian states. My pages on the IB section of the site also provide you with more details.

Your textbook is fine on the economic aspects of the Five-Year Plans and collectivisation. It also covers some of the social consequences. Apart from the 'cult of Stalin', it has nothing much to say about the cultural policies. You can, however, get an excellent overview with great examples from this textbook - Peter Oxley, Russia 1855-1991, From Tsars to Commissars.

Summary sheet taken from James Mason Modern World history to GCSE.

Jim Grant on who won and lost in Stalin's Russia.

JDC on the social consequences of Stalin's policies and on Collectivisation and Five Year Plan

One of the best illustrations of the complex, sometimes contradictory nature of Stalin's policies is the story of the town on Magnitogorsk as told by the American communist who worked there, John Scott. The film 'Life in Stalin's Russia' a BBC schools production is based on Scott's book Behind the Urals. This worksheet produced for my European School students a few years ago contains some interesting extracts from the book.

See also striking images and video from 17 moments in Soviet History website - Magnetic mountain.

John D Clare - www.johndclare.net/Russ1.htm

Spartacus - spartacus-educational.com/RussiaSU.htm

My films below provide you with a generic, conceptual overview of how consent can be manufactured in authoritarian states. My pages on the IB section of the site also provide you with more details.

|

|

|