YouTube, history teaching and Hitler.

|

Until the summer of 2019 I ran a popular history channel on YouTube with more than 15,000 subscribers. When YouTube decided to clamp down on hate speech and other unpleasant nonsense that the internet had enabled, a number of innocent history teachers were shut down for sharing videos of 1930s fascism, I was one of them.

The story spread on Twitter and was quickly picked up by the Guardian newspaper in London and then spread around the world. As a result of this pressure, within days YouTube reinstated my videos and I assumed this would be the end of the story. Then a few weeks later, I received an email from YouTube to say the videos had been taken down again. Later that day, with no explanation, my account was deleted completely. I wrote to YouTube on a number of occasions but received no reply. The Guardian newspaper were very sympathetic and asked me to write a short account which they accepted for publication. The day it was due to run, another news story broke that needed an opinion piece and my story was dropped. (Below) |

For the Guardian - Unpubished article August 2019.

My love/hate relationship with YouTube

I love YouTube but recently our relationship has become a bit strained. I am a history teacher and run a YouTube channel of history videos that I use in my teaching. At the end of the summer term, YouTube deleted a couple of videos that I had uploaded, identifying them as ‘glorifying or inciting violence against another person or group of people’.

My love/hate relationship with YouTube

I love YouTube but recently our relationship has become a bit strained. I am a history teacher and run a YouTube channel of history videos that I use in my teaching. At the end of the summer term, YouTube deleted a couple of videos that I had uploaded, identifying them as ‘glorifying or inciting violence against another person or group of people’.

Both videos were BBC documentaries digitised from an old VHS cassette. Targeted at GCSE and earlier age groups, they dealt with the rise to power of Hitler in the 1930s. The content was a fairly standard account, typically the one used dramatic reconstruction to bring alive the accounts of those who lived through the period. The other, like most of the content of my channel, was an edited extract from a longer documentary, the relevant moments that allow me to illustrate a particular point in a lesson. Both were embedded on my website, along with the other lesson materials, to make it easy for me to find and for the students to review whenever they wanted.

Of course, a mistake must have been made. I was an innocent victim of YouTube’s recent, highly laudable decision of early June to no longer host ‘content promoting fascism, supremacism or Holocaust denial’. (Guardian June 2019) But I was not alone. My fellow history teacher Scott Alsopp actually had his whole channel removed the same day. A highly distraught Mr Alsopp took to the Twittersphere to publicise this injustice and fortunately the Guardian picked up on the story. His channel and my videos were restored within 24 hours of our highly publicised appeal. I assumed this would be the end of the story. YouTube would tweak its overly zealous algorithm and the long summer holiday could begin.

Of course, a mistake must have been made. I was an innocent victim of YouTube’s recent, highly laudable decision of early June to no longer host ‘content promoting fascism, supremacism or Holocaust denial’. (Guardian June 2019) But I was not alone. My fellow history teacher Scott Alsopp actually had his whole channel removed the same day. A highly distraught Mr Alsopp took to the Twittersphere to publicise this injustice and fortunately the Guardian picked up on the story. His channel and my videos were restored within 24 hours of our highly publicised appeal. I assumed this would be the end of the story. YouTube would tweak its overly zealous algorithm and the long summer holiday could begin.

|

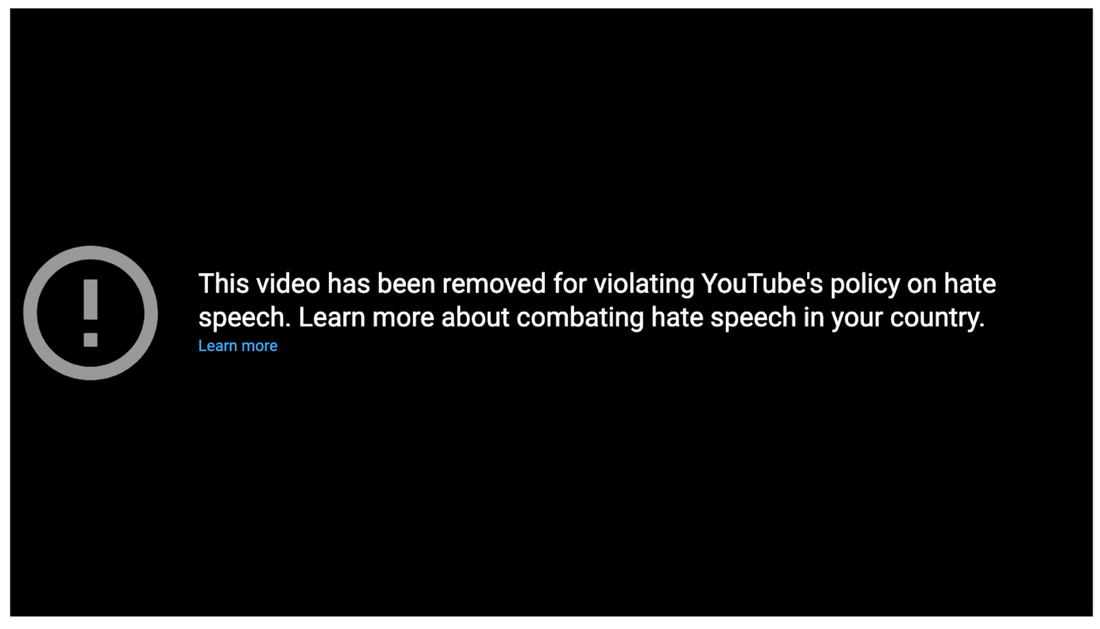

I was sitting by the hotel pool one morning a couple of weeks later, when I received notification from YouTube that they had removed the same offensive BBC schools docudrama a second time. Where my video had been, was a black screen with the words ‘This video has been removed for violating YouTube’s policy on hate speech’.

It got worse. By mid afternoon, my whole channel had been removed for ‘repeated or severe violations’ of YouTube’s anti-hate speech policy. You must remember that I am a history teacher. I justify my whole existence by doing the very opposite of what YouTube was now accusing me of. |

The week after, the Guardian published a long interview with YouTube’s Susan Wojcicki. She spoke very proudly of how the company uses ‘machines’ to remove content, 75% of the time before the video has had a single view. Is it really possible to delete enough?, she was challenged. “Yes, I think it is,” she said. “I’ve seen the progress we’ve made and I believe we will continue to make more progress.”

Staring at my screen where my YouTube account used to be, I found her words chilling.

Staring at my screen where my YouTube account used to be, I found her words chilling.

YouTube has always deleted my videos. If a video extract is too long to justify educational ‘fair use’ or if the copyright owner isn’t content to make money by placing their adverts on ‘my’ video, they can have it removed. I have played a friendly game of cat and mouse over the years with YouTube’s increasingly sophisticated algorithms. I get away with what I can and appeal to the educational goodwill of copyright holders when I have to. It usually works. An extended clip of Jacob Bronowski’s brilliant explanation of the Bronze Age in his Ascent of Man or my hour-long ‘history teacher’s edit’ of Adam Curtis’ Bitter Lake were amongst my notable appeal successes.

But what YouTube are doing now is clearly very different. Although ‘fair use’ and ‘educational use’ are not easily defined, they did provide something objective to appeal about. And although copyright ownership of an edited extract of a documentary film is not always clear, it did provide someone to appeal to. Previously, through the whole process, YouTube was merely the conduit; the host of arbitration discussions and the enforcer of a decision made elsewhere. Now, as Susan Wojcicki’s chilling words make clear, it is ‘we’, YouTube and their machines who will be doing the censoring. The standard YouTube statement reads 'we review educational, documentary, artistic, and scientific content on a case-by-case basis.' But who are the 'we'? Who ultimately controls what can and cannot be published on YouTube?

Should we just accept Susan Wojcicki’s perspective that YouTube can be trusted to control what can and cannot be seen. Are we happy to let algorithms routinely censor human creative content. If YouTube removes a video, I feel I should receive an email from an identifiable human, an individual who can explain why. I would also like an appeals process in place that independently decides whether a video should be published or not.

For this to happen, YouTube will need the support of its users. YouTube could create trusted communities of users, with moderators who self-police their content. YouTube could enhance their process of authentication. At the moment, YouTube users face initial restrictions on what they can do until they are ‘verified’. For example, I wouldn’t mind being asked to prove that I’m a teacher before I am allowed to claim my videos are ‘educational’. It would also be helpful if we targeted the commentators rather than the channels. How often do we take time to flag a comment as ‘inappropriate’? Every user who comments on YouTube is monitored. If they continually break community guidelines their account is deleted. It may be controversial, but YouTube could make the channels responsible for the comments of its users. When a channel uploads a video they can opt to disable comments or they can decide to pre-moderate them. Ten years ago, I used to allow right-wing extremists to post unpleasant comments, because I wanted to demonstrate to my history students that fascists still existed. Unfortunately, I have no need to prove the historical relevance anymore.

As you can imagine, losing 600+ videos and 10 years of teaching resources is quite a blow. My teaching website has many hundreds of pages with my videos embedded from YouTube. In place of those videos, it now says that my account has been ‘terminated’. How am I expected to explain this to my pupils, their parents and my school management? I have appealed again to the anonymous email address on the YouTube site, but two weeks have passed and the new term is fast approaching. I am sure YouTube will recognise their mistake again, I am sure my channel will be reinstated, but other than by writing a long letter of protest ‘for publication’ to the Guardian what else can I do?

Richard Jones-Nerzic - August 2019

But what YouTube are doing now is clearly very different. Although ‘fair use’ and ‘educational use’ are not easily defined, they did provide something objective to appeal about. And although copyright ownership of an edited extract of a documentary film is not always clear, it did provide someone to appeal to. Previously, through the whole process, YouTube was merely the conduit; the host of arbitration discussions and the enforcer of a decision made elsewhere. Now, as Susan Wojcicki’s chilling words make clear, it is ‘we’, YouTube and their machines who will be doing the censoring. The standard YouTube statement reads 'we review educational, documentary, artistic, and scientific content on a case-by-case basis.' But who are the 'we'? Who ultimately controls what can and cannot be published on YouTube?

Should we just accept Susan Wojcicki’s perspective that YouTube can be trusted to control what can and cannot be seen. Are we happy to let algorithms routinely censor human creative content. If YouTube removes a video, I feel I should receive an email from an identifiable human, an individual who can explain why. I would also like an appeals process in place that independently decides whether a video should be published or not.

For this to happen, YouTube will need the support of its users. YouTube could create trusted communities of users, with moderators who self-police their content. YouTube could enhance their process of authentication. At the moment, YouTube users face initial restrictions on what they can do until they are ‘verified’. For example, I wouldn’t mind being asked to prove that I’m a teacher before I am allowed to claim my videos are ‘educational’. It would also be helpful if we targeted the commentators rather than the channels. How often do we take time to flag a comment as ‘inappropriate’? Every user who comments on YouTube is monitored. If they continually break community guidelines their account is deleted. It may be controversial, but YouTube could make the channels responsible for the comments of its users. When a channel uploads a video they can opt to disable comments or they can decide to pre-moderate them. Ten years ago, I used to allow right-wing extremists to post unpleasant comments, because I wanted to demonstrate to my history students that fascists still existed. Unfortunately, I have no need to prove the historical relevance anymore.

As you can imagine, losing 600+ videos and 10 years of teaching resources is quite a blow. My teaching website has many hundreds of pages with my videos embedded from YouTube. In place of those videos, it now says that my account has been ‘terminated’. How am I expected to explain this to my pupils, their parents and my school management? I have appealed again to the anonymous email address on the YouTube site, but two weeks have passed and the new term is fast approaching. I am sure YouTube will recognise their mistake again, I am sure my channel will be reinstated, but other than by writing a long letter of protest ‘for publication’ to the Guardian what else can I do?

Richard Jones-Nerzic - August 2019

Addendum April 2023 - With no indication that they were about to do so, my YouTube account was reactivated in March 2023.

Addendum April 2024 - Much of what happened to me now makes sense in the light of Jamie Bartlett and Caitlin Smith's brilliant BBC Radio 4 podcast The Gatekeepers.

Addendum April 2024 - Much of what happened to me now makes sense in the light of Jamie Bartlett and Caitlin Smith's brilliant BBC Radio 4 podcast The Gatekeepers.