Lesson 2 - Three case studies in decolonisation: India (negotiated), Indo-China (violent) and the Congo (accelerated).

|

|

Before looking at the three case studies, it is worth watching this excellent overview from the People's Century series which broadens the examples and provides an overview in one 50 minute sweep.

(Password - moser) The article that goes with it is also very good. |

India (negotiated decolonisation)

Internal Factors influencing the movement towards Indian Independence:

External factors influencing the movement towards Indian Independence

- Educated leadership: Britain encouraged Western-style education, which developed an educated middle class who became the leaders of India. Indian leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru were educated as lawyers in England.

- Indian nationalism: Indian nationalism (the desire to have an independent India) had been growing since the 19th century.

- The development of technology - the railways, the postal system - and the spread of the English language created greater unity in India than ever before.

- The Indian Congress Party was the main party which wanted an independent India.

- Gandhi became the leader of the Indian independence movement between the First and Second World Wars. His tactics of peaceful resistance increased discontent against the British. The British government reacted to this by giving more power to India. Under the Government of India Act 1935, India had a national assembly and assemblies in the provinces under the control of the Governor-General. 1945 election: After the war, the Labour Party, led by Clement Attlee, took over government in Britain.

- The Labour Party supported a rapid move to Indian independence.

External factors influencing the movement towards Indian Independence

- World War II - Indian leaders took advantage of Britain's involvement in the war by increasing their campaign for independence. The advance of the Japanese through Burma forced the British to send Sir Stafford Cripps to India to discuss the process of independence with Indian leaders. Indian leaders were also more involved in ruling their country. The experience of World War II encouraged Indian nationalist leaders to continue the campaign for full independence.

- After the war, Britain was financially exhausted, owed £3.5 billion and was dependent on the US for loans, and the US was opposed to British control of India. The country was bankrupt, many of its cities were in ruins, its exports fell and the pound sterling was weak. It could not afford to maintain its empire.

|

On 3 June 1947, in New Delhi, Lord Mountbatten and the main leaders of India negotiate the partition of that country in accordance with the British plan. From left to right: Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Vice-President of the Interim Government; Lord Hastings Ismay, adviser to Lord Mountbatten; Lord Louis Mountbatten, Viceroy of India; and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, ‘Great Leader’ of the All-India Muslim League

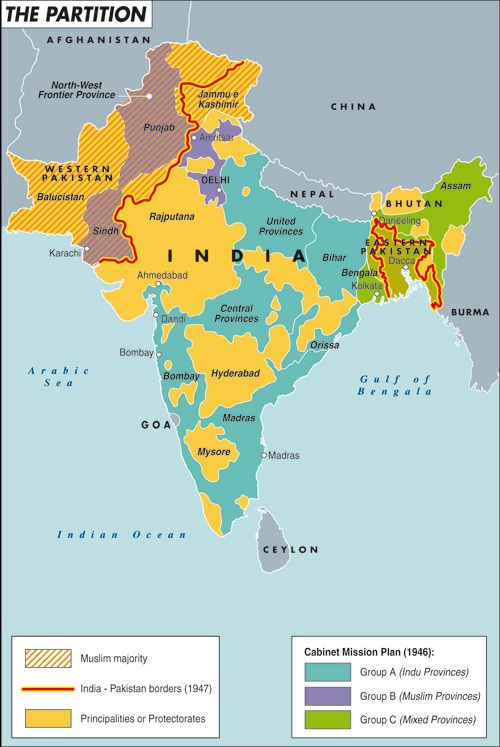

Lord Mountbatten was given responsibility for negotiating the transfer of power. India was to be partitioned. It proposed that power would be handed over to two governments, one in India and one in Pakistan. They would have dominion status within the Commonwealth and would operate like that until they drew up their own constitutions. This plan meant that India would have to be partitioned between a majority Hindu country and a majority Muslim country. However, the distribution of the Muslim population presented problems. They were concentrated in the north-west and north-east of India and others were scattered throughout the country.

|

The new governments took over on 15 August 1947 and British forces began to withdraw. Nehru became Prime Minister of India, while Ali Khan became Prime Minister of Pakistan. The British withdrawal had avoided a civil war, but as Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs moved home, hundreds of thousands were massacred. India was the largest country to be decolonised and it became the largest democracy in the world. Relations between India and Pakistan were strained - they fought three wars over Kashmir. India was Britain's largest overseas possession. Once India got its independence, the reasons for holding onto the rest were weakened. Soon after, Ceylon, Burma and Malaya got their independence. India and Pakistan remained part of the British Commonwealth.

|

|

|

Indo-China (violent decolonisation)

The decolonisation of Indo-China was the longest and most violent example of all. Although French decolonisation of Indo-China was complete by 1956, the logic of the Cold War saw the Americans remain in conflict with the North Vietnamese until 1973. And not until 1975 was a united Vietnam, finally realised.

Internal Factors

External Factors

The 'Bao Dai Solution'

In 1948, Vietnam under Bao Dai was accepted as a state within the French Union. The next year, the independence of Vietnam under his leadership was recognised by the French Government, but no vote of the people of the newly independent state was taken. This proved no solution to the war against the Vietminh. However, it did provide the French with a pretence for remaining in Indo-China. Bao Dai's regime was presented as an independent state under attack from communism. Once China installed a communist regime (1949), the domino theory was advanced as a justification for staying. If Indo-China fell to communism too, then who would be next? A war that had begun in 1946 over French imperialism had, in three years, mushroomed into part of a regional struggle against communism in South East Asia. The United States backed the French to the hilt because they assumed that the Vietminh and even the Chinese communists were puppets of the USSR.

The defeat of France: General Giap and Dien Bien Phu, 1950-54

It is probable that no single, individual influenced the outcome of the wars in Indo-China more than General Vo Nguyen Giap. [Died in 2013 aged 102] In the fighting against the French between 1946 and 1949, Giap masterminded the guerrilla tactics that frustrated the French. Well-armed by the Chinese from 1950, however, he switched to a modern war of movement. The French were forced to 'Vietnamise' their armed forces by raising an army from Bao Dai's supporters. The war also became 'Americanised' in that the USA supplied $2,900 million of aid in 1950-54, and in the last year were bearing 80 per cent of the cost.

Internal Factors

- A key concept of French imperialism, known as 'assimilation', perceived colonies as one and indivisible from France. In the official mind, France had no colonies, only departments. This created a 'them and us' culture which excluded the colonised from power and left little room for compromise and negotiation.

- The Indo-Chinese were worked and taxed hard; there had been a tax strike against the French as early as 1907.

- The First World War ended with French promises of reform to the Indo-Chinese who had fought with them. But, as in North Africa, the white settler class resisted. Therefore, co-operation, turned into opposition.

- 1927 the National Party of Vietnam was founded, determined to end French rule altogether. Its leader was Ho Chi Minh, a communist who thought his homeland was not yet ready for communism.

- The Indo-Chinese economy had been turned into one of cash crops for export. As rice and rubber flowed out of the country, peasants found it increasingly impossible to support a growing population.

- The Vietminh (national independence coalition formed Hồ Chí Minh in May 1941) did not pursuing a strict communist policy of land expropriation during WWII and it had even retained the support of landlords. In the towns, it was well supported by the middle class, to whose nationalist sentiments it appealed.

- After World War II de Gaulle and France wanted to rebuild her empire. (Contrast to UK in India) Cambodian and Laotian monarchies were restored.

- The French imposed Bao Dai as their puppet to be their leader of Vietnam. Bao Dai's had a history of collaboration with both the French and Japanese.

External Factors

- The Japanese took advantage of French defeat in 1940. The colonial Vichy regime, under Admiral Decoux, signed a compromise agreement by which the Japanese were allowed into the northern areas which was very unpopular and helped provoke nationalist sentiment.

- In March 1945, Japan launched a full-scale invasion to support their failing war campaign in the Far East. They installed the Emperor Bao Dai as a puppet ruler, but he was overthrown by the nationalist coalition of the Vietminh.

- The United States, despite supporting the Vietminh’s wartime struggle against the Japanese, decided not to oppose French recolonisation because of the new Cold War fear of the spread of communism.

- The 'August revolution' in 1945 declared the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The French refused to recognise it, and from October 1945 the longest war of decolonisation of the twentieth century began. The colonial war against the French was a prelude to that against the world's strongest power, the United States. There is no better example of the continuity between decolonisation and Cold War conflicts.

The 'Bao Dai Solution'

In 1948, Vietnam under Bao Dai was accepted as a state within the French Union. The next year, the independence of Vietnam under his leadership was recognised by the French Government, but no vote of the people of the newly independent state was taken. This proved no solution to the war against the Vietminh. However, it did provide the French with a pretence for remaining in Indo-China. Bao Dai's regime was presented as an independent state under attack from communism. Once China installed a communist regime (1949), the domino theory was advanced as a justification for staying. If Indo-China fell to communism too, then who would be next? A war that had begun in 1946 over French imperialism had, in three years, mushroomed into part of a regional struggle against communism in South East Asia. The United States backed the French to the hilt because they assumed that the Vietminh and even the Chinese communists were puppets of the USSR.

The defeat of France: General Giap and Dien Bien Phu, 1950-54

It is probable that no single, individual influenced the outcome of the wars in Indo-China more than General Vo Nguyen Giap. [Died in 2013 aged 102] In the fighting against the French between 1946 and 1949, Giap masterminded the guerrilla tactics that frustrated the French. Well-armed by the Chinese from 1950, however, he switched to a modern war of movement. The French were forced to 'Vietnamise' their armed forces by raising an army from Bao Dai's supporters. The war also became 'Americanised' in that the USA supplied $2,900 million of aid in 1950-54, and in the last year were bearing 80 per cent of the cost.

|

In early 1954 a large army of 12,000 troops under General Henri Navarre got themselves surrounded in the long valley of Dien Bien Phu, in the north of Tonkin province. For almost two months the Vietminh bombarded with heavy artillery a French army unable to be relieved because its airstrips had been cut off. President Eisenhower was prepared to respond to French appeals to send in B-29 bombers from the Philippines bases, but Congress refused support. Consequently, 2,000 French died, and 10,000 were captured.

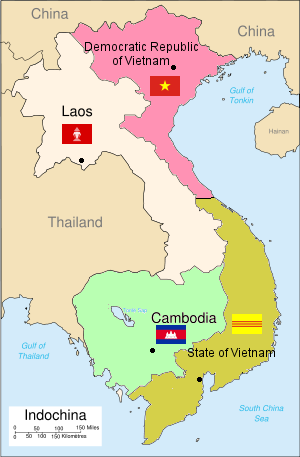

The Geneva Conference (1954) As in India, the Geneva agreement partitioned Vietnam into two separate states either side of the 17th parallel. Laos and Cambodia also became independent states. Therefore, it was not a permanent settlement, for the new government of North Vietnam regarded the South as still under imperialist domination. French masters had merely been exchanged for American ones. The United States never signed the settlement but agreed to abide by it. The promise of free elections for the whole of Vietnam by 1956 was not honoured because Secretary of State John Foster Dulles feared the Vietminh would win them. Instead, Bao Dai headed a compliant government in the South with Ngo Dinh Diem as Prime Minister. (The story continues in Cold War - Vietnam.) |

|

|

|

The Congo (accelerated decolonisation)

One of the features of accelerated decolonisation was that there appeared to be little pressure of decolonisation until it happened. But when it did happen, it happened very quickly. External factors (UNO, Cold War, foreign intelligence agencies) were critical to understanding how the process of decolonisation unfolded (badly!).

Unlike the Dutch in Indonesia, Belgian decolonisation did not appear imminent as the Second World War ended. The Congo had not suffered occupation, and in 1945 seemed to be one of the most stable examples of colonialism.

Unlike the Dutch in Indonesia, Belgian decolonisation did not appear imminent as the Second World War ended. The Congo had not suffered occupation, and in 1945 seemed to be one of the most stable examples of colonialism.

|

Internal Factors

|

- African advancement met with obstruction from white settlers who clung to the land, as they did in Kenya and Angola. Frustrated peasants migrated to the towns, adding to a growing surplus of unskilled labour.

- In the late 1950s, political organizations advocating for Congolese independence began to emerge. One of the most prominent was the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), founded by figures such as Patrice Lumumba, Cyrille Adoula, and Joseph Ileo.

- The first local government elections were held in 1957 and resulted in a majority for the Abako party (Alliance des Bakongo). Under Joseph Kasavubu's leadership it modernised its programme to advocate equal access to education and the administration.

External Factors

- World War Two stimulated the Belgian Congo economically, through increasing demand for its raw materials. Some Congolese resources became more valuable in the context of wartime shortages, leading to increased demand for products like rubber and minerals. Unlike Belgium itself the Congo remained un-invaded throughout the war. The Belgian government-in-exile, based in London, maintained some level of control over the colony, but local administrators in the Congo were given more autonomy in governing the territory.

- The social consequences of this industrialisation and economic growth - one-quarter of the population living in urban areas - resulted in Congolese workers beginning to behave like Belgian ones.

- Algerian War (1954-1962) The brutal and protracted nature of the Algerian War had a profound effect on Belgian policymakers. The number of French military personnel killed estimated to be between 25,000 and 30,000 + 1000s French civilians. 1m Algerians? A cautionary tale about maintaining colonial rule through force + international condemnation of French actions in Algeria influenced Belgian thinking.

- Bandung Conference (1955), brought together leaders from newly independent Asian and African countries and inspired nationalist movements across the continent.

- Suez Crisis (1957) Highlighted the declining power and influence of European colonial powers, including Britain and France. Belgium took note of the diplomatic and military failure of the Suez intervention and USA hostility which further underscored the inevitability of decolonization.

Economic problems and riots: accelerated decolonisation, 1959-60

The catalyst of Belgian decolonisation was the Leopoldville riots of January 1959. The first wave of industrialisation was over by 1955 and Congolese mineral exports fell from 1957 causing rising urban unemployment. The scale of the spontaneous violence in Leopoldville shocked the government of Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens (Prime Minister 1958 to March 1961.) The Belgians did not want suffer what the French were experiencing in Algeria. Negotiations began between the Belgian government and nationalist leaders at the Round Table Conference in Brussels in 1960. The Belgians wanted a gradual transfer of power over four years, but the Congolese leaders wanted immediate independence. Belgium gave in and agreed that elections would be held in May. On 30 June 1960, King Baudouin I of Belgium handed over power to the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in a ceremony in Leopoldville. The Congolese President was Joseph Kasavubu and the Prime Minister was Patrice Lumumba. In his speech, King Baudouin insulted the Congolese by praising the genius and courage of his uncle, Leopold II. In response, Lumumba criticised the Belgian government's 'regime of injustice, oppression and exploitation'. He said, 'We are no longer your monkeys.'

The catalyst of Belgian decolonisation was the Leopoldville riots of January 1959. The first wave of industrialisation was over by 1955 and Congolese mineral exports fell from 1957 causing rising urban unemployment. The scale of the spontaneous violence in Leopoldville shocked the government of Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens (Prime Minister 1958 to March 1961.) The Belgians did not want suffer what the French were experiencing in Algeria. Negotiations began between the Belgian government and nationalist leaders at the Round Table Conference in Brussels in 1960. The Belgians wanted a gradual transfer of power over four years, but the Congolese leaders wanted immediate independence. Belgium gave in and agreed that elections would be held in May. On 30 June 1960, King Baudouin I of Belgium handed over power to the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in a ceremony in Leopoldville. The Congolese President was Joseph Kasavubu and the Prime Minister was Patrice Lumumba. In his speech, King Baudouin insulted the Congolese by praising the genius and courage of his uncle, Leopold II. In response, Lumumba criticised the Belgian government's 'regime of injustice, oppression and exploitation'. He said, 'We are no longer your monkeys.'

"We have known ironies, insults, blows that we endured morning, noon, and evening, because we are Negroes. Who will forget that to a black man it is forbidden to walk in the street of certain towns in this country? Who will forget that a black man is addressed as 'tu,' not because he is a friend, but because the more a black man is humiliated, the more he is considered a Negro?"

Civil War in the context of the Cold War

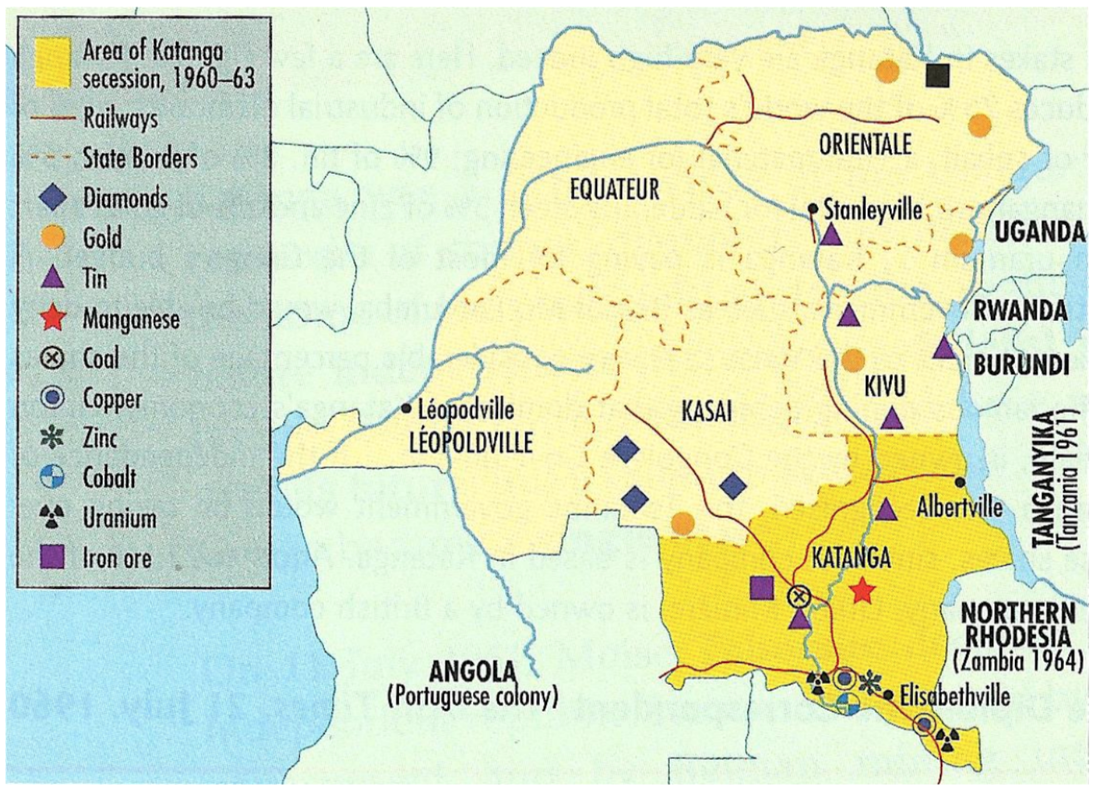

Independence began badly. Within days, there was a rebellion in the Congolese army as native soldiers rebelled against their white Belgian officers. The Belgian government flew in thousands of troops to protect white civilians and to take over many key positions. Lumumba declared that Belgium was at war with the Congo. The new state of the Congo faced further trouble when one of its riches provinces, Katanga, secretly encouraged by Belgium rebelled and declared its independence. Lumumba appealed to the United Nations. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 143, which called on Belgium to remove its troops. Lumumba demanded that UN troops end the secession of Katanga. Instead, the UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold, said the UN wanted to negotiate a settlement with Katanga. Hammarskjold died in mysterious circumstances. (This is currently under investigation at the UN) Lumumba asked the Soviet Union (USSR) for help. The US feared that the Congo would become a base for Soviet Communist operations in central Africa. At this point, US President Eisenhower authorised the CIA to assassinate Lumumba.

Independence began badly. Within days, there was a rebellion in the Congolese army as native soldiers rebelled against their white Belgian officers. The Belgian government flew in thousands of troops to protect white civilians and to take over many key positions. Lumumba declared that Belgium was at war with the Congo. The new state of the Congo faced further trouble when one of its riches provinces, Katanga, secretly encouraged by Belgium rebelled and declared its independence. Lumumba appealed to the United Nations. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 143, which called on Belgium to remove its troops. Lumumba demanded that UN troops end the secession of Katanga. Instead, the UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold, said the UN wanted to negotiate a settlement with Katanga. Hammarskjold died in mysterious circumstances. (This is currently under investigation at the UN) Lumumba asked the Soviet Union (USSR) for help. The US feared that the Congo would become a base for Soviet Communist operations in central Africa. At this point, US President Eisenhower authorised the CIA to assassinate Lumumba.

|

|

|

The Belgian government also planned to get rid of Lumumba because he was as an obstacle to their plans in the country. The President of the Congo, Kasavubu, dismissed Lumumba as Prime Minister of the Congo.

|

In turn, Lumumba accused Kasavubu of treason and dismissed him as President of the Congo. By now (September I960), the Congo was badly split between rival groups. On 14 September, with the support of the US and Belgium, Mobutu took over power in the Congo and expelled Russian advisers. Lumumba and two others were shot after being tortured. The Belgian media conspired to cover-up Belgium's involvement. (see Prezi opposite) Only very recently have things begun to change. BBC summer 2022 'Patrice Lumumba: DR Congo buries tooth of independence hero'.

It was the beginning of one of the most extra-ordinary authoritarian dictatorships of the 20th century. Despite the catastrophic abuses of power, Mobutu's anti-communism in Congo (Zaire) kept him in power until the end of the Cold War. (See next lesson) |

|

Activity

Download and complete this summary document on the three case studies of decolonisation. Below are two videos from John Green for those who feel they can't learn history unless Mr Green is teaching it. They were made nearly a decade apart - before and after fame and fortune - which explains the differences between them. The third film is a lecture from a series about colonisation and decolonisation that I first mentioned last year. Richard Evans is one of Britain's most important contemporary historians.

|

|

|

|